Restless sleep is commonly attributed to modern-day sedentary lifestyles, mobile phones, and electric lighting, however, according to a study conducted by Assistant Professor of Anthropology at UTM David Samson, it may actually be linked to ancient survival methods used by humans for nocturnal threat protection.

Samson conducted a study that showed how anxious sleeping habits in humans may be linked to the sentinel hypothesis. This hypothesis, originally proposed by Frederick Snyder in 1966, postulates that group-living species use a defence mechanism involving a few individuals staying awake and alert during the night while the majority of the group is asleep and vulnerable.

Samson and the study’s co-authors claim that sleeping in mixed-age groups has evolutionary benefits, as the different sleeping schedules of older and younger individuals allows for a few members of the group to be awake and vigilant while the others rest. Charlie Nunn, a co-author and Professor of Evolutionary Anthropology at Duke University, links these lighter sleep patterns to the ability to better defend oneself in the presence of a threat.

The study examined the Hadza tribe of northern Tanzania because of its active hunting and gathering lifestyle, similar to early human survival methods. The Hadza tribe uses no electronics or climate control, and both male and female individuals sleep together in a mixed-age group in the outdoors. They live under constant exposure to meteorological pressures, other people, and animals, and they must adapt to these challenges on a day-to-day basis, similar to early humans.

Thirty-three healthy Hadza men and women were studied for a period of 20 days, during which their sleeping patterns were tracked with watch-like accessories that monitored their movements. They woke up often to smoke, relieve themselves, and watch over their children.

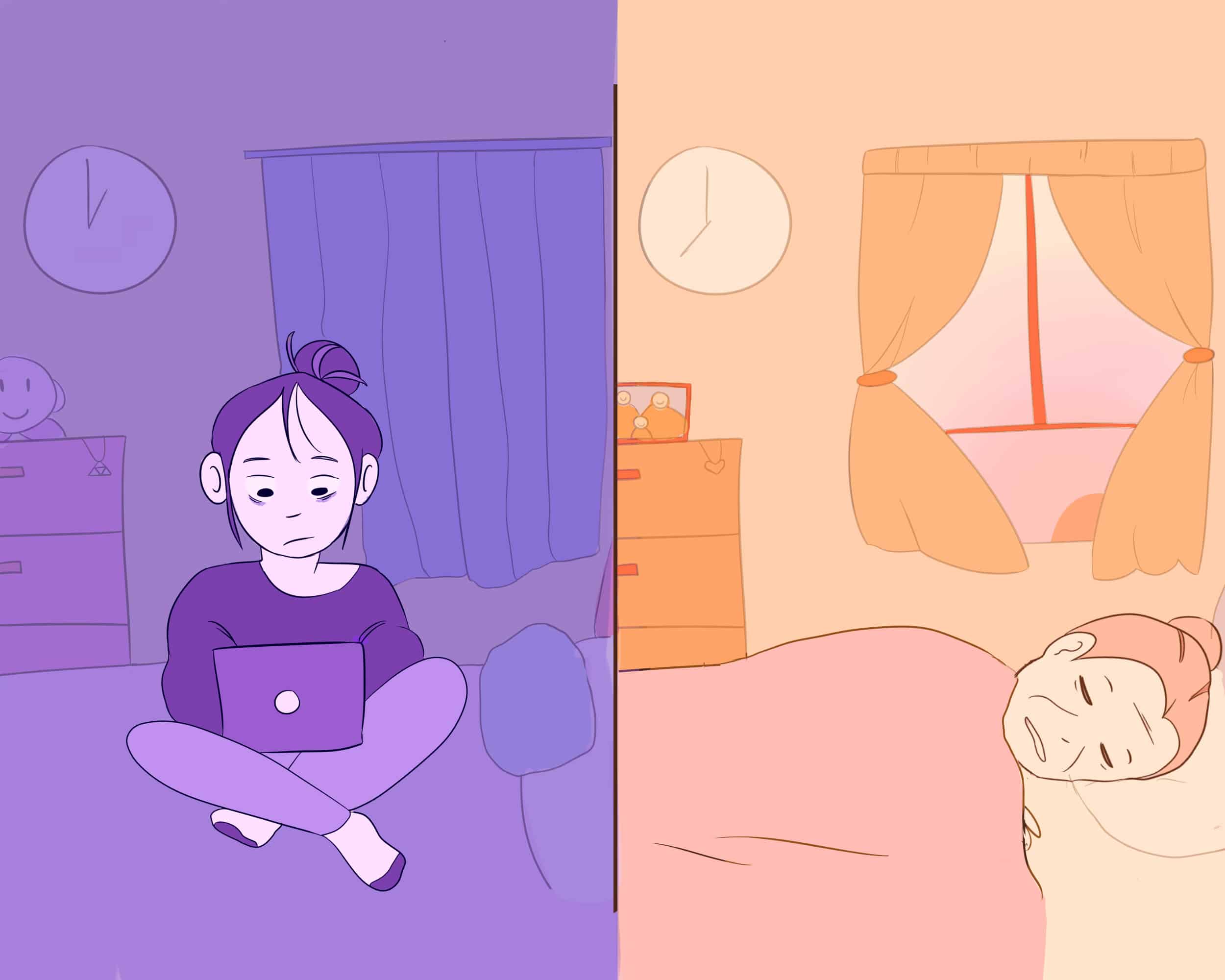

On average, the men and women slept for 6.5 hours each night. However, the older tribe members tended to sleep earlier in the night, whereas the younger members slept later. During the study, the participants were all simultaneously asleep for just 18 minutes.

“The discovery that Hadza hunter-gatherers have little to no synchronous sleep (at any given nighttime minute, 40% of the adults are awake) was very surprising and also strong support for the sentinel hypothesis in humans,” Samson wrote in an email to The Varsity.

Although the Hadza tribe leads a drastically different lifestyle from people living and sleeping in non-hunting and gathering environments, their sleeping habits mimic those of early human ancestors who defended against nocturnal predators and showcases our evolutionary history. These findings suggest that the unsteady sleeping patterns we face may not solely be attributed to cell phone or electronics usage, but may in fact correlate with our ancestry.

“In the West we have a tendency to label phenomenon that fall outside the statistical bell curve as non-normative,” Samson explained. “In fact, it may be that such variation was adaptive in our ancestral past, and we have an occurrence of ‘evolutionary mismatch’ — where our ancient hardware conflicts with our modern social and technological context.”

Samson hopes that these findings will normalize sleep flexibility and variability throughout an individual’s life, as well as reduce sleep anxiety and improve sleep quality. “My lab’s research will focus on measuring sleep-wake patterns in traditional people worldwide to generate a global sleep database,” Samson said. “Moreover, we will continue to measure sleep architecture all across the primate order to understand how non-human and human sleep differ from each other and other mammals.”

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the Hadza men and women slept for nine hours each night. They slept for 6.5.