This year’s Grolsch People’s Choice Award winner stands out from previous winners of the coveted TIFF award, which include La La Land, 12 Years a Slave, The King’s Speech, and Slumdog Millionaire. Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri is possibly the most cynical and blisteringly hostile movie to win the award in years, and TIFF is all the better for it.

At the helm of this train of bitterness is Frances McDormand, who rampages through the film — and the small town inhabited by her character — in a fashion reminiscent of Michael Douglas’ adventures in Joel Schumacher’s Falling Down. Don’t be surprised when Oscar buzz starts surrounding McDormand, because her performance here might be her best since 1996’s Fargo. Here, McDormand’s archetype of Midwestern niceness is channeled into the embittered Mildred Hayes, whose daughter has been raped and murdered in her small Missouri town.

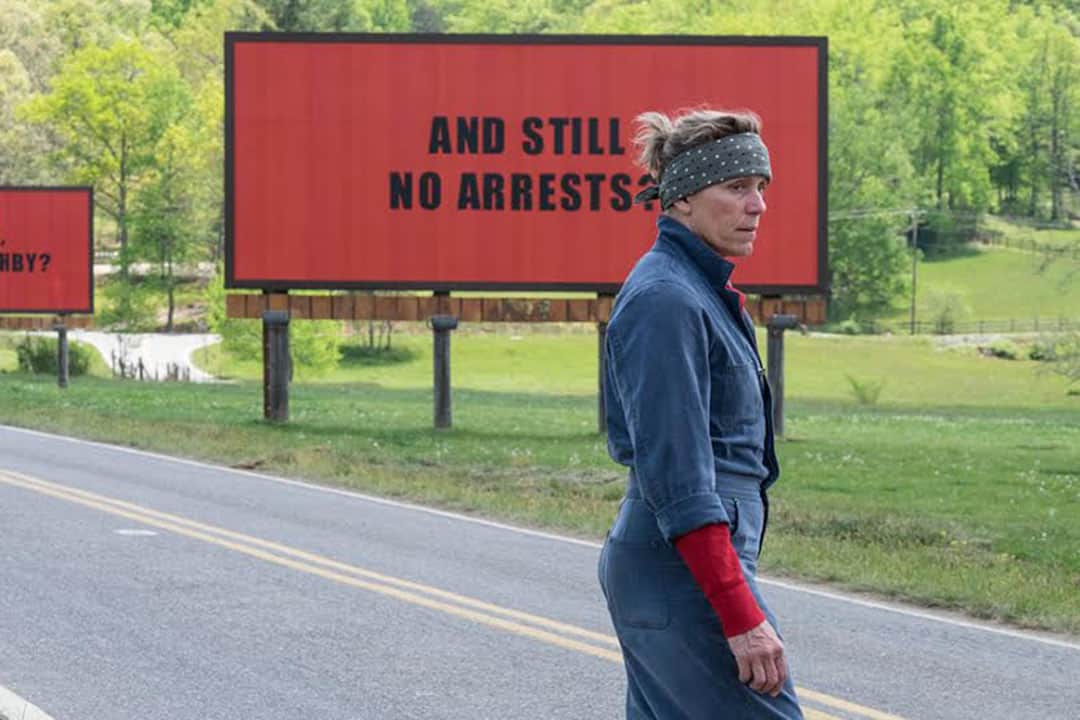

After months without news on the culprit from the police department, Mildred rents three billboards on a less-travelled road near the town and uses them to directly call out the police for their lack of results.

Director Martin McDonagh’s previous films, In Bruges and Seven Psychopaths, were great, at least in part because they were about horrible people caught in situations of their own horrible making. Yet here, in what may be his best film yet, McDonagh manages to pull off an altogether trickier task: making his characters not just funny or mean but thoroughly unpalatable through the questions they and the audience are forced to answer.

In doing so, McDonagh masterfully applies shades of grey to seemingly every level of this film. What happens to our anger when we realize that the police might have already done all they could? What happens to our sympathy for Mildred when she reveals herself to be a deeply problematic, impulsive, and violent person — much like the people from whom she wants to protect her children?

Credit must also go to the rest of the cast. Aside from an incredible turn from McDormand, Sam Rockwell stands out too, funnelling his genial and oddball image into the role of a friendly small-town cop who is racist, sexist, xenophobic, and frighteningly familiar.

A viewer will recognize a union of great writing and acting when it’s a struggle to distinguish a singular standout performance. Woody Harrelson is surprisingly sensitive, John Hawkes is heart-stoppingly menacing, and both Lucas Hedges and Peter Dinklage exhibit remarkable range.

Thanks to McDonagh’s writing and other factors including Carter Burwell’s beautiful and thoroughly southern score, this is a world that feels incredibly lived-in. McDonagh’s theatre sensibilities shine through as he crafts a small town that feels as intimate as any stage. The characters are noticeably emotive, emphasizing soft sighs, awkward glances, and choking back tears. Mildred’s anguish is visible in her every line and expression.

In some ways, this movie is not without contradiction. It will make you sympathize with a racist, and it might even make you hate its protagonist. More than anything, it’s full of lively and engaging characters that the viewer will come to realize are simply tired of what life has thrown at them — whether it be death, sadness, boredom, or anything in between.

A lesser movie might simply explain that life is unfair and that forgiveness is all we have. McDonagh knows this and wisely shows people as being full of dimension and far from the platonic ideal of tolerance as their anger, bitterness, and passion bubble to the surface.

By leaning into the mess and embracing the flaws of all its characters, the movie becomes a richly complex and memorable — not to mention hilarious — work of art.