U of T’s top earners are disproportionately male, The Varsity’s analysis of previous Sunshine Lists has revealed.

The annual Sunshine List, published by the Ontario government, reveals the salaries of all public employees who make over $100,000. There were 131,741 people on the 2017 list, over 3,800 of whom were University of Toronto employees.

The 2017 Sunshine List revealed a significant absence of women in top-paying positions, as well as a persistent pay disparity between the top earning male and female professors at U of T — even for professors with the same title, same years of employment, and the same starting salary.

The 2014–2015 gender equity report, the last-released study on gender equity at U of T, reported an increase in the representation of women in full-time tenure-track faculty positions from 30 per cent to 35 per cent. Women in the position of Professor made up only 27 per cent of all full-time Professors at U of T in the 2014–2015 academic employment year.

The top 100

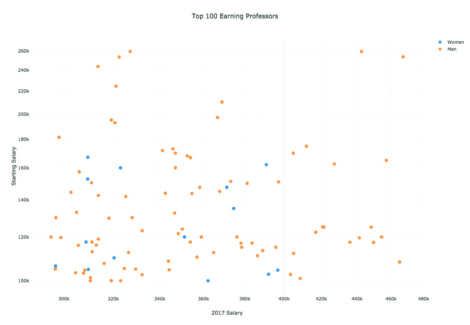

Professors with the top 100 highest salaries on the Sunshine List are from a wide variety of departments and all three U of T campuses, yet the majority are men, with only 14 women making the cut.

Median pay for the top 100 female professors on the 2017 Sunshine List was $337,105.74, whereas the median pay for men in the top 100 was $346,854.07. This translates to female professors in the top 100 making 97 cents for each dollar that a male professor makes.

While this is still a smaller gap than the Canadian average, it alludes to other larger disparities that can be seen throughout the Sunshine List, ranging from the median starting salary differences to the median 2017 salary for men and women.

While the average male professor has been on the Sunshine List for two more years than the average female professor, the overrepresentation of men on the list combined with the median salary gap of $9,748.33 points to a historical absence of women in higher-paying positions. In this regard, the top 100 list reveals no new information, as women are frequently underrepresented and unequally-paid in high-paying jobs.

A closer look at professors of Philosophy, Religion, English, Rotman Organizational Behaviour, Law, Mechanical and Industrial Engineering (MIE), Mathematics, Computer Science, and Physics reveals that, while the trend of pay disparity does not apply to every individual department, a pay gap occurs in all areas of U of T. These departments were chosen for analysis as they had the largest number of professors with the same job title on the 2017 Sunshine List.

Humanities and Social Sciences (Philosophy, Religion, English, Rotman, Law)

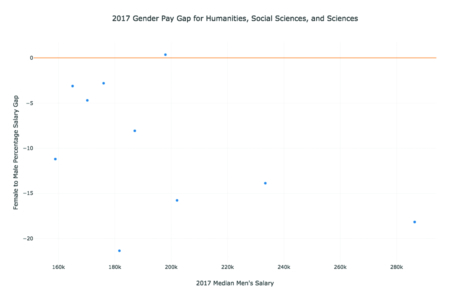

All of the Humanities and Social Sciences departments investigated had pay gaps across the board.

Female professors on the Sunshine List were, on average, hired only two years later than their male counterparts, yet consistently received significantly smaller pay raises across their careers and were always outnumbered in their departments. While these female professors saw an average increase from their starting salary of $48,012.73, male professors averaged a $78,103.22 increase.

While Religion, English, Rotman, and Law all had higher starting median salaries for women when compared to men, with gaps of $1,719.00, $1,401.50, $53,682.00, and $11,916.00 respectively, male professors still had a higher median salary on the 2017 Sunshine List.

Philosophy professors on the Sunshine List — all of whom had the same job title — held the smallest margin of median salary disparity, with a pay gap of $5,490.73 in favour of men in 2017.

The largest average pay gap in 2017 among these departments belonged to Rotman Professors of Organizational Behaviour and Human Resource Management, where women on the Sunshine List made, on average, 29 per cent less than men.

With the exception of Philosophy, these Humanities and Social Science departments all show the same characteristics: the average woman on the Sunshine List made less than their male counterpart in 2017 and departments with higher overall pay maintained increasingly wider divides in median and average pay.

Sciences (MIE, Mathematics, Computer Science, Physics)

While more egalitarian in pay when compared to the Humanities and Social Sciences, professors in MIE, Mathematics, Computer Science, and Physics — representing the fields of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) — had pay disparities favouring men in every department but one.

The largest pay gap in the Sciences existed among MIE professors on the Sunshine List, where only two women held the same title as their 28 male counterparts. While the median starting salary for women was $4,121.50 higher than for men, the current pay gap is commensurate with the employment gap — women on the list made 19 per cent less than men in 2017. This means that, though women may start out with higher salaries, they do not see as much progress throughout their careers as men do.

In contrast, Computer Science salaries were, on average, equal for men and women. The median pay gap was $711.67 in favour of women, an anomaly on the Sunshine List.

All Science departments analyzed had at least double the number of men than women on the Sunshine List. MIE had the largest disparity, with 26 more men than women, while Computer Science had the smallest gap, at 10 more men than women.

Physics and Mathematics both maintained a pay disparity between average starting salaries and average 2017 salaries. On the 2017 Sunshine List, women in Physics were paid 87 cents per dollar made by their male counterpart, and women in Mathematics made 94 cents per dollar.

In addition to the gender pay gap, the Science departments reflect a STEM-wide problem: the underrepresentation of women. Between 1987 and 2015, the percentage of women working in STEM fields across Canada increased from 20 per cent to 22 per cent of the workforce. By contrast, female science professors at U of T who appeared on the Sunshine List made up only 16.5 per cent of the investigated Science departments on the list.

Analyzing direct discrimination

When comparing professors within the same department, with the same starting salary within a $500 margin, and the same number of years of employment, direct gender pay disparity becomes much more apparent.

Among nine pairings with these conditions, only two had women making more than their male counterpart; the largest pay gap in favour of women was $4,296.36.

The other seven cases demonstrated greater gender-based pay inequities, with the largest pay gap in favour of men at $78,033.09. In this case, the male professor who started with the same salary and worked for the same number of years as his female counterpart still made 48 per cent more.

Broadly, the average starting salary across all nine cases was $106,885.11 for women and $106,792.56 for men. Though women on the 2017 Sunshine List had a small starting salary gap of $92.55, in the end the average man still made $14,993.06 more than the average woman.

Across the nine cases mentioned above, women made on average 9.6 per cent less than men in 2017, despite having been on the Sunshine List for the same number of years, with the same starting salary, and with the same listed job title. These cases, however, do not take into account external factors that would affect salary, such as teaching additional courses and conducting research. It’s unknown how these 18 male and female professors compare on those counts, as either the male or female professor could have more experience.

Responses and reactions

In a statement to The Varsity, U of T Vice-Provost Faculty and Academic Life Heather Boon said that, “The matter of gender pay equity is an important issue at U of T. We, like many other large and complex institutions, are in the process of looking carefully at gender pay equity as it relates to our faculty.”

Boon explained that gender is more balanced for Associate and Assistant Professors, citing the 2014–2015 Gender Equity Report that states that Associate Professors and Assistant Professors have 42 per cent and 43 per cent female representation, respectively. Any analysis comparing the pay of the most senior rank of Professor will be affected by the prevalence of men in those more senior positions.

Boon’s statement corroborates the findings of The Varsity’s analysis: the top 100 earning professors at U of T are overwhelmingly male, and make more money in almost every case.

Boon listed initiatives the university is undertaking “to foster and support a diverse faculty complement,” including increased funding to support diverse faculty hiring, unconscious bias training, mentorship and leadership programs for new and diverse faculty, and an updated equity survey that would collect detailed data on U of T’s workforce.

“The University of Toronto is one of North America’s leading research intensive universities,” concluded Boon. “We are committed to excellence in education and research. That requires us to attract and retain the best educators and professional staff with competitive salaries and compensation.”

However, Professor Sarah Kaplan, Director of the Institute for Gender and the Economy, Distinguished Professor of Gender and the Economy, and Professor of Strategic Management at Rotman, contends that little progress is being made to rectify the gender-based pay disparities and employment gaps at U of T, particularly for faculty on the Sunshine List.

Kaplan added that the Sunshine List “has many problems,” which makes analysis of it “a little bit apples to oranges.”

“For example, if a professor has a salary that is $100,000 but they teach two extra courses that year, they might get paid to just teach those courses in addition to that load, so their overall salary would look higher,” she said.

Despite the issues with the Sunshine List, it is the only publicly available data on U of T salaries. The university does not release any information on employee diversity, and the last report on gender equity was published based on data from four academic years ago. Although it isn’t perfect, the Sunshine List still demonstrates gender disparities at U of T’s highest levels.

“We’re not alone at U of T,” said Kaplan when discussing the pay gap in the wider Ontario and Canadian context. “But we’re a leading university in the country. We should not just be comforting ourselves by saying ‘we’re not alone.’ We should actually be at the cutting edge of trying [to] resolve this.”

Within Ontario, McMaster University, the University of Waterloo, and the University of Guelph have all enacted pay boosts to female faculty after task forces and studies revealed systemic gender-based inequities in salary. Kaplan believes that U of T should follow suit by collecting the appropriate data and equalizing pay. However, she has little faith that these changes will come swiftly. “In the university or government context, where change is going to be slow, it’s going to take some guts to do it and I don’t see anyone having the guts,” she said.

“[U of T] should recognize that there’s these gendered processes that produce these unequal outcomes,” said Kaplan. “They should be making up for those differences and be willing to take whatever political heat they would take for doing it.”

Index

average vs. median: The average pay calculates the arithmetic mean, which tends to be higher than the median, the middle of a given set. Whereas the average would account for wide ranges in pay, the median more accurately represents the ‘typical’ man or woman when considering pay. However, the average, in many cases, is able to fully reflect pay gaps by accounting for the overall higher pay among one group over another.

starting vs. current (2017): Ontario first began publishing the Sunshine List in 1996. The starting salary of professors who were researched represent their salary when they first appeared on the annually published Sunshine List.