Toronto has a rich history of radical politics. Over multiple generations, University of Toronto students have consistently taken the initiative as political participants and leaders.

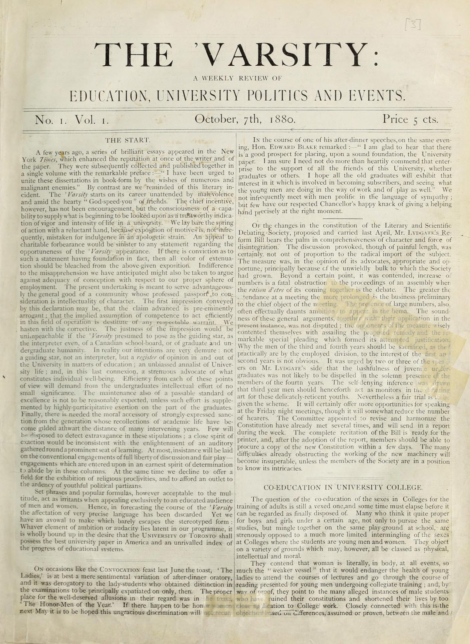

As early as the nineteenth century, U of T students have advocated for a more inclusive campus and improved broader community. The very first issue of The Varsity, from October 7, 1880 contains an article staunchly defending the then-contentious idea of allowing women not only entry into university, but the same access to programs of study, scholarships, and extracurricular activities as men. In that same year, students challenged conventional teaching methods, describing curricula as “too much reading… too little thought.”

These early years of recorded student activity are characterized by intellectual resistance, wherein students advocated for change and independent thinking. With that said, universities were still dominated by white, privileged men, who shaped the institution in their image — to the exclusion or marginalization of other groups. Nevertheless, these primary organizing ideas manifested into student organizations designed to facilitate the extracurricular activities and advocacy that students demanded. By the early twentieth century, U of T had a student government. Students would also play a key role in creating the National Federation of Canadian University Students in 1926, the first national student union in Canada.

In the city at large, radical politics in the early twentieth century took the form of grassroots social collectives, united under causes like feminism and anarchism. Toronto also sheltered political exiles from the United States, including the influential Emma Goldman.

Goldman was a Jewish-Russian immigrant who challenged all injustices she came across, including poor working conditions, a lack of social supports for the lower classes, and discrimination against women. This led her to join, and eventually lead, anarchist movements in Canada and the United States. Goldman lived in Toronto briefly, in a small walk-up apartment on Spadina Avenue, and died in a friend’s home on Vaughan Road in 1940.

Goldman gave speeches calling for many things taken for granted today, including birth control, tolerance of non-heterosexual orientations, an eight-hour workday, and banning corporal punishment in schools. Her actions attracted the negative attention of police, and she soon bore the nickname “The Most Dangerous Woman in the World.”

One of Goldman’s Canadian successes was halting the extradition of Attilio Bortolotti, a key figure in Toronto’s early anarchist movement. Bortolotti, an Italian immigrant, edited anarchist journals and advocated against Benito Mussolini’s policies from abroad. He was slotted to be extradited to Italy, and many speculated that once he’d arrived, he’d be killed by the fascist government for his dissidence. Goldman engaged in campaigns to raise awareness and garner public support about Bortolotti’s plight, successfully pressuring the Canadian government to cancel his extradition.

Despite the cataclysmic events of World War II and the resulting onset of the Cold War, radical politics in Toronto and on campus persisted. Tommy Douglas, described in a 1954 issue of The Varsity as “the only Socialist premier in Canada,” came to speak to U of T students in the fall of that year.

Throughout the early 1960s, The Varsity made it a priority to hear from those in society who had largely been silent in mainstream media, including communists, sex workers, and those suffering from drug addiction.

In 1960, the U of T Communist Club was founded. Their first meeting was crashed by a crowd of anti-communist students shouting “Rule Britannia,” attempting to drown out the communists. Supposedly, they gained a majority in the room and began to force the club to adopt anti-communist stances, such as the endorsement of Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s speech at the United Nations, which condemned the imposition of political and economic orders on new countries. The Varsity interviewed one of these communist students to get their perspective.

U of T students also flirted with communism abroad. A mysterious letter sent to The Varsity in 1960 under a pseudonym told an account of five U of T students who joined Fidel Castro’s resistance forces in Cuba to fight against the oppressive Bautista regime. According to the account, the students spent two months wandering through Cuban jungles until they found the rebels’ camp and met Castro himself, who welcomed them into his ranks. The students participated in military activities and were active members of the resistance movement. While The Varsity’s editors at the time questioned the truthfulness of the account, it was compelling enough for them to publish it with a disclaimer, and it has since become campus legend.

And then came 1968, a pivotal year for student movements, which saw unprecedented mass protests around the world in countries including Brazil, Mexico, Czechoslovakia, France, and the United States. The University of Toronto was swept up in this current, which saw a spike in activism on campus and in the city. Students impacted by a housing crisis in Toronto built a tent city outside of Hart House to call for change. This newly-formed community began to host their own events, entertainment, and advocacy initiatives to raise awareness about their need for accessible to housing. In fact, they became so organized that they arranged for ads in The Varsity to inform students about their upcoming activities.

While most U of T students were not directly affected by the Vietnam War and the military draft lottery that led to massive student protests south of the border, they still recognized the war’s controversial nature and empathized with their American counterparts. Fall 1968 saw a large protest consisting of students and local activists in front of the American consulate in Toronto, which resulted in a number of arrests and instances of police violence, including the beating of protesters and riding horses into crowds. A number of students wrote to The Varsity, denouncing the Toronto police as pigs, while a later issue was filled with letters from students defending the police as trying their best to maintain order.

During this time, student demographics were beginning to change significantly. The first scholarship students from Africa arrived at U of T in 1960, which in the same academic year prompted a series of articles calling out racist behaviours on campus. By 1970, a Black Students Union had formed, and the Students’ Administrative Council — now known as the University of Toronto Students’ Union — decided to allocate $5,000 annually to this organization to support marginalized students. In 1969, the University of Toronto Homophile Association (UTHA) was established to advocate for equal rights and freedoms for students of non-heterosexual orientations. This marked the first time that such a group had been organized in Ontario or at any Canadian university. The advocacy of UTHA activists helped bring about changes in paradigms of sexuality and gender in Canada and across the world. Today, the UTHA is now known as Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals and Trans People of the University of Toronto (LGBTOUT) and has a permanent space on campus for organizing a variety of events and programming for LGBTQ students.

While many Canadian protests in the 1960s had been in response to events in other countries, everything changed with the rise of the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ). Québec separatism exploded in the early 1970s with the election of separatist governments, mailbox bombings, and the kidnapping of politicians. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act and deployed the military in Québec to restore order. However, what is not well known is that martial law was enforced in other parts of Canada as well. Two University of Toronto students were arrested for allegedly supporting the FLQ, and their rights of habeas corpus were suspended under Trudeau’s invocation of the War Measures Act. Despite this, many U of T students were committed to bringing about a peaceful resolution to the conflict. Several meetings about the crisis in Québec were held on campus in 1970, with the ultimate conclusion being that U of T students should take action.

After two Indigenous women from Kenora were unjustly jailed in 1970, a protest was organized at Queen’s Park by Indigenous activists from across the province, highlighting the racist behaviour of the judge who presided over the case and Indigenous peoples’ limited access to legal counsel. In 1992, an organization now known as the Indigenous Students Association was formed, dedicated to providing community for Indigenous students on campus and advocating for their needs.

Environmentalism also began to catch on in the 1970s, with articles in The Varsity outlining how corporations were lobbying against environmental protections to make more profits. Other students began to theorize how these sentiments could develop into a lasting political movement to foster policy change.

The 1980s saw the rise of neoliberalism and a more conformist ideology spread through academia, which emphasized focusing primarily on academics and spending less time on activism. U of T seems to have felt some of this as well, with activism focusing more on smaller local issues like high rent prices. It was not until the 1990s that University of Toronto students would rise up again in large numbers, this time in response to the proposed tuition increases of the Progressive Conservative government in Ontario, led by Premier Mike Harris. Roundtables were held on campus that hosted prominent speakers like former NDP Ontario Premier Bob Rae, who encouraged students to build coalitions with other community groups.

Over 7,000 people attended a protest at Queen’s Park in 1995 to challenge the Harris government’s budget cuts to education. As in 1968, police tried to disperse the demonstrators. A column of officers in full riot gear, 14 wide and five deep, advanced toward the protestors, beating anyone in their path with batons. Then-U of T student Allison Starkey, who attended the protest, described an incident in which a police officer cracked open the skull of a mother of four with his baton. Student leaders were influential in the protest, with Arts and Sciences Students’ Union and Graduate Students’ Union representatives and members asserting their presence among a number of students from Toronto secondary schools. The Students’ Administrative Council was criticized by students for not formally attending the protest.

The twenty-first century would in many ways see a continuation of advocacy for the social issues brought to the forefront in the twentieth century, and in some cases these issues would blend together. The 2008 financial crisis prompted the formation of a number of social movements designed to highlight economic inequalities by physically occupying areas of cities where financial power was concentrated. Occupy Toronto was one of these groups, formed in 2011, which organized a 40-day protest with activists setting up camp in St. James Park. From their encampment, the activists would go to Toronto’s financial district to engage in a series of demonstrations. The camp was largely sustained through the generosity of Toronto residents.

Other, more organic protests formed in response to the G20 summit held in Toronto in 2010, with activists challenging elite politicians and discriminatory economic policies, as well as the cost to Canadians to host the summit. Police established a temporary detention centre and arrested over 1,100 people, most of whom were later released. A report by the city’s Office of the Independent Police Review Director released two years later outlined that police tactics during the protests had breached Canadians’ constitutional rights.

It may be argued that in recent times, student engagement in advocacy activities and political participation in Canada, outside Québec, is insufficient and has little genuine influence on policy. However, students today benefit from powerful democratic student unions that, in addition to advocacy, provide services to help improve the quality of education in spite of unfavourable economic and policy trends.

Identifying issues and working together as students necessitates communicating effectively between large numbers of students. An independent student press is crucial for highlighting important issues for students today and tomorrow. At U of T, we’re lucky to have multiple student newspapers. Similarly, extracurricular groups on campus need to work together to engage their members toward common goals. A good way to facilitate campus coalitions is to host joint events and activities where different memberships can develop friendships and exchange ideas. Cooperation between undergraduate and graduate student organizations, and even secondary and postsecondary students, is particularly valuable.

Furthermore, students should always ensure that their own organizations, especially student unions, have fair decision-making processes. Any authoritarian practice, including excessive power in the hands of unelected officials, financial mismanagement, discrimination, lack of transparency, or interference with democratic processes, should be challenged. That way, we’ll be ready for future crises.

As history shows, a strong framework for student advocacy exists, and can continuously be improved. The challenge lies in identifying tangible policy goals and the accompanying political tactics that would be the most successful in achieving them.