Last week, the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) finalized plans to build The Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life. As its name suggests, the Dawn of Life will feature fossils from the start of life about four billion years ago until the appearance of dinosaurs over 200 million years ago.

Professor in the Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology and Department of Earth Sciences Jean-Bernard Caron and his research team travelled to the Burgess Shale and collected some of the fossils that will become a focus of Dawn of Life.

“Without the close relationship we have with U of T, this would not be possible,” said Caron, who is also the Richard M. Ivey Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology at the ROM. “Without students, my collection would be a pile of rocks.”’

Showcasing Canada’s ancient past

The Cambrian Explosion occured 542 million years ago. This period marked the rapid appearance of diversified animals and mineralized fossils.

The Burgess Shale in British Columbia contains a myriad of fossils from the Cambrian period. In particular, the Burgess Shale is known for its intricate preservation of soft-bodied animals. Many of the fossils from this UNESCO World Heritage site provide a wealth of information that cannot be found anywhere else.

Caron initiated the Burgess Shale projects after joining the ROM in 2006, providing insight into Canada’s ancient past.

In addition to the Burgess Shale, fossils from Mistaken Point in Newfoundland, Parc national de Miguasha and Anticosti island in Québec, and Joggins Fossil Cliffs in Nova Scotia will also be on display.

Featured fossils

The fossils in this exhibit are not only relics of the past, but are also representative of Canada’s rich archaeological history.

In 1886, Canadian geologist Richard G. McConnell collected fossils from the Mount Stephen Trilobite Beds in the Canadian Rockies. McConnell ended up with a collection of trilobites, one of the earliest arthropods. But he also recovered fossils that didn’t belong to trilobites. These fossils had unusual appendages and created confusion among researchers who followed in McConnell’s tracks.

In 1892, Joseph Whiteaves described the specimen as a shrimp. In 1911, Charles Walcott found a complete version of the specimen and described it as a sea cucumber. Other researchers throughout the twentieth century described the specimen as a sponge or jellyfish.

It wasn’t until 1985 that researchers Harry Whittington and Derek Briggs described two of the species in full, one of which is Anomalocaris canadensis, a basal arthropod related to spiders and shrimp.

Anomalocaridids were large predators that dominated the Cambrian seas roughly 535 million years ago.

In the 1990s, researchers from the ROM collected several, complete Anomalocaridids specimens. And in 1996, researcher Desmond Collins described Anomalocaris canadensis in detail.

This specimen is one of many treasures that will be on display in Dawn of Life.

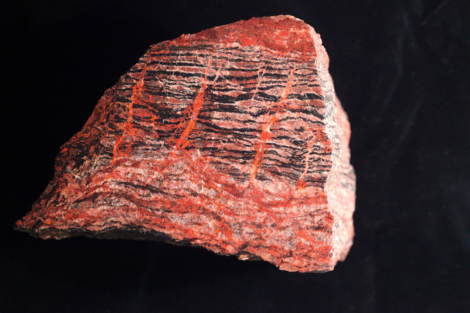

Visitors will also be able to view banded iron formation — from the Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt in northern Québec — which contains the earliest evidence of life on earth.

At the preview last week, visitors had the chance to see Acutiramus macrophthalmus in person. The fossil is the world’s largest specimen of its kind. It’s not evident from its large size, but the 420-million-year-old specimen is a distant relative to horseshoe crabs.

A 370-million-year-old Eusthenopteron fish and a Xenasaphus devexus trilobite are examples of some of the other fossils that will be featured.

Construction of the Dawn of Life is slated to begin in 2019 and the ROM hopes to open the exhibit in 2021. Meanwhile, a preview of the gallery is located on the second-floor rotunda.