Plastic waste is pervasive in all ecosystems, including Canadian freshwaters. It is estimated that every year, approximately 22 million pounds of plastic debris make their way into the Great Lakes. These plastics degrade over time and turn into microplastics, which are particles of plastic less than five millimetres in length.

The ecological consequences of plastic pollution are documented in a recent study led by researcher Keenan Munno of U of T’s Rochman Lab, in which she and her team discovered high concentrations of microplastics in fish from Lake Ontario, the Humber River, and Lake Superior. “In this paper, we found that 100 per cent of fish that we looked at had plastics in their [gastrointestinal] tract,” Munno said in an interview with The Varsity.

She went on to explain that most studies show that between 20 to 40 per cent of fish contain plastic particles, but 100 per cent of the fish that her team studied were contaminated with plastics. The level of plastic contamination in each fish was also extremely high, with rates of up to 900 plastic particles per fish.

The source of microplastics

Unlike in many similar studies, Munno and her team found a diverse array of microplastic particle types in the fish they studied. “What that tells us is there could be a number of potential sources, if we were trying to trace it back to see where the microplastics come from,” said Munno.

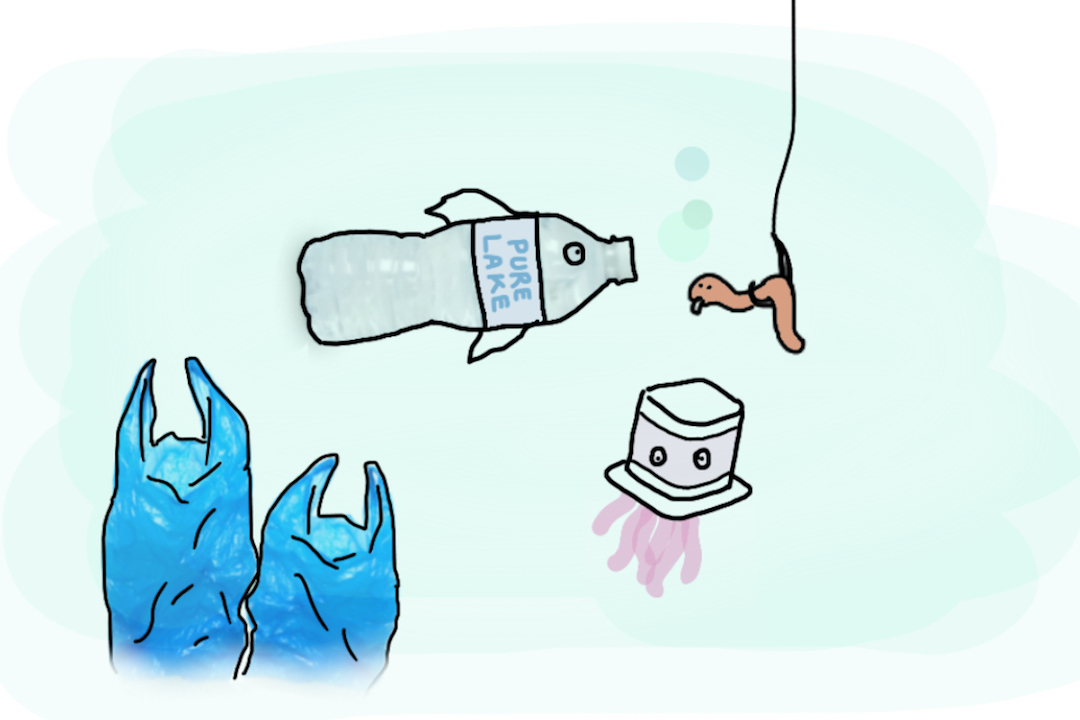

Microplastics often enter our ecosystems through our wastewater, which is why Munno and her team fished near wastewater outflows. Not surprisingly, the most abundant type of particles contaminating the fish were fibers, which are often shed from synthetic clothing and are washed down our drains. Other microplastics that Munno observed indicated that fish were consuming irregularly shaped remnants of larger materials, such as plastic water bottles.

Long-term ecological effects

According to Munno, quantifying the amount of plastics consumed by fish is the first step toward assessing what the long-term effects of their plastic consumption would be. “These fish are eating a lot of plastic — so, a lot more particles than we usually see them eat — and if eating that plastic makes them feel full, and they eat less nutritious food, that could have long-term effects,” Munno said.

While the long-term ecological effects of microplastic contamination in aquatic life are not fully understood, multiple studies have shown dire conclusions. For instance, a 2013 study led by Chelsea Rochman, Munno’s supervisor, demonstrated that dietary exposure to plastic causes liver toxicity in a type of Japanese fish.

Do microplastics pose health concerns for humans?

Commercial fishing in the Great Lakes results in approximately 50 million pounds of fish harvest each year. These fisheries contribute to the diet of nearly half of the Canadians that report regularly eating seafood at home, according to a 2011 survey.

While seafood is lauded for its health benefits, microplastic contamination in fish naturally raises concerns, and for good reason: it is estimated that people may consume up to 52,000 plastic particles per year, with seafood being a major contributing source.

While further research is necessary to understand exactly how microplastics impact humans, multiple studies have indicated that exposure may cause neurotoxicity, increased cancer risk, and other repercussions. In order to study the effects of microplastics on humans, Munno and an undergraduate student she is working with plan to go back to her study sites to retrieve fish that people commonly catch and eat. They will analyze microplastic contamination in their gastrointestinal tracts as well as their filets — the part of them that is usually consumed by humans.

What can be done?

On an individual level, people can avoid single-use plastics, such as disposable cutlery and water bottles, which eventually become microplastics. “There are also filters that people can buy and put on their washing machines that help trap more of the microfibers [shed by synthetic clothing],” Munno said.

Students can also take action by joining the U of T Trash Team, which is focused on reducing plastic pollution through cleanups and public outreach. The Trash Team also utilizes Seabins, which are floating garbage bins designed to collect 3.9 kilograms of aquatic debris per day, including microplastics.

Munno said that she and her colleagues have been pushing for regulations in the plastic industry that mandate putting traps on drains to prevent the debris produced by plastic manufacturers from entering freshwaters.

In good news, some recent policies about curbing microplastic production may already be making a difference. “One example is [that] microbeads in cosmetic products are banned in Canada — and a lot of this is just anecdotal, but we don’t find them very much in our samples anymore,” Munno said.