Classicism is an aesthetic attitude that centres around emulating the art, literature, and culture of ancient Greece and Rome. The style of classicism is based on Greek and Roman models and, especially in visual art, often centres around objectivity, simplicity, and emotional restraint.

However, beyond simply being an aesthetic attitude, classicism is also a pervasive social force. Greek and Roman models continue to influence every aspect of modern Western civilization, including our architecture, system of government, laws, and art. The omnipresent impact of classicism on our society not only influences its structure, but also the ways in which we are taught to perceive the world around us.

Yet, in doing so, classicism fails to account for Indigenous ways of knowing. This ignorance toward Indigenous perspectives is present throughout North America, as white settler colonialism brought with it the notion of the cultural superiority of ancient Greece and Rome.

In a desire to emphasize Indigenous perspectives in the classics, Katherine Blouin — an associate professor at the UTSC Department of Historical and Cultural Studies — designed a new course titled CLAC02 — Indigeneity and the Classics. This course is offered by the Department of Classics of the University of Toronto and became available at UTSC this fall.

The course examines how Indigeneity is represented in the ancient Mediterranean world, as well as the connections between current settler colonialism, historiography, and acknowledgement of the “classical past.” This course’s framework and flow are designed to bring ancient and current Indigenous ways of knowing together. In doing so, the course challenges the conventional teaching methods established by white settler colonialists and allows students to learn from an Indigenous perspective.

As such, in the end, students will leave the course with a greater understanding of the vibrancy and richness of ancient and present Indigenous cultural forms and knowledge, and better insight into the place of both the classics and ourselves on Turtle Island.

Traditionally, the study of the classics is an elitist and antiquated discipline that stands on a pedestal of whiteness and, in doing so, stifles Indigenous voices. However, by teaching both the classics and their connections to Indigeneity at the same time, Blouin brings the study of the classics down from its pedestal of ‘cultural superiority.’

According to Blouin, a key feature of the course is instilling a sense of “constructive discomfort” in students that gives them the ability to “carry themselves into the world… in a way that is more mindful of their positions on Turtle Island and especially on whose land they’re on and how they can limit the harm that they’re doing.” To accomplish this, Blouin incorporates several evaluations into her curriculum that challenge students to acknowledge the Indigenous presence in the world around them.

All settler colonies are located on the traditional ancestral colonies of Indigenous peoples. Even in Canada, every location is a part of Indigenous peoples’ long-established ancestral territory on Turtle Island. As part of an assessment titled “Where are you?” students are tasked with considering who formerly inhabited the land they are living on, including the oldest ancient Indigenous and settler groups. In doing so, students recognize that to live in a settler colony is to be territorialized by Indigenous peoples — that is, to live on land that belongs to Indigenous peoples.

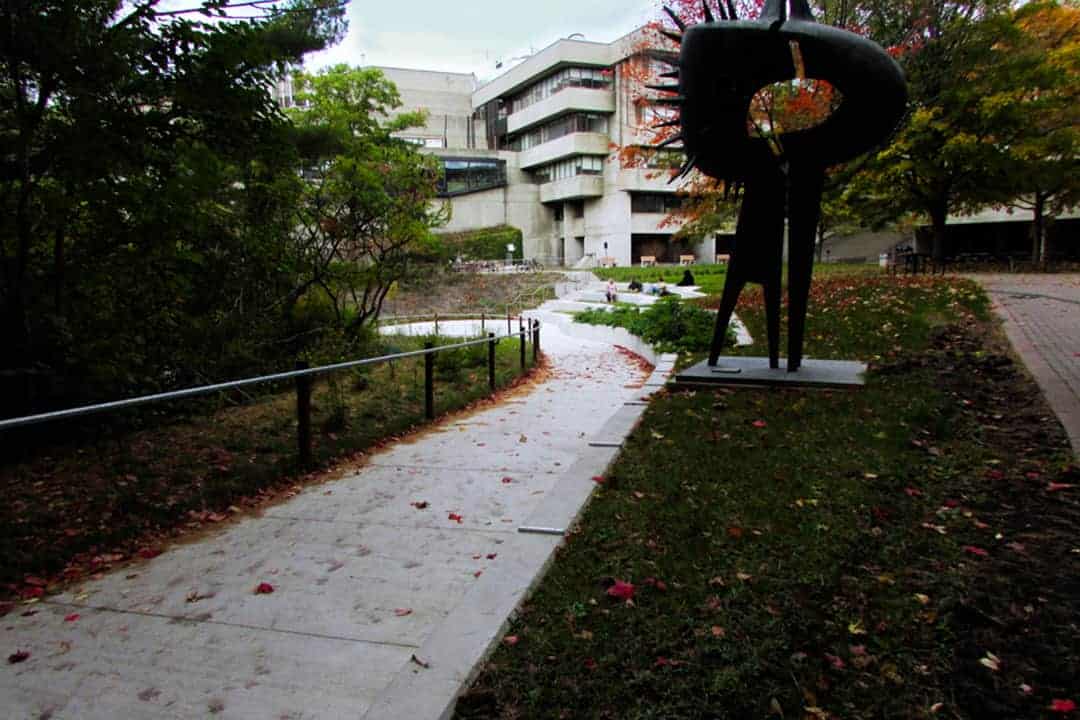

As part of the course, students are also taught to critically analyze the role of classicism and Indigeneity in architecture and the arts by closely examining monuments and museum exhibits. As a result, students learn how history, art, and architecture have traditionally been depicted from a classicist’s perspective.

The enduring and ever-present influence of classicism perpetuates archaic and Eurocentric ideals that ignore Indigenous voices. However, by focusing on the entanglements between the classics and Indigeneity, Blouin is changing the narrative to one that examines classicism with an Indigenous perspective in mind.

It’s worth noting that the classics is not the only discipline that has traditionally been westernized and, as such, stripped of Indigenous ways of knowing. Other subjects, such as the sciences and history, have commonly been taught from a Eurocentric perspective. The reality is that many disciplines have been developed from the perspective of white settler colonialists. As a result, Indigenous ways of knowing are often neglected from study.

To further develop Indigenous perspectives in education, more Indigenous-centric courses — courses like CLAC02 — should be encouraged throughout U of T. In addition, other departments should examine approaches through which they can implement Indigenous perspectives into their programs. In doing so, we can begin to acknowledge the presence of Indigeneity in education.

Education lies at the core of societal change. In that light, decolonizing society first begins with decolonizing the classroom.

Shernise Mohammed-Ali is a third-year neuroscience, psychology, and English student at Victoria College. She is the associate comment editor at The Varsity.