The University of Toronto’s recent announcement that it will completely divest from fossil fuels by 2030 was met with celebration from campus climate advocacy groups. But does this plan include the university’s federated colleges?

While we should rejoice over the university’s sudden change in tune toward divestment, we must remember that its new goals will not apply to all U of T colleges.

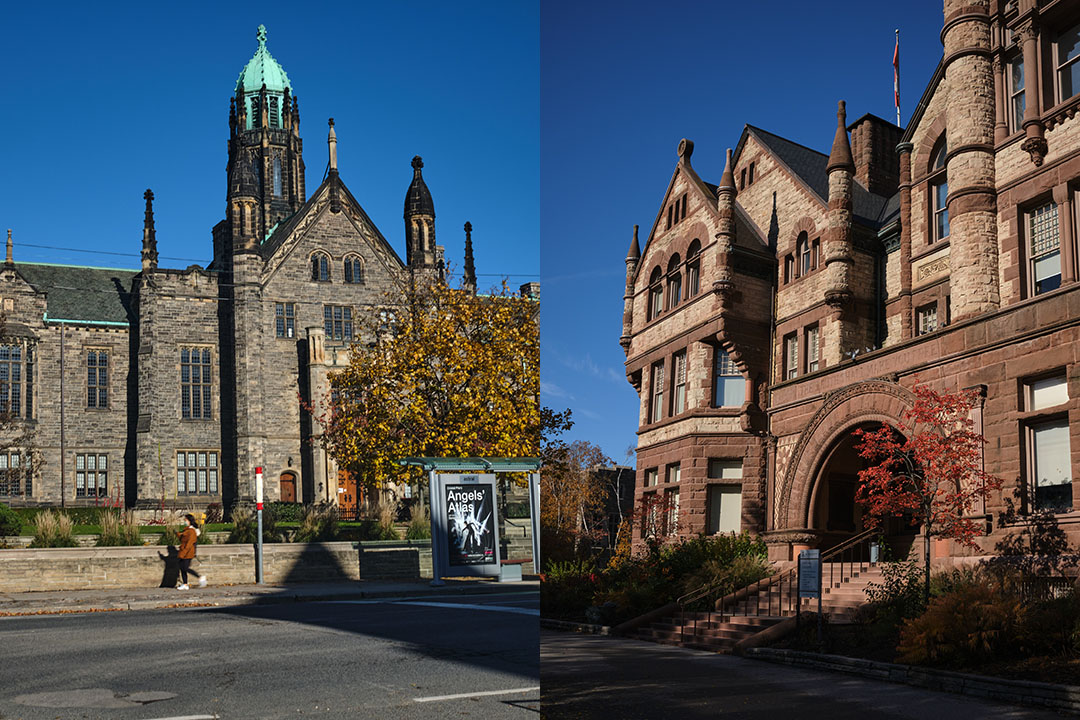

If you have ever wondered why the federated colleges Victoria, Trinity, and St. Michael’s are formally distinguished as their own ‘universities’ within U of T, there is a long historical explanation. The short answer is that the title indicates a difference in autonomy. While Woodsworth, Innis, University, and New College are largely under the jurisdiction of U of T’s central governing body, the federated colleges have special control over their programming, faculty, student intake, and — most importantly — finances. Therefore, U of T’s divestment pledge does not extend to the federated colleges.

Victoria, Trinity, and St. Michael’s possess large endowments that total to hundreds of millions of dollars. Although the three colleges have published their financial statements online, the pathways of their investments have been artfully obscured by a dictionary’s worth of financial jargon. The documents yield few substantial clues to the college’s holdings — and where clues are available, they turn up dead ends. The federated colleges are, no doubt, hiding their investments from their students.

It is a rather public fact that Victoria is the wealthiest of all the colleges. If you spend enough time on Victoria’s campus, as we did while we were students there, you will start to notice that every tour guide who passes by the college describes it to their herd of prospective students as “the college with the most money.” Certainly, they are correct: looking at their financial statements from 2019, Trinity and St. Michael’s have rather impressive endowments, at $69 million and $88 million respectively. However, these sums are made small in comparison to Victoria’s endowment, which clocks in at a mindblowing $507 million.

Victoria has been called out before on issues of sustainability, but its lips are still sealed about divestment. Students in Leap UofT and the Victoria College Sustainability Commission have demanded that the college divest from fossil fuels, but their efforts have been met with little more than fluff-piece statements. In response to a 2018 campaign by the Victoria College Sustainability Commission, Victoria University President and Vice-Chancellor William Robins deflected student concerns around Victoria’s environmental track record, emphasizing the college’s commitment to encouraging “waste diversion” on campus and bringing “greening initiatives” to its Physical Plant.

Taking care of the trash is all good and well, but it does not answer the question: where is Victoria’s money coming from, and where is it being held? Victoria’s financial statements reveal almost nothing about its investments, but we do know that as of 2019, the college invested in properties with ‘mineral rights’ in a small town in Saskatchewan that sits directly on an oil patch. But the Saskatchewan property is likely only a small piece of the puzzle.

With the college’s staggering endowment, it is entirely possible that Victoria has significant investments in stocks tied to oil and gas companies and the big banks that fund the fossil fuel industry. Only the college can confirm or deny this possibility. Victoria has a moral and fiduciary responsibility to disclose any financial relationships with oil and gas companies, and it is failing the U of T student community by not making their financial statements detailed and transparent.

The other federated colleges offer varying accounts of their holdings. Although St. Michael’s offers virtually nothing about its holdings in its 2019 financial statement, we do know that the college belongs to the University Network for Investor Engagement, an initiative that urges corporations to reduce their carbon emissions. This is not enough. The fewer details in colleges’ financial statements, the more pressing it is that we get honest answers from them.

Trinity’s statement reveals that a significant portion of its money is invested through Fiera, an independent asset management firm. Of the $106 million that Trinity invested through Fiera in 2019, $24 million was allocated to the Ethical Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Fund in Fiera’s Canadian Equity portfolio. Despite its ‘ethical’ and ‘environmental’ branding, in following Fiera’s ESG page to its Canadian Equity strategy, it appears that two of its top 10 holdings are in oil and gas companies, and another three are in big banks that fund the fossil fuel industry. To make things worse, one of the companies — TC Energy — is the owner of the much-criticized Coastal GasLink pipeline that continues to violate First Nations’ rights and contributes to the worsening climate emergency.

Although some details can be found in the federated colleges’ financial statements, the picture is by no means any clearer. Most of the information seems to be locked behind closed doors and shared through private meetings. Only Victoria, Trinity, and St. Michael’s can confirm how or where their money is invested.

We call on the federated colleges to release the records of their holdings in fossil fuel industries and the banks that back them, as well as a plan for matching U of T’s divestment timeline. Without this plan, students cannot know that these colleges practise the progressive values they preach, or that they support students’ rights to a future on a liveable planet.

Jared Connoy graduated from U of T in 2020 with a Bachelor of Science in economics and environmental science. He served as Victoria College Sustainability Commissioner from 2017–2019.

Grace King graduated from U of T in 2021 with a Master of Arts in English. She is a former member of Climate Justice Toronto.