I can’t remember the first time I stayed up all night to get work done, but I will never forget the one and only time I was awake for 72 hours. To be fair, I don’t remember the events of those three days clearly — they’re more of a hazy memory of bathroom mirror pep talks and trying not to fall asleep in coffee lines.

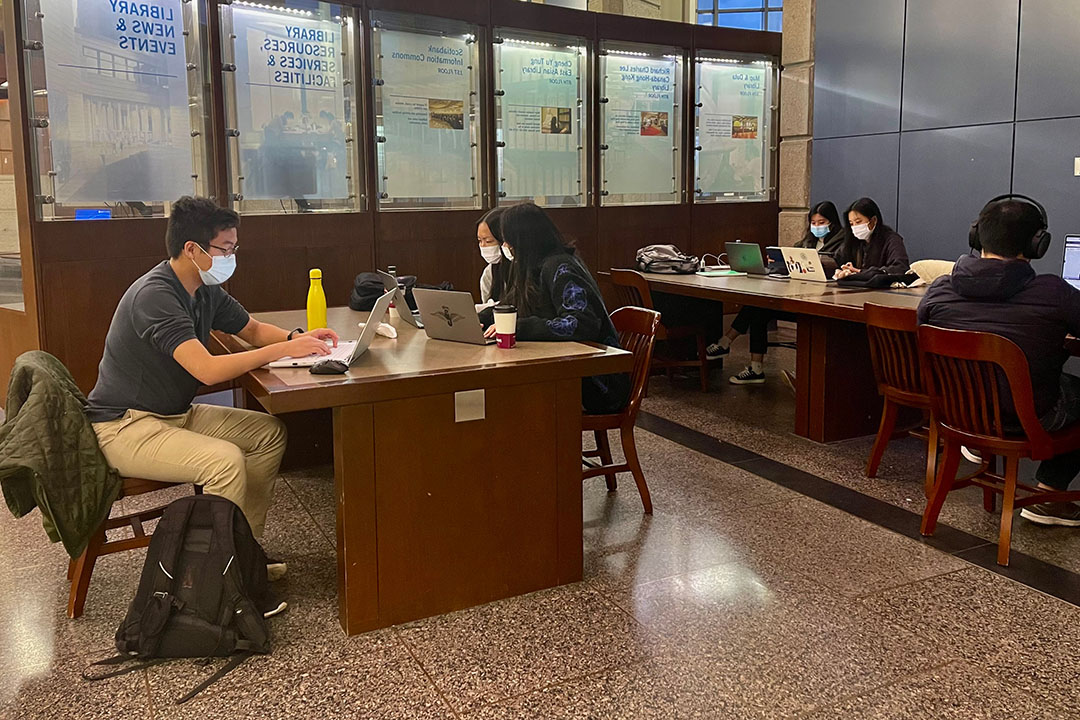

Admittedly, 72 hours is on the extreme side of the all-nighter spectrum, but the unsettling part is that during those sleepless nights, I was far from alone — the entire time, I was surrounded by fellow students also taking advantage of the extended hours being offered at Robarts Library at the time.

As a fourth-year student who is now hopefully wiser than I once was, I realize that this kind of torture is not worth the risks. It actually has a name: ‘toxic productivity’ refers to the desire, or even compulsion, to be productive at all costs, even at the expense of one’s health.

I should clarify that the compulsive nature of toxic productivity refers to an obsession with productivity, rather than productivity out of necessity. For example, working long hours due to financial need is different from being productive solely for productivity’s sake. In this article, I want to highlight problems with the latter, not suggest that we’re always able to take time off.

Although it’s difficult to determine the origin of the term ‘toxic productivity,’ it’s easier to pinpoint the beginning of its popularity. When I searched in U of T’s library database, all the papers I could find referencing it were written either in 2020 or 2021.

This makes sense, given that the pandemic has, for many, merged the once distinct realms of workplace and home, causing work to encroach on what used to be a space for relaxation and reflection. But while it’s reasonable to assume that the pandemic has worsened its effects, toxic productivity existed before the pandemic and could continue to have an even more powerful hold on us beyond the reach of lockdown.

Now back on campus after a remote third year, I have this urge to work harder; after experiencing setbacks due to the pandemic, I feel extraordinary pressure to get back on track. I don’t believe I’m the only student with this compulsion to be extra productive as a kind of compensation for a year I spent in isolation.

It may seem like common sense to avoid toxic productivity. I mean, I knew staying awake all night was unhealthy, but I did it anyway. The reality is that students ignore sensible arguments due to anxiety over their future, fear of failure, and the pressure to compete. The need to distinguish oneself from the masses at large schools like U of T only fuels students’ anxiety.

Toxic productivity is also aggravated by social media’s unique ability to make us feel inadequate: if you think you’re surrounded by smarter, more talented people, then it’s easy to believe that the only way to stand out is to work harder. In this world of constant comparisons, it’s no wonder that many students become anxious, depressed, or dependent on stimulants like Adderall in an attempt to maximize their efficiency.

Not only is toxic productivity dangerous, but it also might not actually be very productive. Research on the process of memory consolidation shows that people need time to transform short-term working memories into long-term ones — time that we often don’t allow ourselves. So unless our idea of productivity is nearsighted, we should leave room for calm reflection.

Also, the majority of scientific breakthroughs, cultural movements, and artistic brilliance result from inventive, imaginative, original thinking — something that’s hard to come by if all of a person’s time is spent maximizing productivity. We shouldn’t ignore the benefit of the time we spend being creative. Students are often told that the difference between a B and an A is originality; if great essays include original ideas, then students should allow themselves quiet contemplation to see beyond the course readings or to make personal connections.

Furthermore, toxic productivity implies that productivity is an end goal rather than the natural result of a well-thought-out plan. In the framework of toxic productivity, people do not really prioritize creating plans for personal growth. Personally, I spent so much time during university completing steps toward a goal that I’d outgrown. It took me until my third year to accept that I needed to take time out to think things through, and that led me to eventually switching majors and improving my mental health drastically.

It might seem like a losing battle, but I’m optimistic about combatting toxic productivity. Although mental health initiatives aren’t perfect, people have generally become more aware of mental health concerns, and the negative effects of the pandemic on mental health are well documented. I’ve personally found that professors are extra accomodating in light of the pandemic, so students should also allow themselves time to heal.

Although the long-term solution requires rewriting deep-rooted societal narratives that overprioritize productivity, students can combat toxic productivity every day by setting time aside to address feeling overwhelmed or directionless.

As a student who now realizes the dangers of toxic productivity, but who also understands the at times overpowering desire for success and fear of failure that many students feel, here’s my proposal: if time is our most valuable commodity, let’s use it wisely. Long hours spent trying to be productive are misspent if we aren’t also taking the time to reassess our goals, nourish our creativity, and attend to our health.

Anna Simeone is a fourth-year philosophy and Portuguese student at St. Michael’s College.