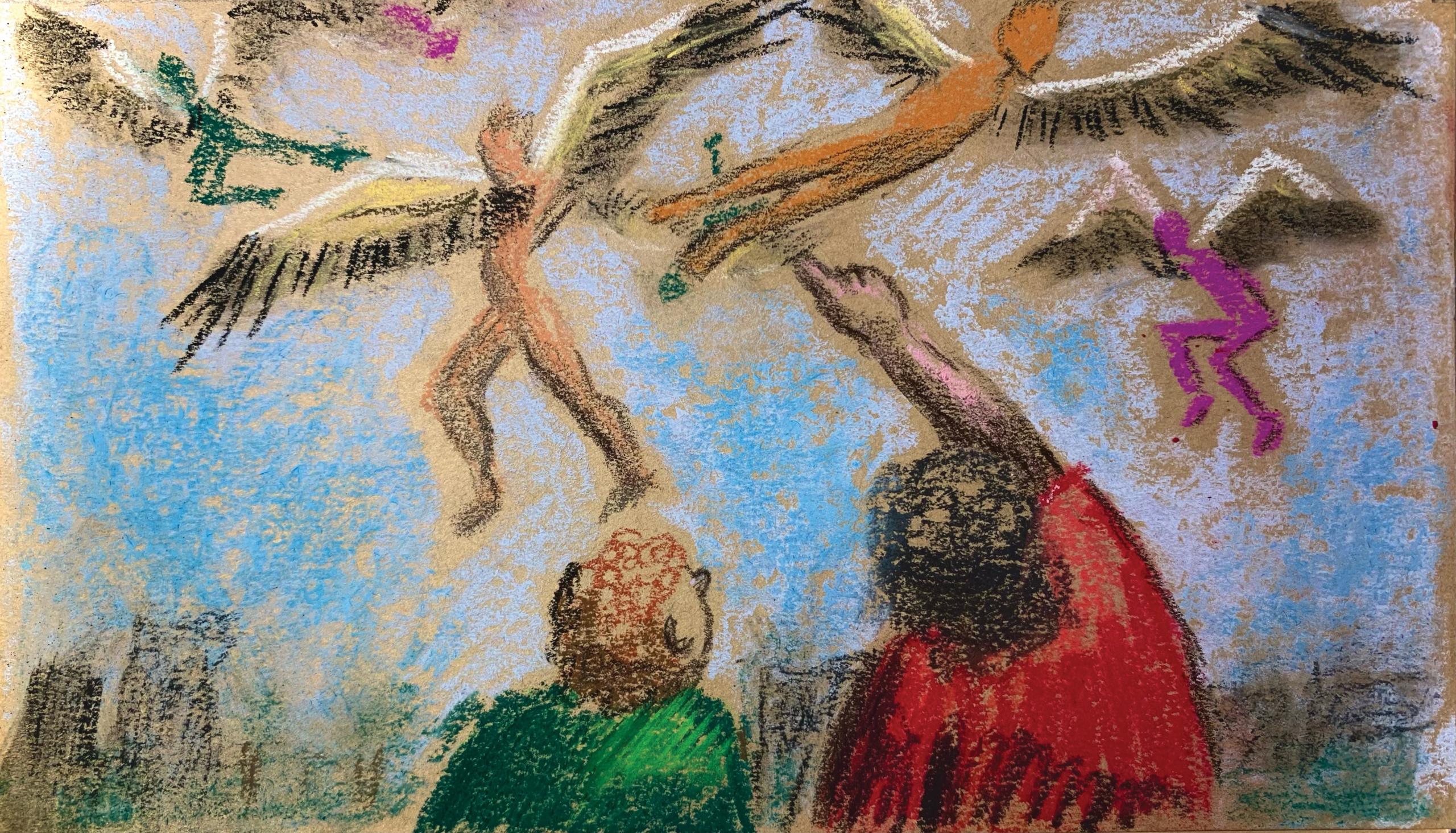

Imagine you’ve stepped off the top of an 80-storey skyscraper. You’re falling, falling fast. Your shirt flutters in the wind. Your hair whips around your face. You open your mouth to scream but the wind muffles your voice. You see the sky, then the building, and then the sky again as you tumble through the air, plummeting towards the ground at 200 kilometres an hour. Gut clenched, arms flailing, you shiver as the adrenaline takes over and your body starts tingling.

You’re going faster and faster, the ground is getting closer and closer, and just as you’re about to crash into the concrete pavement, you push your shoulder blades together, forcing your wings to flap open. The unfurled appendages catch the wind, tug you upwards, and now you’re gliding.

You’re swimming through the air, in control, flowing with the wind instead of just being thrown against it. You strain your back muscles and flap your wings, rising a little higher. You’re not falling anymore. You’re flying.

The allure of flight

Individual flight has long captured people’s imaginations. The Greeks tell the myth of Icarus who used wings made of wax and feathers to escape his confinement. Judeo-Christian texts describe angels that could fly up to the heavens. Leonardo da Vinci spent days designing flying machines that would mimic birds and let humans take to the skies.

Just looking at an eagle gliding through the air gives us land-dwellers a pang of jealousy. For us, the sky is forbidden, unconquered. Although we have our airplanes and our jets, flying in a big metal tube and peering through those tiny oval windows doesn’t quite fulfil that primal urge to feel the wind in our wings.

So why, even after thousands of years of innovation and research, are we still forced to sit in our cars and complain about the traffic instead of just flying above the road?

Why can’t I flap my wings open and go over to my nearest McDonald’s fly-through? Why are we chained to the Earth when we so long to fly?

It might have something to do with the fact that we humans just aren’t designed to fly. Surprise, surprise! Unlike those of birds or bats, our bodies are heavy, our muscles are weak, and probably most significant of all, we don’t have wings.

Yet.

Wings of flesh and bone

In an interview with The Varsity, Douglas Blackiston, a developmental biologist at Tufts University, shared his research on tissue plasticity and the development of wings.

His research involves understanding and changing the underlying genetic and physiological factors to create specific body parts and anatomical systems. Humans already have millions of years of evolutionary history that has given us our nimble fingers, mostly hairless bodies, and giant brains — to name a few things. All sorts of useful traits but not a single instance of functional wings.

“From an evolutionary standpoint, we don’t really see new structures developing from nothing; you generally must modify existing bones to produce a particular anatomy. For wings, this involves giving up arms or hands,” Blackiston explained.

If you think about it, this makes a lot of sense. No animal, extant or extinct, has the four-legged, two-winged structure of a western-style dragon. Blackiston suggests that this is because natural selection would be hard-pressed to create wings from shoulder blades.

If they existed, “dragons would likely look more like pterosaurs, where the arm bones and fingers elongate and are covered with a membrane,” he added.

The other problem with growing wings is that even with all the advances in genetic technology, it would be really difficult to edit genes in every one of the million cells in an adult. Instead, the blueprints for a set of wings would have to be inserted into the genome at the single-cell stage. So if you are reading this, it’s probably too late for you already.

Fine. If genetic technology can’t pave the way to a feathered future, maybe plastic surgery can? After all, it has managed to give people horns, forked tongues, and pointy fae ears.

Joe Rosen, a plastic surgeon at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Centre, believes that one day you could walk into his clinic and leave with a fresh pair of wings a few hours later. According to his blueprints, the wings would be grafted onto the back or moulded out of the existing flesh and bone, a grotesque-sounding process with angelic results.

“If I were to give you wings, you would develop, literally, a winged brain,” shared Rosen, in an interview with The Guardian. “Our bodies change our brains, and our brains are infinitely mouldable,” he added.

This means that the new appendages would soon get linked to the body’s nervous system, allowing the owner to feel as if they were always there. However, he did clarify that the wings would be just for the aesthetic.

That may seem like another dead-end to this flight of fancy, but the possibility of wings with sensation does show some promise. Say, all the stars align perfectly: we are able to advance the technology enough, we’ve sorted out the ethics of it all, and your far-sighted parents wanted an angel baby. Et voilà, you’re born with a pair of wings sprouting out your back. Ones that you can feel and control. Functional wings. Magnificent wings.

Could you fly then?

Think about the simplest mechanism of passive flight: gliding, or what Buzz Lightyear would call “falling with style.” The typical hang-glider needs a parachute that’s around 30–40 feet wide, just to let us gently descend through air. To be able to gain altitude, your wings would have to generate enough upward force to overcome the gravity pulling you downwards.

Birds do this by either flapping tiny wings really fast,like hummingbirds do, or massive wings really slowly, like pelicans. Either mechanism requires extremely strong muscles, which is something we lack.

Evolutionary change has honed birds to be perfect flying machines. Birds lack teeth, large brains, and complex digestive systems, all to minimize weight. They have massive, dense chest muscles to power their wide wings. Their bones are hollow but rigid enough to withstand the large amounts of force the wings produce. Every aspect of their biology is adapted to make them powerful but at the same time light as a feather.

On the other hand, we are substantially larger while being embarrassingly weak. To compensate for weight, the average adult male would need wings that are seven metres wide! Aside from looking ridiculous, wings that large would be heavy, so we’d need stronger muscles that would add more weight. Now we need even wider wings, adding even more weight. The solution in turn makes the problem more difficult to solve.

“We would have to drastically redesign the human body for flight to be possible, to the point that you would likely no longer be recognized as human,” Blackiston said. “It’s one of those ideas that always captures the imagination but is challenging to actualize in reality.”

A resounding no on the ‘wings of flesh and bone’ idea then. That’s okay, we’ve got technology in our arsenal, too.

The case for technology

Icarus didn’t grow his wings and neither did the Vulture from Spider-Man: Homecoming. We humans may not have hollow bones or massive muscles, but our claim to fame has always been our ingenuity, our use of tools.

Flight is very much possible through technology, and we’ve proven this fact multiple times. We’ve built planes that can carry hundreds of people over thousands of kilometres, jets that achieve speeds of over 3,200 kilometres per hour, and rockets that are strong enough to completely overcome Earth’s gravity.

Heck, we’ve even built some prototype jetpacks that eliminate the need for wings entirely.

All of these are incredible feats, yes, but they just aren’t good enough. Flying in an aeroplane is just like riding in a bus; great for going from point A to point B, but that’s it. There’s no air rushing past you, no action, no adrenaline.

Propellers and engines are bulky, noisy, costly, and dangerous. There are also a lot of regulations and requirements that you need to satisfy regardless of if you’re flying a recreational, ultra-light aircraft or a big passenger plane. Although aviation is possible through technology, it is inaccessible to the common man and unenjoyable for the trained pilot.

Through biology, we can grow wings that look the part. Through technology, we can build machines that do the job. At the intersection of both stands Hugh Herr on his cyborg legs, guiding us towards a winged future.

Herr is an MIT professor who lost both his legs in a mountain climbing accident. Undeterred, he built himself new ones: extremely high tech, prosthetic limbs with sensors, microprocessors, and actuators that returned his ability to walk, run, and skip.

Now, he is working on developing the field of neuro-embodied design, a new methodology of designing synthetics that works alongside biology. It aims to strengthen the bi-directional connection between the two, allowing us to not only control but also communicate with technology.

If you close your eyes and move your arm, you still know which way it is pointing, just via muscular cues. Neuro-embodied design would allow us to have that same sort of bodily awareness, but for robotic limbs. In a perfect synergy of mind and matter, the synthetic would become an extension of us.

So far, this growing field has yielded robotic limbs and surgical techniques that, when used together, give amputees the experience of having real limbs again. One such limb replacement even allowed a man named Jim Eqing to become the first cyborg mountain climber.

Imagine a future where the lines between man and machine are blurred even more. What if, instead of just restoring human capabilities, we could enhance them?

In his 2018 TED Talk, Herr said, “In this twenty-first century, designers will extend the nervous system into powerfully strong exoskeletons that humans can control and feel with our minds. Muscles within the body can be reconfigured for the control of powerful motors… In this twenty-first century, I believe humans will become superheroes.”

The wings we grow could be augmented with computers and motors to provide the power and control that we couldn’t, yet they would be a part of us, a mere thought away from unfurling.

Near the end of his optimistic speech Herr promises, “Humanity will take flight, and soar.”

It’s a wild thought, isn’t it? Something right out of a sci-fi movie. Imagine a world where wings are so increasingly commonplace that not having them becomes a handicap of sorts. If enough people chose to bio-augment in this way, our architecture, our cities would change entirely. New laws and regulations would have to come into place. Our current roads might be replaced by highways in the sky.

Everything will be altered to facilitate flight, to accommodate our new abilities. Would this change in infrastructure and our way of life put those that chose to be without wings at a disadvantage? What if they don’t have a choice, and the technology just isn’t accessible to them?

An ethical dilemma

Just as with genetic modification, the ethical dilemma stands: Should we give people wings?

We use tools to enhance our natural capabilities all the time. We wear flippers to swim faster, glasses to see clearer, shoes to run faster, and jackets to keep warm. But we have never attempted to alter our bodies directly for these effects.

Although this concept of using bio-augmentation would intrigue a lot of people, it would bring in a much larger number of skeptics. After all, not everyone wants wings.

In an interview with The Varsity, Darek Magusiak, a paragliding enthusiast and certified instructor, shared details of his experience in the air.

As someone who has been flying planes and gliders since 1996, he’s as close to a man with wings as we can find today. I asked him to describe the indescribable feeling of flight for us land-dwellers, and with immense glee in his voice, he narrated instances of flying beside crows and swimming through the clouds.

Magusiak described flying as a source of freedom. Beyond the thrill of successfully taking off with the wind, for Magusiak, flying brings a sense of peace which can be incredibly stress relieving.

He describes the silence — how “the only sound you have around you is essentially the sound of wind, the airflow, hitting your lights.”

I wanted to get his professional opinion on this novel concept of bio-technological wings. At first, he was taken aback by the idea but soon warmed up to it.

While Magusiak believes it would take a lot to “develop it to the point it was viable,” he is excited about it, even if he’ll be “too old for it” by the time it comes out.

After hearing his thoughts, I conducted an informal study: for a week, I asked everyone I met whether they’d be open to getting wings in this way. Most said yes, with some even describing vivid dreams of flight they’d had since childhood.

However, not everyone was as enthusiastic about the possibility. Some had an outright negative response, saying, “I would never alter my body in that way.” Others wondered whether the procedure was permanent and stated that they’d go for it only after spending half their lives on the ground. A few people started discussing the ramifications of living flightless in a winged world, ultimately saying that they’d have no choice but to get them.

What about you? If you had the access to wings of flesh and steel, would you choose to fly? Would you give in to that call of the void or miss out, stay standing on your own two feet?