U of T is a university of many different architectural styles, from brutalist to neoclassical to Romanesque. One of the most majestic styles of architecture present at U of T is Gothic architecture: a form developed in the later Middle Ages and characterized by large windows, arches, and, most recognizably, flying buttresses.

The flying buttress is a thin half arch that connects a wall to a culée, a large column that helps the wall support the weight of its roof. The flying buttress allows walls to be thinner while still preserving a high ceiling, and enables the inclusion of large windows that illuminate the interior of the building. This contrasts with the earlier medieval style of Romanesque architecture, which often features thick walls with smaller windows punched in.

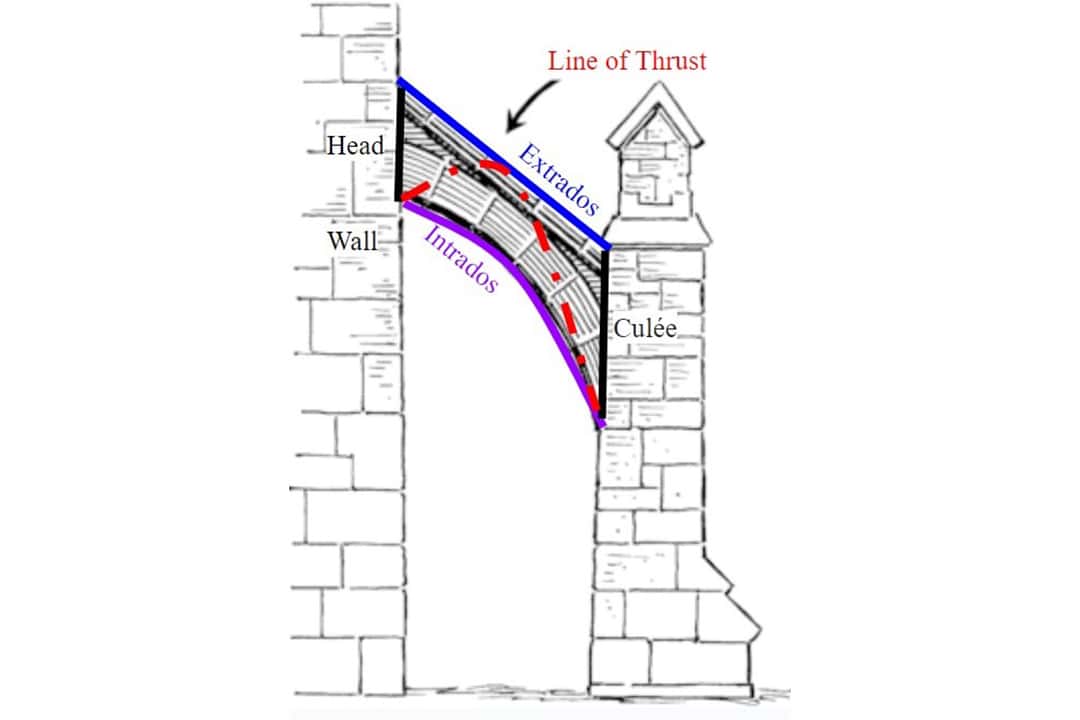

The amazing feature of the flying buttress is its ability to support much of the walls’ weight while still being thin and graceful. To do this, flying buttresses have a few important components. The ‘head’ of the buttress is where it connects to the wall it is supporting. The ‘extrados’ is the straight line of the top of the buttress, and the ‘intrados’ is the line of the circular arc on the inner side of the buttress.

As shown in the figure below, these elements mediate the buttress’ line of thrust, which shows how the forces from the wall are directed through the buttress and toward the ground. The way in which the wall’s weight is redirected to the ground is similar to how electricity from a lightning strike would move through a lightning rod toward the ground and become grounded.

Flying buttresses thereby balance the bulk and greater stability of a thicker buttress and the elegance and grace of a thinner buttress.

Flying buttress’ failures

Theoretically, in the physics of a flying buttress, the gravitational force along the buttress pulling the wall toward the ground should apply enough horizontal pressure to keep the stones of the buttress together. However, when there is too much vertical thrust and not enough horizontal thrust where the buttress connects to the wall, “sliding failure” can occur.

Sliding failure — in which the intrados’ stones near the head of the buttress overcome friction and slide against each other — is the most likely type of failure for a buttress. When the sliding motion travels upward in the masonry, it creates cracks in the flying buttress, leading to its collapse.

Another type of failure that flying buttresses can be met with is when the force carried outward through the buttress is directed more horizontally than vertically at its base, which can mean it pushes out at the culée, rather than down, and overturns it.

Thus, the stability of the buttress largely depends on the ‘head’ of the buttress receiving an overall horizontal thrust and the culée receiving a vertical thrust.

Maximizing flying buttress’ stability

Several factors — like the steepness of the buttress, and whether the centre of the arc described by the intrados is inside or outside of the wall — can maximize the head and the culée receiving the appropriate amounts of thrust in the right directions.

When the centre of the partial circle formed by the arc of the intrados is inside of the wall, the buttress is more stable. This orientation of the arc guides horizontal thrust from the wall into the buttress, preventing sliding failures, and guides vertical thrust to the culée. Even when the intrados arc is shorter than ideal, locating the centre inside of the wall can help stabilize an otherwise tenuous buttress.

Furthermore, steeper buttresses play an important role in guiding vertical thrust and effectively offloading thrust onto the culée. Steeper flying buttresses also often mean the centre of their intrados’ arcs is inside of the wall.

The flying buttress is emblematic of Gothic architecture, showcasing the delicate balance between form and function that builders in the Middle Ages maneuvered to create airy and soaring buildings while ensuring lasting stability.

Many gothic buildings at U of T, such as Hart House, Burwash Hall, and Knox College, do not contain flying buttresses, but they do still showcase the majestic style of Gothic architecture that flying buttresses enabled, inspiring awe even today. And, if you look carefully at some buildings like Trinity College, there are small flying buttresses just waiting to be discovered by you.

No comments to display.