This past winter break was the first time I’d been home since coming to college. In my first hours at home, I was filled with a sense of familiar calm — but soon, I was filled with the irrepressible sensation of being stuck and suffocated in the suburbs. When I got back, walking out of College subway station and onto the lively glowing street was a breath of fresh air. Still, I can’t say the same for a lot of buildings at U of T.

Circumstance has an undeniably profound impact on mental health. A collection of studies shows that exposure to the environment — through factors such as urbanicity, the degree to which a geographical area is considered urban; housing conditions; and access to green space — have wide-ranging impacts on mental health. In particular, a 2023 study in the journal European Psychiatry summarized findings on the impact of architecture, concluding that “incorporating elements such as natural lighting, open floor plans, private and open community spaces, artwork, safety procedures, and nature/views of nature, provides a supportive environment for the mental well-being and the treatment of mental disorders.”

Considering students spend a vast majority of their time on campus — or at least a substantial amount, in the case of commuters — I believe the onus then lies with U of T to take conscious action in their design to ensure student well-being.

Architecture at U of T

An examination of one of UTSG’s flagship buildings, Robarts Library, can reveal the current state of affairs at U of T. Hailed as a “brutalist masterpiece” by the Canadian architecture magazine Spacing, Robarts is undeniably the heart of campus, with up to 18,000 students passing through each day. As Robarts holds such central status in campus life, it should, at the bare minimum, be a pleasant experience to look at, if not perfectly designed for student well-being.

Robarts sadly fails this bar in the public’s view, having been nominated by readers of the Toronto Star for the “worst building in the city.”

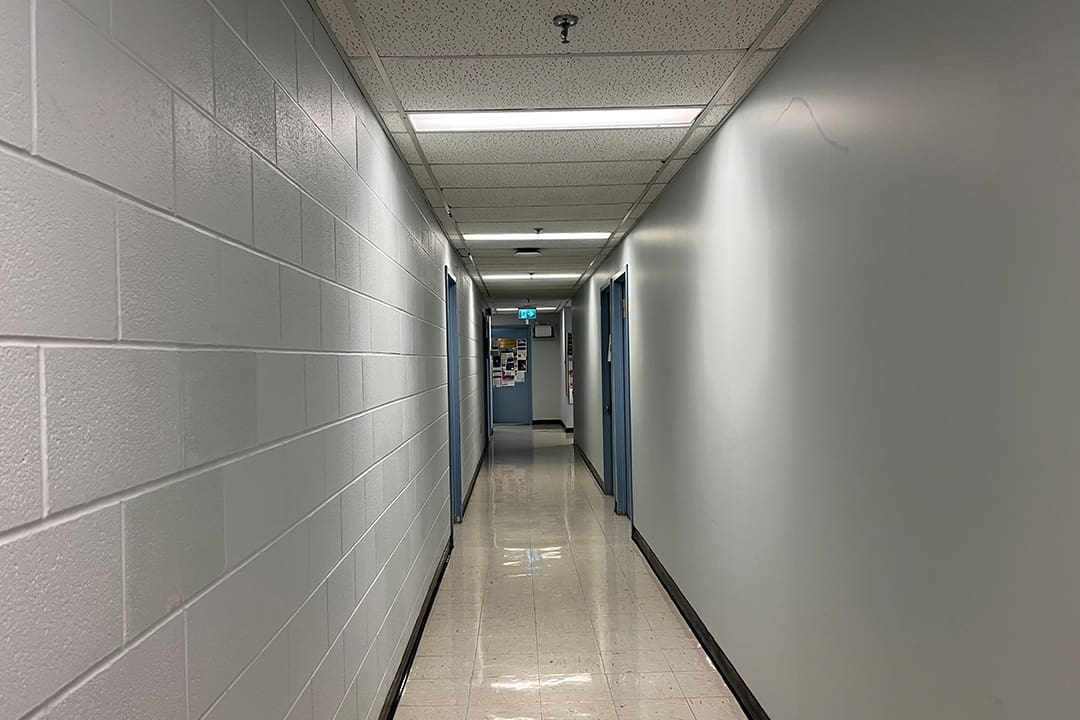

Beyond Robarts, U of T classrooms are no better at providing inspiring spaces. Most notably, most STEM buildings, especially those for the Faculty of Engineering, provide depressing, grayscale environments. Students, especially engineering students — most of whom have approximately 25–30 hours of instruction a week in their first year — are trapped in those environments for most of their productive hours.

Researchers from Central Michigan University showed that, in a work environment, exposure to the natural environment — in particular, sunlight — resulted in both physical and psychological improvement among subjects. But nearly every engineering building I’ve walked through has been a maze of dull tones and minimal windows, with dim, dreary lighting.

Of course, this is not a shortcoming only embodied in engineering buildings, as most older buildings suffer from the same monotonicity and lack of natural light.

How U of T can do better — and what it’s doing

Buildings don’t spring up overnight, but U of T’s recent and current building projects look very promising to me. Recent renovations and newer buildings include Robarts Commons, the gleaming five-storey attachment to the main library with a wall of windows and no shortage of natural light.

The university is also planning many new buildings and expansions. Notably, two months ago, U of T broke ground on an expansion to Lash Miller Chemical Laboratories. Renderings of the expansion display a focus on natural light and open spaces. Other new projects include the Spadina-Sussex Student Residence, which I consider an important step to keeping up with the competitive housing market in Toronto and well planned for student well-being with plenty of sunshine.

U of T is also planning what I see as its most ambitious project: the construction of a new Academic Tower behind the Munk School of Global Affairs. Proposed as “an iconic, precedent-setting building” designed to be Canada’s tallest academic wooden building, the glass-lined tower projects a commitment to sustainability and student well-being through conscious architecture. U of T is also planning the pedestrianization of another street through its Willcocks Commons project, providing space for more green spaces.

Finally, some of the areas in U of T’s massive Landmark Project are in their final stages, with renovations around King’s College Circle showing a clear dedication to promoting green spaces and an increased focus on pedestrians. In particular, I had the pleasure of walking through a small, half-finished garden in construction near University College. Even in the dead of night with tarps of dirt scattered around, I could see a bright future ahead.

I believe U of T is doing its best in many ways. For a university that predates its country, the buildings have aged functionally well, and the university is providing ample effort to update and renovate as our understanding of architecture and well-being evolves. To me, it seems that the clear vision of creating spaces with more natural light and greenery shows U of T’s understanding of how urban design affects mental health and a commitment to providing the best experience for students.

Max Zhang is a first-year student at Woodsworth College, studying computer science. He is the Mental Health columnist for The Varsity’s Comment section.