In March last year, on an early Monday morning, I was walking back to my residence from Robarts when I saw three men seeking shelter together on an air vent in front of a University Health Network (UHN) building. It was cold, and they’d clearly been trying to stay warm by tying a blanket over the vent, in order to contain the marginal warmth emanating from it. A few years ago, that same vent was the subject of controversy when the UHN installed an uncomfortable, spiny metallic grate over it — a textbook example of hostile architecture.

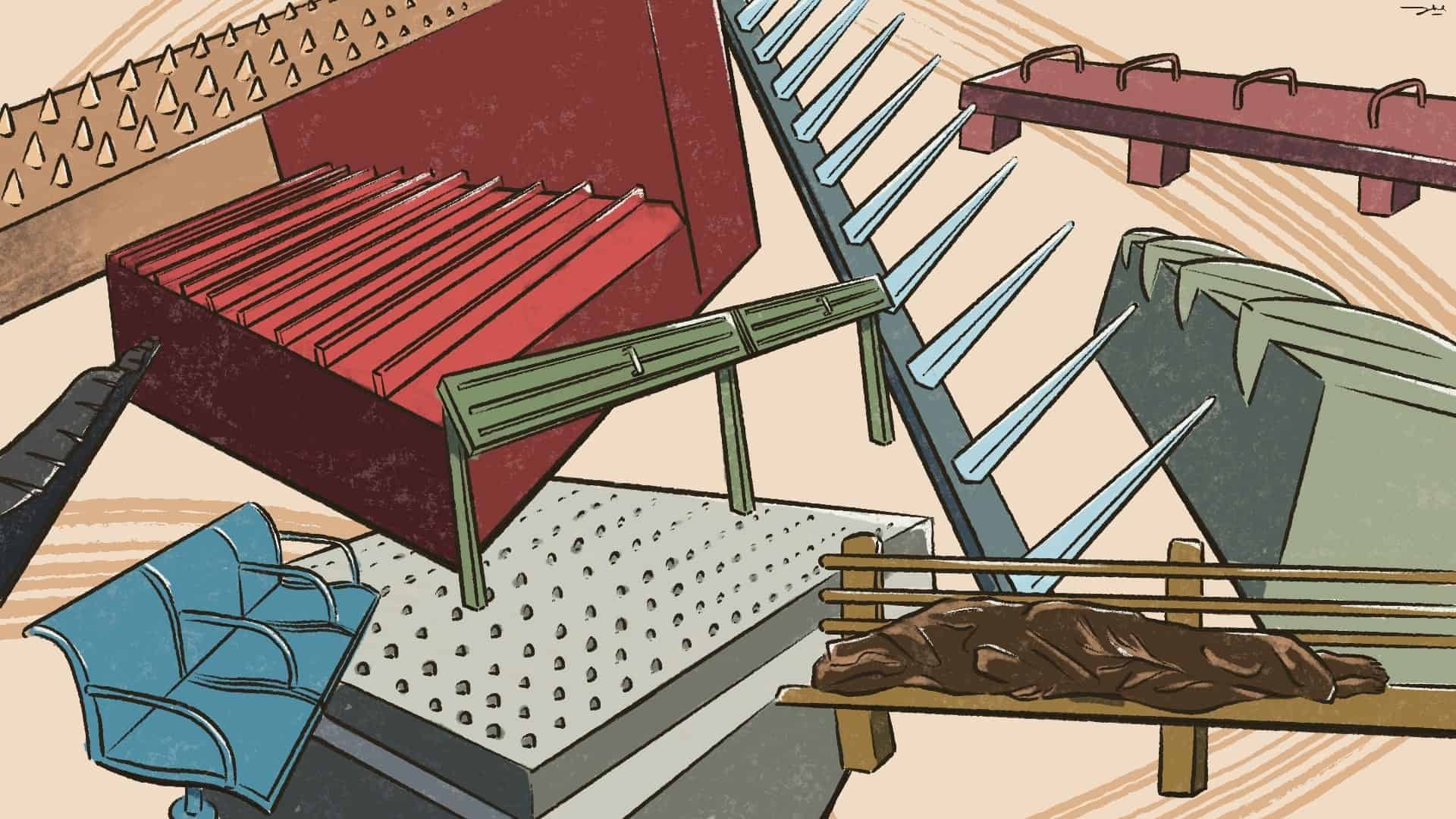

Hostile architecture is an urban design strategy intended to influence public and pedestrian behaviour, with strategies such as concrete notches on a curb to prevent people from skateboarding along it or metal grates used to block air vents. While hostile architecture is often proposed as a way to ensure public safety and accessibility, more often than not, it’s a way to keep people experiencing homelessness out of public spaces.

Hostile architecture is ubiquitous in Toronto and many other major cities around the world. Whether you were aware of it or not, you have probably seen hostile architecture around the city.

For one, it is often disguised as architectural design choices or even art. In her thesis An Uncomfortable City, University of Victoria alum Jessica Annan discussed how cities use statues to block certain areas from public access. Her thesis contained an image of metal silhouettes placed on heating vents, occupying a space now inaccessible to those who could have sought warmth there.

Altogether, this hostile architecture makes Toronto a less welcoming — and more dehumanizing — city.

Hostile architecture is also sometimes hidden under the guise of disability accommodation. Last year, in Galway, Ireland, a city councillor proposed a plan to place benches around the city that feature a hole in the centre — preventing people from lying down on them — and argued that this design was intended to promote wheelchair accessibility. This design faced criticism from wheelchair users themselves, who argued that such benches were only hostile architecture thinly veiled as an accommodation.

It is important to know what hostile architecture is and be able to recognize it around UTSG and downtown Toronto. Extra armrests in the middle of benches, the spikes on the sidewalks, and the bars over the vents are highly visible to the public eye. Altogether, this hostile architecture makes Toronto a less welcoming — and more dehumanizing — city.

How hostile architecture makes it worse

Anika Rosen, an undergraduate student at Trent University studying sociology, investigated how hostile architecture prevents people experiencing homelessness from occupying public spaces. Rosen writes that it does this by physically restricting the unhoused from using objects in public spaces outside of their intended purpose. For example, adding dividers between seats on a park bench restricts the public to using the bench for sitting only.

Rosen’s research reveals a widespread notion among the public that homelessness is “inherently disruptive and unsightly,” and that pushing them out of these spaces was justified. Rosen writes that this notion is exacerbated by “anti-homeless policies” creating a perception of criminality toward homelessness. Public indecency laws and building policies can paint necessary actions such as bathing as illegal, when done in spaces deemed public. A 2015 study in Frontiers in Psychology echoes Rosen’s findings. The study found that people experiencing homelessness faced stigma and judgment, which impacted the way others treated them.

In its most recent study, the Centre for Homelessness Impact noted the importance of understanding how “unconscious forces and biases” impact public perception of homelessness. Misconceptions — such as ideas about the prevalence of substance abuse among the unhoused, and misestimations of the percentage of our population experiencing homelessness — create an environment of hostility towards people experiencing homelessness.

Rather than challenge these misconceptions, hostile architecture reinforces them by framing certain actions that are commonly associated with homelessness — such as sleeping in public — as abnormal and disrespectful. By treating homelessness as something that should be hidden from the public eye, city councillors fall short of focusing on solutions that will benefit both the people experiencing homelessness and community wellness.

On the other hand, preventing homelessness requires long-term solutions supported by research, such as affordable and supportive housing and easy access to physical and mental health care, including substance use programs. A 2021 paper in The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health discussed how many of those experiencing chronic homelessness cannot afford housing due to health issues, which are then further exacerbated by lacking housing security. To simultaneously address both issues, we must make mental and physical health care readily available and free to access for everyone.

By treating homelessness as something that should be hidden from the public eye, city councillors fall short of focusing on solutions that will benefit both the people experiencing homelessness and community wellness.

According to the City of Toronto, the leading cause of death among people experiencing homelessness is drug toxicity. Harm reduction workers around Toronto have outspokenly advocated for more funding for supervised consumption sites, where people can use drugs in a monitored environment.

Many research papers have demonstrated a need for more funding for social services, health care policies, and substance use programs, which could be implemented to improve the quality of life for people experiencing homelessness. Unlike hostile architecture, these programs can actually address problems caused by homelessness, rather than simply hide it.

Part of a vicious system

Sometimes, a public bench or vent is the only place to go for rest, but hostile architecture makes even these spaces inaccessible, and in doing so, removes any prospect of feasible shelter — becoming the final step in making this city unlivable.

This isn’t just about a bench; it reflects a cycle that leaves people experiencing homelessness vulnerable to harsh weather conditions without a guarantee of physical safety. There are currently over 10,000 unhoused people in Toronto, and the Toronto City Council has declared homelessness an emergency.

Toronto’s cost of living is unattainable for many, so many people move out of or are evicted from their property. Shelters are overcrowded and do not receive enough funding to provide proper security or support to their residents living there. Encampments often get shut down. Finally, hostile architecture removes the simplest of options: a bench.

Toronto’s infrastructure has not been set up to support low-income households, and instead seems to cater consistently to the wealthy. This makes it difficult for many to afford the city’s high cost of living. In its December 2023 report, the online real estate renting platform Rentals.ca stated that the average asking price on monthly rent for a one-bedroom Toronto apartment in November was $2,601.

Meanwhile, the 2006 and 2016 censuses conducted by Statistics Canada show that, between 2006 and 2016, there was about a 36 per cent decrease in the number of Toronto properties for which current renters were paying under $1,000. At the same time, there was about a 323 per cent increase in the number of units that cost renters over $1,500 per month.

Inflation has also disproportionately impacted students. In 2019, Covenant House Toronto, which is part of a chain of homeless shelters in major cities across Canada, reported that 26 per cent of its residents were students — and Covenant House Toronto is only one of many shelters across the city that support those experiencing homelessness.

The City of Toronto defines shelters as facilities that provide people experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity to sleep, while also providing essential services including laundry, meals, and physical and mental health care. In recent years, the city has shut down several temporary shelters around Toronto it had set up during the height of the pandemic. In January 2023, CTV News reported that the city planned to close five shelters over the year, which — according to a report made by city staff — was intended to facilitate a transition away from temporary shelters and towards more long-term solutions to housing security.

Hostile architecture serves as a way for us to avoid confronting the root causes of homelessness, and we cannot allow it to be overlooked and accepted as a permanent staple of our cities.

Yet the same report admitted that closing these shelters could pose significant damage to those who relied on their services. The lack of affordable housing to replace the closing shelters, accompanied by an increasing proportion of Toronto’s population experiencing homelessness, has contributed to space shortages in shelters that are still open. According to a CBC News article published in July 2023, shelters for people experiencing homelessness in Toronto turned away 273 people a night on average in the month of June.

Even those who can secure a spot in shelters often prefer not to stay there for long. Many people who’ve spent time in shelters report thefts and violence, creating a difficult living situation that some people experiencing homelessness avoid, despite the dangers of sleeping outside, especially in the winter months. According to the Toronto Star, some people seeking shelter who looked to tent encampments did so due to safety concerns and shelter overcrowding — but the Toronto Police Service frequently evicts encampment residents.

So what’s next?

Hostile architecture does not address any of the root causes or contributing factors of homelessness. Instead, it targets people who have been beaten down by the system and further ostracizes them by preventing them from existing in public spaces. Hostile architecture serves as a way for us to avoid confronting the root causes of homelessness, and we cannot allow it to be overlooked and accepted as a permanent staple of our cities.

Many community members have taken it into their own hands to catalogue instances of hostile architecture to demonstrate how common it has become and to show people how to identify it when it has been disguised. An example of this is DefensiveTO, a website created in 2019, which allows anyone to upload photos and locations of hostile architecture in downtown Toronto. For an audience outside Toronto, there is also r/HostileArchitecture, a popular subreddit dedicated to sharing examples of hostile architecture worldwide.

Anger has great power when it is used properly and is directed at the right people.

The bars covering the air vent in front of the hospital — the only source of warmth for the men I saw that early morning — were only removed after community members wrote, called, and emailed the administrators who were responsible until they uncovered them.

Anger has great power when it is used properly and is directed at the right people. For example, by emailing the office of Toronto’s mayor, Olivia Chow; University–Rosedale’s member of provincial parliament, Jessica Bell; or the premier himself, Doug Ford. This reaffirms that U of T students are members of the downtown Toronto community, and have an invaluable voice to contribute to local politics. Tell these politicians that you do not support hostile architecture in Toronto, and ask them to fund researched solutions instead, such as supportive housing arrangements and free mental health care.

To end homelessness, and improve the quality of life for everyone in our community, we must not look away — but look forward to a better Toronto for everyone.

No comments to display.