This is the second part in a three-part investigation by The Varsity into international students’ financial struggles at U of T.

Akaash bought a mechanical bike in the summer of 2021. Instead of using it solely for transportation or leisure, he decided to start delivering food for UberEats.

Getting a job as an international student is difficult. Study permits only allow international students to work up to 20 hours per week during the academic year, but their domestic counterparts face no restrictions. “A lot of places don’t hire us [because] they know we are only allowed to work part-time,” he said.

While he enjoyed biking and exploring Toronto through his UberEats job, sometimes he got paid below minimum wage. If customers chose not to tip, he would only be left with $4 for biking six to seven kilometers. At times, his hourly wage was as low as $10 an hour.

Akaash says that many of the people he worked with at UberEats were international students who were people of colour.

Other jobs Akaash has worked were downright unsafe. In December, Akaash took a construction job in Burlington. He and the crew dug through the concrete ground of a restaurant in order to replace its grease trap, even though he had never used a jackhammer before. “There wasn’t a lot of safety being followed… when you’re using the jackhammer, there’s stuff flying all over the place. I didn’t have safety glasses,” he recalled.

He got paid in cash.

“Especially through the pandemic, we’ve seen that it was migrant workers who were stocking shelves overnight in grocery stores, handling packages in warehouses, cleaning offices and buildings, working in food service, and making deliveries through the cold and snow. It was current and former international students who were doing this,” says Rho. She explained that many international students are forced to work in such risky conditions in order to pay for their high tuition fees.

Of course, not all international students work precarious jobs — but most of them work out of necessity, which adds an additional layer of stress to their lives. Aliya Ali Shaikha, a second-year international student from the United Arab Emirates (UAE), had to work for her father’s business in her first year at U of T, occupying her during the day. “By the time nightfall would come, I’d be really tired and I wouldn’t be able to focus on my studies,” Aliya says.

Even though Aliya was awarded a scholarship that reduced her tuition to $15,000 a year, she says that cost is still a huge strain on her family. She has four other siblings, and her father’s business has been incurring losses. In 2016, the UAE faced a market crash, which left her father in “millions and millions of dirhams” of debt.

“I never involved myself in any extracurriculars, competitions, or anything like that in my first year,” Aliya says. “What’s the point of extracurricular activities… when I need to help my dad?”

Some international students persevere, hoping to find better paid work after graduation with a three-year post-graduation work permit. But this hope is not always rewarded — in fact, the precarity and stress experienced by students can continue into working life.

According to a 2021 Statistics Canada study, international students actually earn less than their domestic counterparts post-graduation and experience lower employment outcomes. Factors that contribute to this include employers’ reluctance to hire applicants with temporary residency status and shorter pre-graduation work experience in the country. The study also indicates that because they are relatively new to the country, international students have a shorter amount of time to build local networks.

International students’ temporary residence status also renders them especially vulnerable to exploitation. In her research, U of T professor Patricia Landolt, who studies state migration management systems, found that people with precarious legal status like international students experience more vulnerabilities at work, in housing, and in access to health care. Yet, they continue to tolerate these poor conditions in order to fulfill the work requirements needed for permanent residency.

“As an immigration system, we’re using students as a kind of filter system for recruiting the world’s best and brightest, right? That system is really awkward, costly, cumbersome, and risky. And those risks fall on the students — not on the institutions that recruited them, not on the federal government,” Landolt says.

A history of international tuition at U of T

International tuition fees weren’t always this exorbitant. Prior to 1977, domestic and international tuition fees in Canadian universities were the same.

After World War II, many countries felt a sense of responsibility for human well-being beyond their borders. Canada took an active role in global humanitarian affairs and increased its foreign aid presence in the Global South. Part of Canada’s foreign aid took the form of educational opportunities for international students — policymakers viewed international students as key players in building good economic and political relations with other countries.

Then, Canada faced an economic crisis in the 1970s. As the country plunged into an economic landscape of worsened inflation, declining profit rates, and growing unemployment, policymakers’ attitude toward higher education turned sour. They began to see postsecondary institutions as bubbles of luxury and a public burden. “I somehow sense,” the Ontario Minister of University Affairs declared in 1970, “that we haven’t really used our dollars [in higher education spending] in the most effective ways.”

Public opinion swayed in the same direction. A Gallup poll from 1971 found that 49 per cent of Canadians felt that public spending on higher education was too high. This number was only at seven per cent in 1965.

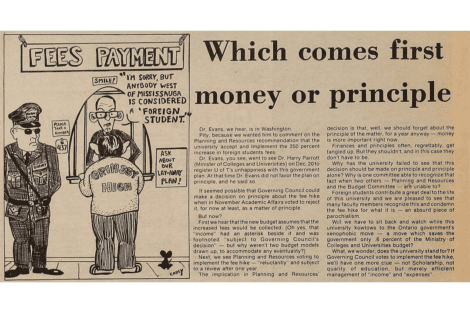

The turning point for international tuition came in May 1976. Ontario’s Minister of Colleges and Universities, Harry Parrott, wanted to save money. So, he made a decision — the Ontario government would decrease their subsidies to international students. As a result, individual universities had to decide whether to pass the fees incurred by this move to international students — thus increasing international tuition by 2.5 times — or to shift their overall budgets.

Parrott’s move was met with widespread opposition. Many pointed out that because international students in Ontario were so few, the Ministry of Colleges and Universities was only going to save 0.6 per cent of its budget by eradicating financial support for them. The Ontario Federation of Students called the policy reflective of the “government’s political desire to [crack down] on foreigners,” as it targetted the most visible population on university campuses in order to save a negligible amount of money.

John Evans, U of T’s president at the time, said, “We must always recognize the legitimate public concern about how we use public resources, but this does not mean we should be affected by our society’s current attack of xenophobia.” The Black Student Union at U of T called the hikes “an obsolete form of chauvinism.” Others bluntly described the policy as “discriminatory” and “racist.”

But, ultimately, nine out of the 15 universities in Ontario chose to pass the fees to international students. U of T was one of them.

THE VARSITY

On March 17, 1977, the Governing Council — the highest democratic decision-making body at U of T — voted to increase international tuition fees. In the following year, undergraduate international tuition rose from $630 to $1,950 per year, while domestic tuition increased only slightly, from $630 to $670. Differential fees had now been established in Canada for the first time.

In June 1994, the Ontario government excluded international students from OHIP coverage. While international students once had the same access to the health care system as Ontario residents, they now had to look to private insurance schemes for coverage. Currently, international students are still not eligible for OSAP. Then, in 1996, Ontario deregulated international tuition fees, which meant that institutions could now set tuition fee rates at whatever level they wanted.

With all these mechanisms in place, the government and universities could now mine international students for cash. According to a report from Higher Education Strategy Associates, international students now supply nearly $7 billion directly to Canadian postsecondary institutions each year — essentially propping up Canada’s higher education system. Out of that $7 billion, almost $1.4 billion comes from the pockets of U of T’s international students.

Decreasing government funds, increasing international tuition

As protections for international students eroded in the past few decades, the Ontario government consistently decreased its base funding to postsecondary institutions. According to the Progressive Conservative government’s 2019 budget report, these decreases are meant to hold postsecondary institutions to account in providing “positive economic outcomes.”

Government operating grants — the main source of funding provided by the provincial government — made up 33 per cent of U of T’s revenue in 2005. This dropped to just 18.1 per cent in 2021. Accordingly, U of T’s budget now has the lowest proportion of government funding among Canadian universities.

To try to fill these gaps in funding, public universities have turned to other means for generating income, the easiest of which is to increase international tuition, which remains unregulated. From 2005 to 2021, the undergraduate international tuition of students at the FAS, UTM, and UTSC has increased by 264 per cent. Undergraduate domestic tuition has increased by 46 per cent in the same timeframe.

Increasing international student enrolment is also a popular option. In 2005, international students comprised only nine per cent of U of T’s student population. By 2020, that number had risen to 26.8 per cent.

In the 2017–2018 academic year, international tuition fees became U of T’s largest source of revenue for the first time. This pattern continues today. The university’s 2022–2023 budget predicts that 43 per cent of operating revenue will come from international tuition.

The trend in Ontario of relying on international tuition fees for operating costs has consequences. Now, without international students’ cash, public universities in Ontario could be in danger of folding.

This is exactly what happened to Laurentian University in 2021. “Laurentian University collapsed because international students didn’t come,” Landolt says. Many other commentators have also pointed to Laurentian’s international student shortfalls as a leading cause for why it declared insolvency.

Crucially, the majority of U of T’s international tuition fees come from the Global South. In 2020, 10 out of U of T’s top 15 source countries for international undergraduates were in the Global South. These 10 countries alone made up 78 per cent of undergraduate international students at U of T.

One of these countries is Indonesia, where Arthur is from. Even though he was awarded scholarships that have reduced his tuition to around $10,000 a year, he says that his family still struggles to pay the remaining amount. “[It’s] mainly because I come from a middle-class family in Indonesia, and Indonesia has one of the weakest currencies in the world,” he says. Indeed, as of March 2022, one Indonesian rupiah is equivalent to $0.000088.

Money from lower-income countries now makes up a significant portion of U of T’s revenue. In other words, the Global South is subsidizing a significant portion of U of T’s operations costs.

“Something is fundamentally wrong with claiming that we run a public higher education system that, in fact, has been deeply privatized and relies on international students for such a high proportion of fees,” says Landolt.

“What happened to the government funding for the university system that [got us] into this situation?”

Disclosure: Arthur Hamdani is a Varsity staff illustrator.