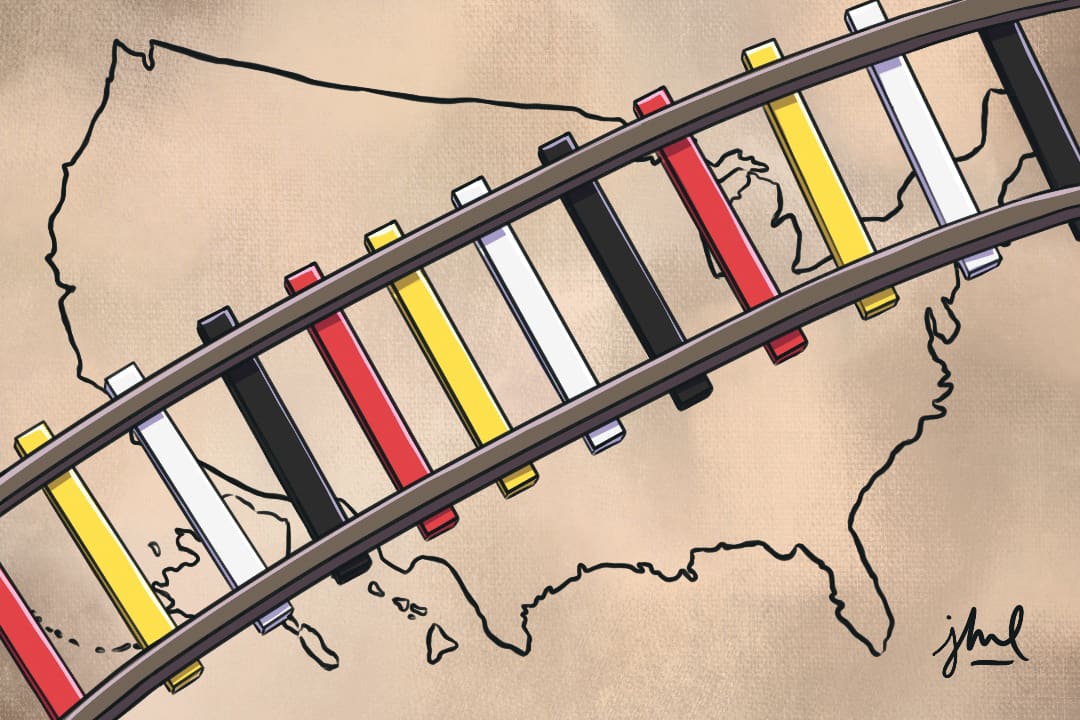

On March 21, U of T’s Asian Institute and the Centre for Indigenous Studies hosted a virtual discussion with author and Barnard College professor, Manu Karuka. During the talk, Karuka spoke about his book, Empire’s Tracks, which reframes the history surrounding the US transcontinental railway. The book explores the transcontinental railway’s relationship to Indigenous peoples — specifically, the Cheyenne, Lakota and Pawnee. Karuka draws connections between “Asian and Indigenous laborers, the land, industrial and finance capitalism, war, [and] sovereignty.”

At the beginning of the discussion, Karuka mentioned three distinct themes — “continental periods,” “countersovereignty,” and “modes of relationship” — which were the basis for his book.

Karuka explained that the identity of the United States is rooted in imperialism. “To conceive of the United States in national terms is to naturalize colonialism… There’s no national US political economy — only an imperial one which continues to be maintained,” he said. He added that his book focuses on how American history “has often [been reframed by colonizers] as a story about ‘cultural dominance.’ ”

Karuka said that the transcontinental railway could be used to “understand the history of North America in relation to the histories of Africa, Asia, [and] Latin America.” Through this understanding, Karuka added, we can see that “railroad construction in North America consistently anticipated historical patterns elsewhere in the colonized world.”

Within Empire’s Tracks, Karuka used this theme to demonstrate parallels between railroad networks in North America and South Asia. He connected the US railroad expansions to railroad systems in other countries that also displaced people to make room for avenues of commerce. “[Noticing these patterns] in different parts of the world could tell us a lot about how imperialism changed over time and what stayed the same,” he added.

The second theme Karuka highlighted was “countersovereignty.” Karuka coined this term to capture the US’ history of trampling over Indigenous peoples who had prior claims of sovereignty in order to assert its claim to be the rightful owner of their territories. He described it as an anxious, violent institutional response to “prior and ongoing collective Indigenous life.” In Karuka’s words: “Indigenous collective life and struggle are positioned as a core contradiction of US political economy.”

Karuka’s final theme, “modes of relationship,” related to philosopher Karl Marx’s analysis of capitalism. Marx believed that the relationship between capitalists and their workers was inherently exploitative.

Karuka does not only recognize the exploitative nature of capitalism, but he also highlighted how capitalism has to contend with “prior and ongoing modes of relationship” that already exist and are important to individual cultures, such as Indigenous cultures. Karuka further explained that his work was inspired by Indigenous feminists such as author Sarah Winnemucca and economist Winona LaDuke.

After Karuka explained his book’s main themes, six U of T graduate students described elements of Karuka’s writing that they admired. They also connected the book to their current research, all which related to colonialism. The students’ remarks emphasized the importance of “[remaining] deeply informed [when] studying Black studies and Indigenous studies,” and the importance of “[recognizing] migration as a part of US expansion for… continental imperialism.”

Thomas Blampied, a PhD candidate in the Department of History, highlighted that Karuka’s book wasn’t just about “irrelevant history” but also about topics that were applicable to Canada. Blampied explained that, similar to the transcontinental railway in the US, the Canadian Pacific Railway also benefited from “land grants, capital, and military protection.”

In his closing remarks, Karuka commented that individuals can rarely “claim mastery over fields like Black studies or Indigenous studies,” noting that anyone who chooses to study history or traditions must do so with humility.

However, Karuka noted that one positive element of studying Indigenous histories is that it allows us to “question who we are.” He noted that, in the twentieth century, we’re seeing “[a] slippage… between where [we] come from and the places where we find ourselves.” By learning about the struggles of Indigenous peoples, Karuka explained, we are taught a lesson about humility and get an opportunity to reaffirm our stance against imperialism.