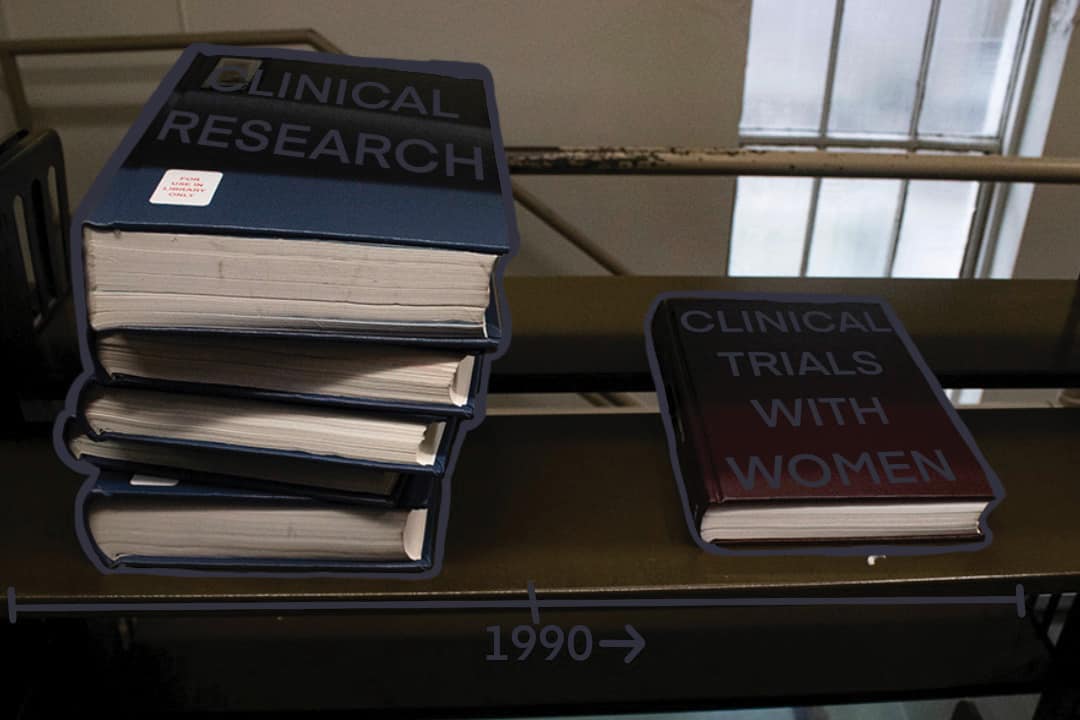

While clinical research and trials are the heart and soul of advancement in the medical field, they failed to sufficiently include women before the 1990s. The result has been a lack of knowledge about the interactions between biological sex, disease, and medication, which has become known as the ‘women’s health gap.’ This gap is also bigger than just cis women — how certain diseases affect transgender, intersex, and nonbinary people is even less researched.

However, examining the historical exclusion of women from clinical studies is a good first step.

Does sex matter?

Those who wish to defend the medical field’s ignorance may argue that women are equal to men, and therefore that treatment for all patients should be the same. However, the reality is more complicated: for example, at a cellular level, our biological sex affects how our bodies interact with disease and medication.

A study conducted by The Institute of Medicine in 2001 found that when it comes to running and analyzing studies in health-related research, sex matters. There are differences in the incidence and severity of diseases, as well as various cellular responses, depending on a patient’s sex. These distinctions can often be traced to reproductive hormones, but hormones aren’t the only reason for this variation. The fact that research has traditionally excluded anyone but cisgender men has led to women and everyone else receiving compromised medical care.

Creating the gap

Prior to the 1990s, white men were considered the ‘standard’ study population. Women were viewed as ‘too emotional’ — and, therefore, too risky as test subjects, because their hormones were considered irregular and unpredictable.

In many cases, women were banned from participating in clinical trials in order to ‘protect’ their ability to reproduce in the future. Organizations and medical groups focused on the one sex-related difference they were willing to admit, and, for years, women were considered reproductive vessels and nothing more.

In the twentieth century, the endocrine system was discovered. While it provided medical professionals with an obvious difference between bodies assigned male and female, they continued to believe that all other organs functioned the same regardless of sex. They used this discovery to blame any medical issues that seemed to disproportionately or specifically affect women on their hormones.

Change began in the 1990s, when it was found that participants in studies about diseases that affect everyone, such as heart disease, were disproportionately cis men. These findings brought to the surface the gap in research that had been building over the years: our understanding of how women’s bodies functioned and interacted with disease was severely lacking, if not missing altogether in some cases.

In 1992, the Food and Drug Administration stated that it was important for women to be included in clinical trials to understand how they respond to pharmaceutical agents. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act of 1993 required that all NIH-funded clinical trials must include women as participants.

Since then, there has been a significant increase in the inclusion of women in clinical trials, but not enough to make up for the years of their exclusion. Cumulative reviews from 2011 found that in the average trial, only 37 per cent of participants are women.

The difficulties of closing the gap

While these improvements have been made, we are still playing catch up on the centuries when women were absent from medical research. Since the 1990s, research on diseases that primarily affect women — such as breast cancer, cervical cancer, and cardiovascular disease — has made significant progress in including women in research studies and clinical trials. Of course, this progress does not mark the end of the gap — eight out of 10 prescription drugs taken off the market between 1997 and 2000 caused greater adverse side effects on women due to the male bias in clinical research during the development of these drugs.

Although many initiatives to increase the involvement of women in clinical trials have been introduced, women are still less likely to participate in them due to social and societal pressures and norms. Today, women have an increased burden of unpaid domestic labour. They spend, on average, twice the amount of time on unpaid work in comparison to men. As a result, women often have more family obligations than men, and it is more difficult for them to escape those obligations in order to partake in clinical trials.

Research facilities must go out of their way to make participation in clinical trials more accessible for women. This can include initiatives such as compensating childcare while subjects are actively participating in the clinical trials, as well as hiring women staff to increase the comfort of participants.

Women’s College Hospital — located at Bay and College just southeast of the University of Toronto’s St. George campus — has started the Women’s Cardiovascular Health Initiative, which is the first of its kind in Canada. It aims to help women who are struggling with heart or cardiovascular problems and provides a rehabilitation program designed with women in mind.

The women’s health gap is bigger than any one person can explain in 800 words. It goes beyond research and representation and bleeds into social structure. The truth is, healthcare has a long way to go before women will be able to access medical care that seeks to treat them holistically and fairly.