1,095. Does this number have significance to you?

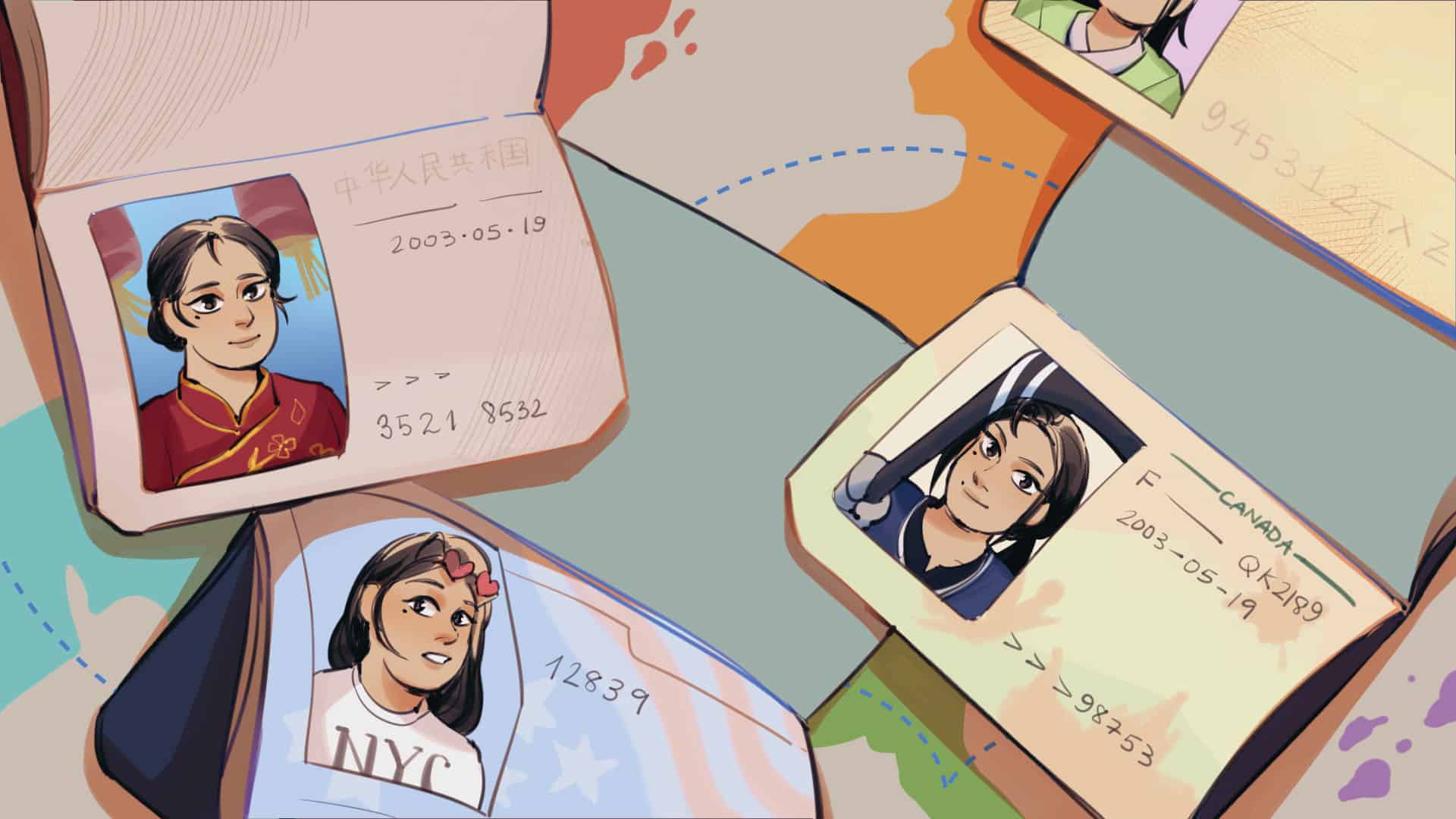

For me, it’s an identifier. But that’s because I am an immigrant.

Over the span of two decades, I’ve lived in five countries that reach across two continents. I wait for the day when there is a match between the country of my passport and my country of residence. I wait to be untied from the place that I emigrated from at eight years old. I wait to be the citizen of a land that I can proudly call my own.”

My family filled out the application package for Canadian residency in 2018. Our relatives from Alberta sponsored us. Two years later, our application was accepted — upon notification, we instantly packed our belongings and left Bahrain, where we were living at the time. We started counting to 1,095; the number of days we’d needed to have physically been in Canada before applying for citizenship.

As we count upward, I look forward to gaining the privileges that come with a Canadian passport, like applying for a work visa in a neighbouring country or travelling on vacation without having to file for a temporary visa. I slowly replace the parts of my cultural identity — an accumulation of work and lived experience in India, Singapore, Dubai, and Bahrain — that pose an obstacle in the way of my seamless integration into Canadian life.

Until I can define myself with the specific label of Canadian citizenship, I switch between identities. I’m an Indian expat and a resident of Canada. I’m categorized as a first-generation South Asian immigrant on my Permanent Resident Card, but I am a ‘white-washed non-resident Indian’ on drunken nights spent at fraternities. I’m a ‘try hard’ in the opinion of family friends because I enjoy placing gifts under the Christmas tree, and I don’t abstain from eating beef because I spent time in a place where it was a common delicacy.

The unfair ostracization that I’ve been the bearer of is not my experience alone. In their 2014 study, Brunel University’s Nelli Ferenczi and Tara C. Marshall found that immigrants who are anxiously attached to cultural identities differing from their place of residence experience increased marginalization from family and friends. This ostracization can be even more damaging to students because it occurs during a time in which they attempt to solidify their identity in terms of relationships, social achievements, and career advancement.

Considering that in recent years, Canada’s foreign-born population has grown four times faster than the Canadian-born population, Canada has truly begun to embody a mixed culture. As our nation’s cultural identity becomes increasingly fluid, students are pressured to maintain their ethnic integrity while adapting to the multicultural environment within which they reside. This constant balancing act can lead to students experiencing cultural alienation as they struggle to align pre-existing values with Toronto’s intercultural environment.

Alienated, but not alone

For Lily Fan, a third-year student at U of T, alienation has grown into a familiar feeling. Fan was born in Vancouver, but moved to Shanghai, then America, and later Hong Kong during her childhood. Because of her constant relocation, Fan had to constantly adapt to fit in with drastically different norms than the ones she’d become acquainted with in the country from which she emigrated.

“In Hong Kong, when you talk to people working [and] staff… I feel like they’re less friendly,” Fan remembered. “They’re less willing to have a conversation with you. If you take a taxi, the taxi driver is going to completely ignore you.”

It wasn’t only the small details that Fan had to familiarize herself with. In 1997, Britain — which had previously ruled Hong Kong — handed Hong Kong back to China. In the process, the two countries signed a treaty specifying that Hong Kong would preserve its existing freedoms for residents, as well as maintain an autonomous legal system, until 2047. Recently, advocacy groups have accused China of meddling with these rights. So, while living in Shanghai, Fan — who doesn’t “politically agree with China” — observed stark political norms that didn’t align with hers.

However, this conflict isn’t the only factor that shapes how Fan self identifies. Fan admitted that she is “more familiar with the things that go on in the Western side of the world, rather than what happens in China,” but prefers to describe her identity as neither Canadian nor Chinese because of her lack of participation in both countries’ celebrations.

“I’m basically in between,” Fan explained. “I know of things [about China and Canada], but I don’t actively participate.”

Being “in between” cultures is a feeling that other students can relate to. In diverse communities such as U of T’s, cultural assimilation — the process in which minority groups adopt the values and beliefs of society’s dominant culture — no longer reflects the norm. Instead, as Canada welcomes its highest number of immigrants since 1946 — 113,699 within 2022’s first quarter — the intermingling of cultural practices between immigrant groups now seems to shape and redefine Canada’s population.

This transformation of cultural identity is most evident day to day. By 2036, 30 per cent of Canada’s population is projected to be made of immigrants. Toronto suburbs are adapting to this shift by forming ethnic community hubs, which contain those communities’ shopping centres and places of worship, as well as professionals who speak their language.

However, this diversity in services hasn’t always been the case.

For Sarah Igcasenza, a second-generation immigrant from the Philippines, moving to Canada meant sacrificing speaking Tagalog, which others told her she spoke “fluently” when she was younger. Ultimately, this lack of practice led to Igcasenza forgetting the language altogether, which made visiting the Philippines stressful later on.

Igcasenza recalled a conversion she’d had with a Tim Hortons cashier while abroad. When she mentioned she didn’t speak Tagalog, the tone of the conversation immediately shifted to being “dry,” which made Igcasenza feel the need to apologize.

“I feel like [not knowing a language] almost drives you further away from being more tied to your culture,” Igcasenza reflected. “[People at home] make you feel like you should be ashamed that you don’t know much.” Eventually, this shame deterred Igcasenza from engaging with Tagalog altogether; “[I thought]: ‘I’m just going to stay away from it.’”

In the process of assimilation, many immigrants let go of what were once important cultural elements of their identity, such as their native language, to feel welcome in their new countries. Though this initial loss of identity usually allows immigrants to fit in, it eventually leads to the complete loss of connectedness with one’s ethnicity.

“I feel like if I grew up around more Filipino people or if I knew more Filipino people in school, I would be probably more engaged in it,” Igcasenza shrugged. “I feel very Westernized now.”

Members of cultural minorities require support from their communities in order to maintain their roots. So why do we define cultural identity with such concrete bounds when doing so only fuels further division?

Support networks

The experience of immigrants who were raised in Canada differs greatly from that of new immigrants. Moving to a large, diverse country — such as Canada — as an adult means that individuals can maintain a connection to their ethnic roots and practices.

In this case, cultural assimilation is no longer an act of stripping away cultural values; instead, it’s an attempt to add to another country’s larger culture. This aspect of the immigrant experience has become common in largely diverse spaces such as Canadian universities.

For Shreyansi Gandhi, an international student from India, moving to Canada initially proved to be a significant struggle. Gandhi remembered that, because she moved in September, she missed out on “Indian festival season,” a period which she described as running from September till November. During this time, popular celebrations and festivals such as Ganesh Chaturthi, Navratri, Durga Puja, and Diwali occur.

“My friends and family back home were able to celebrate,” Gandhi recalled. “Landing into a place for the first time, you’re already feeling like you’re missing out and then… missing out on something so special kind of doubles down on that feeling.”

Eventually, Gandhi found a community of Indian students with whom she could celebrate these festivals. In the future, she and her like-minded group of friends — she describes the bunch as being “not super traditional” — hope to create spaces that allow them to access their cultural roots.

“How we come together… is so much more diverse now because everyone brings their own traditions from back home,” Gandhi explained. “I’m exposed to different ways of portraying what being Indian and being Hindu means to people.”

Retaining cultural practices provides a needed source of support for immigrants, as a lack thereof has been found to exhibit poor mental health. On the other hand, protective factors, such as family and ethnic community support, have been associated with better mental health. Social support also empowers individuals to cope with and overcome any challenges that may occur during their transition into a new country.

At U of T, several avenues of social support exist for immigrants. These initiatives include student associations for specific ethnicities, such as Albanian Students at U of T; student associations that celebrate certain religions, such as the Buddhist Student Association; and clubs that spread information about the rights and challenges that the new immigrants of Canada face, such as RefugeAid U of T. Similarly, U of T’s Centre for International Experience offers resources about applying for and maintaining temporary status in Canada.

The students I spoke to agree that these supports are needed. “Most Canadians [that I know]… their parents or their grandparents, et cetera, were immigrants,” said Lama Ahmed, a third-year student at UTM. Ahmed lived in Saudi Arabia for 13 years and Egypt for four before moving to Canada. “So I think [that] is something really unique.”

Ahmed acknowledged that, because her brother had been living in Canada prior to her move, her transition into the country was “easier than most other [immigrants’ experiences].” She explained that her brother was married, so she could rely on him, his partner, and his partner’s family in times of struggle. After her move, Ahmed met other people from Egypt, who helped her stay connected to her culture.

“Anytime I am feeling homesick… I can go hang out with my Egyptian friends and we can watch some Arabic TV shows or listen to some Arabic music,” Ahmed shared. “There’s always some sort of outlet that I can [use to] connect.”

An irreplaceable journey

Ahmed’s experiences are common; 75 per cent of Canada’s population growth comes from immigrants. This status quo is only expected to intensify — in 2022 alone, Canada is expected to welcome between 360,000 and 445,000 new permanent residents. These people’s unique stories will undoubtedly change the norms of cultural identity and expression. In the 2016 National Household Survey, more than 250 ethnic origins were reported, 13 of which surpassed the one million population mark.

The different perspectives that exist among U of T students capture the diversity of the Canadian immigration experience. Despite the distinct characteristics of each interviewee’s story, it’s clear that there is a common sense of unity between those who have dealt with the stressors of immigrating to a new country. Each story embodies a different aspect of a shared journey that ultimately a large proportion of the Canadian population can relate to.

Previously, clearly explaining my mixed identity seemed like an obstacle that I couldn’t overcome. At some point, I’d still be very happy to confidently say, “Hey, I’m Canadian, and I’d love to show you around where I live,” — but now, I can wait for that day to come instead of counting up to it.

Being accepting of different values and creating traditions that link Canadian culture to life abroad are some benefits to being an immigrant that interviewees mentioned. The conversations I had with them transformed the way I view myself; I no longer feel compelled to use a label that doesn’t stick, because that label could never fully encapsulate all the lived experiences that I bring to Canada.

It’s like Ahmed said: “[When you’re an immigrant], you’re never fully one or the other, but that’s a really unique thing — to feel blended.”