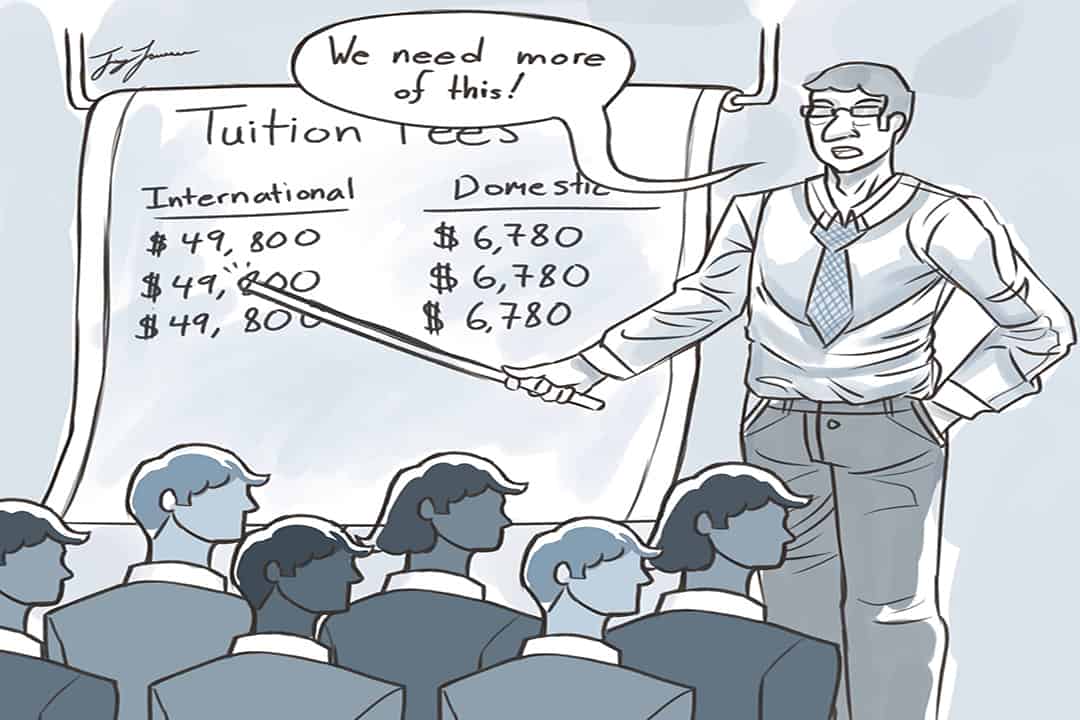

In March, over the objections of its three student governors, the University of Toronto Governing Council passed a differentiated tuition schedule. Beginning this academic year, international students will see a two per cent tuition increase, domestic students from outside Ontario will see a three per cent increase, and Ontario students will see no increase at all.

These increases are a direct result of decades of austerity at the provincial level. Cuts to provincial funding for postsecondary education force universities to either cut revenues or raise tuition — it seems that means raising tuition for out-of-province and international students. Either option, cutting revenue or raising tuition, damages the U of T community at large. For students, the only way forward that I see is to change the way funding is allocated at the provincial level.

Money has to come from somewhere, and it’s not coming from the province. In 2019, Ontario reduced provincial tuition by ten per cent. When asked about how postsecondary institutions would recover their lost funding, Merrilee Fullerton, the then-minister of training, colleges, and universities, replied, “[I] fully anticipate they are capable and able to make adjustments.” In the subsequent year, the province froze tuition until 2022. However, the province has only maintained that freeze for domestic students.

This is only the recent history of education austerity in Ontario. Since the drastic cuts in the 90s, the policy on higher education has, with exceptions, allowed for either tuition freezes or caps. Between 1992 and 2005, the amount of funding the province was dedicating to postsecondary education fell by about 15 per cent. During the same period, the number of students enrolled in postsecondary education rose by 38 per cent.

In this climate of austerity, there is no good funding scheme. Students on the governing council were right to raise issues with the tuition increases planned for this school year. This increase will disproportionately affect students from other provinces that cannot afford the increase in tuition.

However, there seems to be no easy solution for U of T as there are few options for the university to make up for the funding cuts. If the university increases tuition, that will disproportionately affect out-of-province and international students. However, if its revenue decreases, that may mean less money for financial aid, teaching, and student resources. The U of T community cannot afford to lose important aspects of student life such as queer initiatives, student communities, or mental health services.

The decrease in funding will also negatively impact more than just students. It may be easy to forget that universities require massive amounts of labour to run.

From cleaning the classrooms to cooking dining hall food and everything in between, a great deal of the work done at our university is done by U of T’s staff. Many of these workers are unionized; their unions help rectify the power imbalance between workers and their employers. Here at U of T, unions may secure real benefits for workers, but those come at a cost to the university. However, by outsourcing different services, the university can decrease costs to keep up with the cuts to funding.

The way I see it, U of T is a community, to which there is no greater threat than austerity. As Fred Moten and Stefano Harney write in their monograph on education politics, The Undercommons, “It cannot be denied that the university is a place of refuge, and it cannot be accepted that the university is a place of enlightenment.” Without lionizing the university, it is necessary to recognize the refuge and community that U of T provides to many students. We must defend that.

To stop tuition increases, we have to escape the cycle of austerity that drives them. When the university is underfunded, it is forced to make the difficult decision of either increasing tuition or reducing revenue so that it can continue supporting itself.

To escape this cycle, we need to change the way funding is allocated at the provincial level. This means replacing the Progressive Conservative government in the next election with a government that prioritizes postsecondary education. However, voting is not enough. We need to organize student demands into a coherent movement capable of advocating for changes to provincial funding of postsecondary education. The seeds of this struggle are already sown. Soon it will be the time to reap.

Zed Hoffman-Weldon is a third-year student at University College studying physics and public policy.