Two years ago, I attended my first ever lecture at university. Everything about university was foreign and nerve-wracking to me. My school uniform era had finally come to an end. I was out of the small secondary school classroom — not in a grand lecture hall, but back in my room, connecting to my new classmates over Zoom.

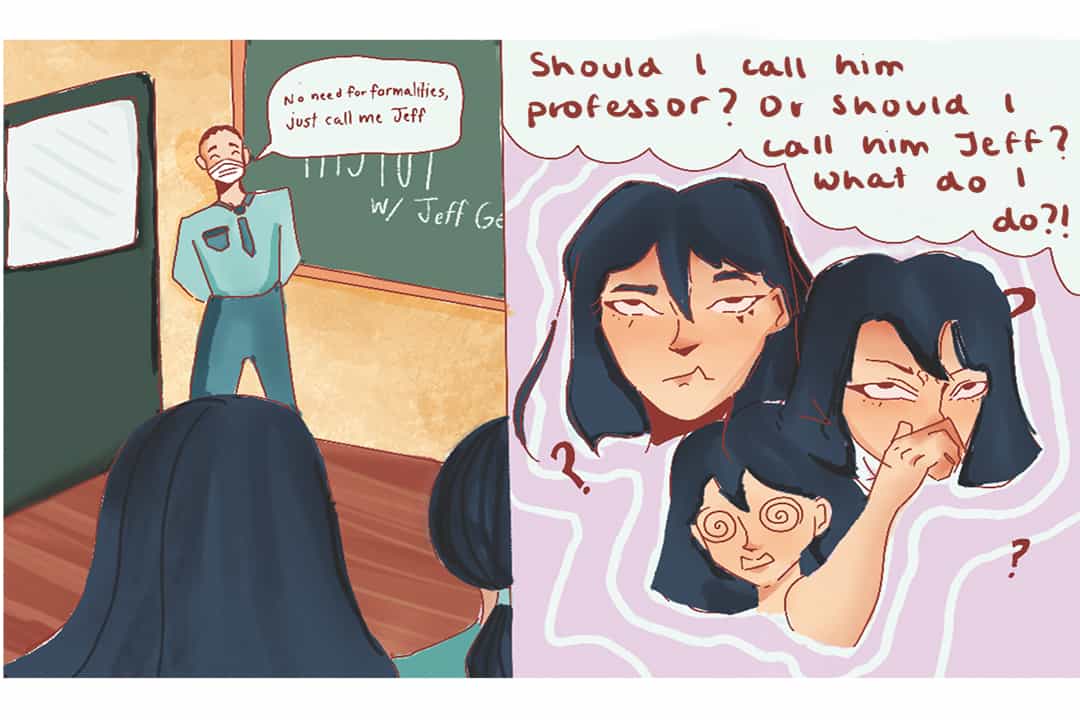

It was my first time meeting my professor. He introduced himself to the class: “Hello everyone! My name’s Jeff. Please don’t call me Professor, call me Jeff.”

That was new. In fact, it was so foreign to me that it took me almost half of the semester to finally be able to comfortably call him Jeff. I questioned the reasons for my discomfort. Was I too prudish?

Being born and raised in Hong Kong, I have been bilingual my entire life. Cantonese Chinese is my mother tongue and the language I speak most of the time back home. I have also been learning English for as long as I can remember. Interestingly, Cantonese spoken by Hongkongers usually follows the grammatical structure of Cantonese Chinese with English words and phrases mixed in — a pretty representative example of how unique and hybridized Hong Kong culture is. In a nutshell, Hong Kong culture has a base of traditional Cantonese culture mixed with British and Western cultures.

As in traditional Cantonese culture, respect for seniority is prominent in Hong Kong. When we address people in Cantonese, it is important to address people with honorifics to show respect to elders. My parents taught me to never address elders by their first names because it is impolite and offensive.

In secondary school, not only was I told to address the staff by their title and last name, but I also learned that there were consequences for breaking this rule. Back in third grade, a fellow classmate of mine called a teacher by her name in a playful manner and was scolded by her in front of the whole class. As a result, I felt a sense of wrongness in addressing Jeff by his name that was deeply rooted in me. It felt impolite and wrong for me to address Jeff without his title. I was not too prudish — I was just not used to it.

Clearly, this mindset is not limited to when I am speaking Cantonese. When I address an elder in English, in addition to their preferred name, I try to find the best honorific according to their age and seniority. It doesn’t hurt to be a little more formal and polite, right?

However, from my experience in the English-speaking world, I find that people prefer that others drop all honorifics and call them simply by their preferred names. My American-born, English-speaking cousins call their siblings and cousins simply by their names. When I visited them last summer for the first time in seven years, one of my cousins whispered to my aunt,

“How do I call her?”

“Sum Yue (biu2 ze2). You’ve always called her this.”

“That’s so long. It’s weird.”

‘Biu2 ze2’ — i.e. 表姐 — is an honorific for an older female cousin on the maternal side. It might sound distant and awkward for my cousin, who is seven years younger than me, to call me by my name with an honorific. It might seem too formal and give off a sense of hierarchy to non-native Cantonese speakers. For me, I like being called ‘biu2 ze2’ a lot — not because it fluffs my ego or marks me as a superior, but because it makes me feel closer to my cousins. It is the honorific that emphasizes our relationship as cousins, highlighting the sense of family, especially with relatives I have not seen in years.

Conversely, as the youngest cousin on my mom’s side, most of my cousins are older than me by at least fifteen years and I only see them during festive family gatherings. Calling them ‘biu2 ze2’ or ‘biu2 go1’ — i.e. 表哥, an elder male cousin on the maternal side — reminds me that they are family rather than some strangers with whom I am having dinner. I find that honorifics are especially helpful in making me feel more in touch with distant relatives from my extended family.

English speakers usually only use the words ‘aunt’ or ‘uncle’ for their relatives. However, I address all middle-aged people by ‘auntie’ — 姨姨 (ji1 ji1) in Cantonese — or ‘uncle’ — 叔叔 (suk1 suk1) in Cantonese. Not only does it draw me closer to strangers, but it also shows respect for elders. Because, for Cantonese speakers, the terms ‘auntie’ and ‘uncle’ are not limited to relatives, I like to joke with my non-Cantonese speaking friends that everyone in Hong Kong is my auntie or uncle.

Apart from honorifics, when it comes to preferred names for friends, I noticed that Cantonese speakers of our generation prefer to use their full names, while English speakers prefer their first names or nicknames. My Cantonese-speaking friends and I call each other by our full Chinese names. Even if I called a Cantonese-speaking friend by their English name, it would be by both their first and last name. Their full names in English usually have three syllables, echoing the three-syllabic characteristic of most Chinese names. Using their full names may sound formal and a little aggressive — sometimes it is — but it shows how comfortable we are with each other.

On the other hand, when I introduce myself to strangers, I usually go by my English name. It sounds more casual in an English-speaking environment, but personally, it feels more formal in a Cantonese-speaking environment. I have not heard any of my close friends back home call me Emily in so long that I don’t even recall the last time any of them did that. It would feel so foreign to hear my English name come out of their mouths. There is a sense of distance when Cantonese speakers call me by my English name — maybe it is the language, or maybe I am just used to people calling me by my Chinese name.

I am, of course, comfortable with both Cantonese and English ways of addressing people. I flip the switch depending on where I am and to whom I am talking. Still, I like to embrace my hybridized mindset of addressing people. It is a way for me to keep in touch with the hybridized culture I grew up in and my mother tongue — Cantonese — while being away from my home.