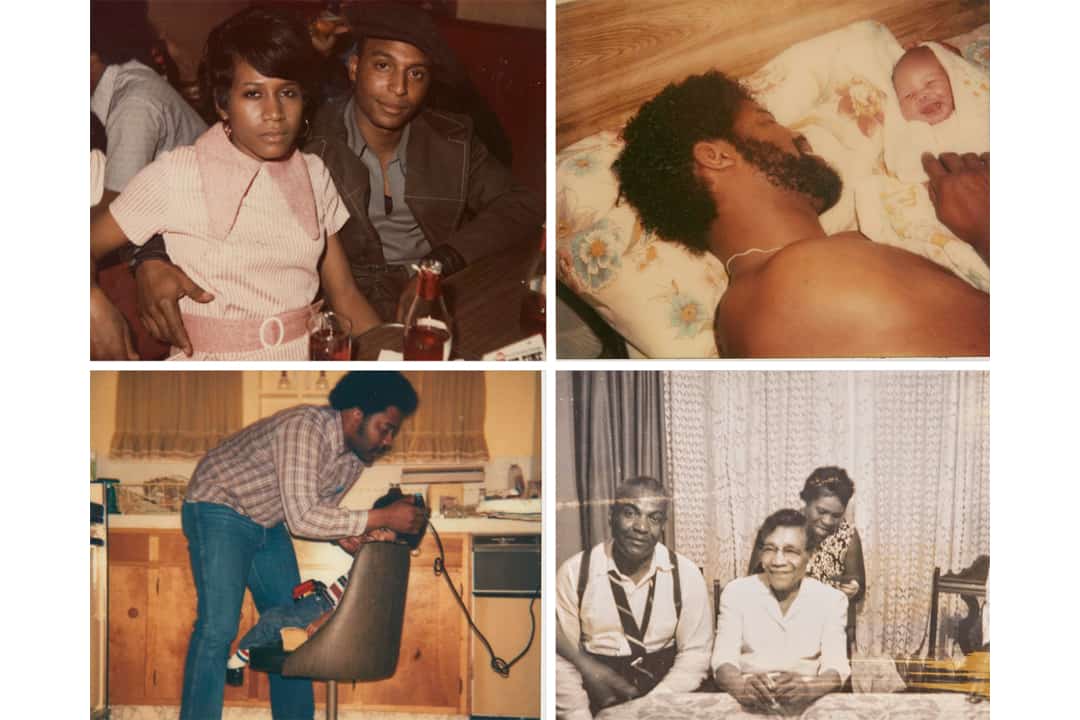

What Matters Most: Photographs of Black Life is a current exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario, and is running until January 8, 2023. Zun Lee is the co-curator and collector of over 4,000 family photographs spanning from the 1960s to the early 2000s, showing intimate scenes of African-American domestic life.

The exhibition is concerned with instant-print photography as a mode of Black self-representation, as well as with the politics of dispossession and white supremacy, which led these lost family heirlooms to be displayed in a museum in the first place.

When you enter the exhibit space, which spans two rooms on the AGO’s first floor, you are surrounded by black magnet boards mounted on the walls of the room, upon which the polaroids of quotidian life rest. The photographs span time and place, and are very loosely organized — birthdays, weddings, dinners, and moments of rest are spread out next to each other, pointing to the loss of context and of meaning that surrounds the entire Fade Resistance collection.

Lee has been collecting these “orphaned ghosts” for years and writes that these polaroids “highlight the importance of ‘seeing ourselves as we are,’ ” and that they “remind us that there is a vivid history of Black visual self-representation that offers an eerily contemporary counter-narrative to mainstream distortion and erasure.” This affirmation of Black life, of Black creativity and self-representation, is a subversion of the conventional photographic representation of Black bodies.

The curators of What Matters Most take care to represent Black life as diverse, and treat the subjects of the photographs with care and attention, almost as if they had been behind the camera themselves. Yet, the enormous scope of the loss and dispossession that surrounds these photographs is felt strongly when you’re walking around the exhibit. The absence of writing around these portraits of family, friends, and lovers stands in stark contrast to the expressions of love and autonomy within the polaroids themselves.

In the absence of writing and with attention to the fact that these family archives have been ripped from families, the exhibition invites visitors to take part in writing themselves. In the middle of the room, there stands a table, with copies of the polaroids strewn across it. Next to it, pens and books: prompts for the public to take part in the collective task of reckoning with this dispossession, of reckoning with what matters, of reckoning with this exhibition’s very place in the colonial institution that is the museum.

The position of these photographs in this space, as artwork in a museum, elicits a wave of overlapping and contradictory emotions. I felt, as a transient visitor to the artifacts of these people’s lives, like somewhat of an interloper. These folks may not have wanted to have these artifacts displayed in a museum and to have scores of viewers each day project their lives and experiences onto the muse’s, into the silences surrounding the white frames.

As a white settler, what drew my attention were the ways in which the white gaze and white ways of looking and taking photographs, especially in the museum, have been weaponized in order to culturally and materially systematically dispossess Black and Indigenous people. The visibility of these ongoing histories is heightened in What Matters Most.

I think that the curators are aware that their exhibition might elicit these feelings in visitors: they do not pretend that these images are being presented neutrally. Rather, they are aware that the very act of gazing at these portraits the way one might gaze at a painting speaks to the societal mechanisms of dispossession that gave rise to this exhibition, as well as pointing to the profound beauty and importance of these lives. On each magnetic panel holding the photographs, there is a note for visitors to get in touch with the museum in case they recognize anyone in the photographs. The potential for reconnection further cements this exhibition’s subversive status.

I had never seen an exhibition like this at the AGO — one that is made up in large part by the poetic potential of people who visit it, who come together and think together about photography and history.

“The fact that these images are now separated from the erstwhile owners makes one speculate about their potential fate,” Lee wrote. “We don’t know what happened to the individuals but the power of their stories lives on. I’m publishing this collection from my archives to help preserve these stories. We may never fully grasp what these Polaroids originally meant. We can, however, feel inspired to reimagine what it means to see ourselves as we are.”

The exhibition questions its very status, and invites the public to come together to collectively grapple with these pictures, notions of communion, and belonging, and the question: what matters most?