According to Statistics Canada, Black populations of African, Caribbean, and Canadian descent, on average, earn between $2,900 to $8,000 less than their non-racialized peers. Black people are also more commonly unemployed, more likely to encounter disputes with the law, and more likely than their non-racialized peers to experience discrimination.

However, the likelihood of racial discrimination varies depending on educational achievement. According to a Pew Research Center survey, college-educated Black Americans report fewer experiences of racial discrimination. Racial disparities exist at every level, but the pursuit and opportunity of education and literacy come as a saving grace against a deeply flawed system.

Therefore, on the first day of Black History Month, it felt right to celebrate Black literacy.

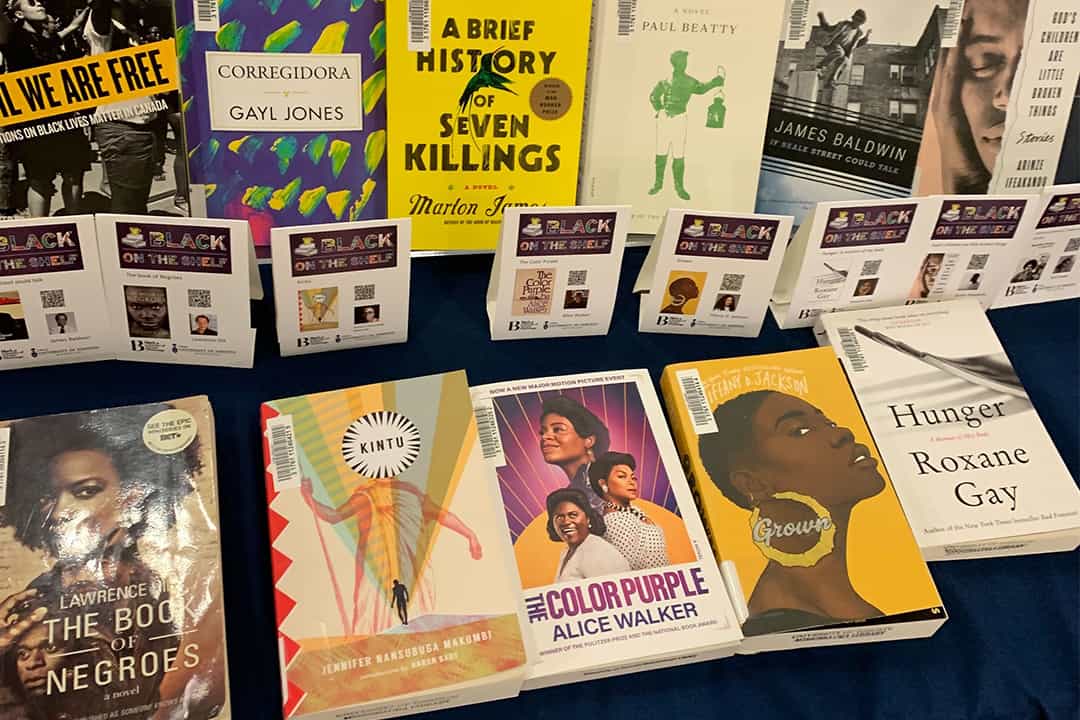

At 1:00 pm on February 1, Black at UTM — an initiative born from U of T’s Anti Racism Task Force recommendations — partnered with the UTM library to honour and celebrate Black literary excellence. I attended the event, called “Black on the Shelf,” which launched a collection of 31 books written by various Black authors into the university library’s catalogue. The books had been carefully chosen by Black students and faculty, and were displayed at one end of the space, overlooking a number of faculty, students, and staff mingling, conversing with each other as they interacted with the texts.

The event reinforced the power of harnessing education and language as tools for telling our own stories, making space for ourselves, and defending ourselves against those who wish to harm us.

I have long believed that in pursuing freedom and challenging oppression, we must start with promoting literacy, and redefining good literature for ourselves. For Black people and other racialized groups, we must dismantle the sacred colonial texts within classrooms and replace them with a body of works through which we are all seen and through which we can all engage equally.

Universities are cultural pillars that inform society’s norms around race, democracy, and welfare. Out of them, tomorrow’s leaders, civil servants, and stakeholders are licensed to inherit the world, and they must be certified to have the right materials, methods, and concepts to govern society.

Given that literacy and literature are two factors of the greatest importance in the struggle for the emancipation of Black people across the globe, centring them in discussions and celebrations around Black History Month marks progress.

As Frederick Douglass said, “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” In his memoir The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Douglass testifies that by learning to read, he gained the power of truth over the conscience of his slaveholders, a view of the pit of his condition, through which he could build a ladder and finally escape.

In one of the books launched — Toni Morrison’s The Source of Self-Regard — Morrison questions why American literature, by definition and convention, is set aside from African or Asian-American literature. She boldly challenges the white men origins of academic measures of literary and humanistic value, as well as aesthetic criteria; the fact that historically, contemporary literary discourse and production has been “the protected preserve of the thoughts and works and analytical strategies of white men.” She highlights how when we think of great American or British literature, we think of names such as Ernest Hemingway, T. S. Eliot, F. Scott Fitzgerald, William Faulkner, and Mark Twain.

What “Black on the Shelf” did reflects Morrison’s argument against the conventional literary canon. The event felt like the creation of a literary canon for Black people, by Black people, composed of Black people. This is important for the ways in which these books may guide other Black people to perceive themselves and the world, and the ways in which the wider world is opened up to the vast range of stories and complexities in the lives of Black folks.

In UTM’s case, this Black literary canon comprises books like Gayl Jones’ novel Corregidora, a strange, unsung classic that explores the deep-rooted effects of generational trauma and gender-based violence through the fraught sex life of one Black woman. There’s also Marlon James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings, which novelizes Jamaica’s bloody political life in the ’70s and the CIA’s plot to assassinate Bob Marley. There is Mikki Kendall’s Hood Feminism, as well as Dennis R. Edwards’ Might From the Margins which explores how the Christian faith has historically fueled the mission for liberation in spite of the pro-slavery theology of early American Christian identity.

These are books that present new ways of thinking and modes of being — an ethos that is reflected in the growing phenomenon of Black studies programs at Canadian universities like York, Queen’s, and Toronto Metropolitan University. This trend of Black studies programs must be partnered with lasting infrastructure for the support, care, and promotion of Black students, staff, and faculty alike.

Keep adding Black authors to libraries, Black studies programs to curriculums, and accepting Black experiences as worthy scholarly inquiries. This way, we give ourselves the means for protection and nurturing by engaging with Black literature as world literature, and the discourse around it as worthwhile education. In compiling a canon to which we may reference and upon which we may reflect, we may give ourselves the power of truth over the conscience of the institutions that we serve, and forge paths to freedom for ourselves and others like us.

Divine Angubua is a third-year student at UTM studying history, political science, and creative writing. He is the editor-in-chief of With Caffeine and Careful Thought and a staff writer at The Medium. He is an associate comment editor at The Varsity.

No comments to display.