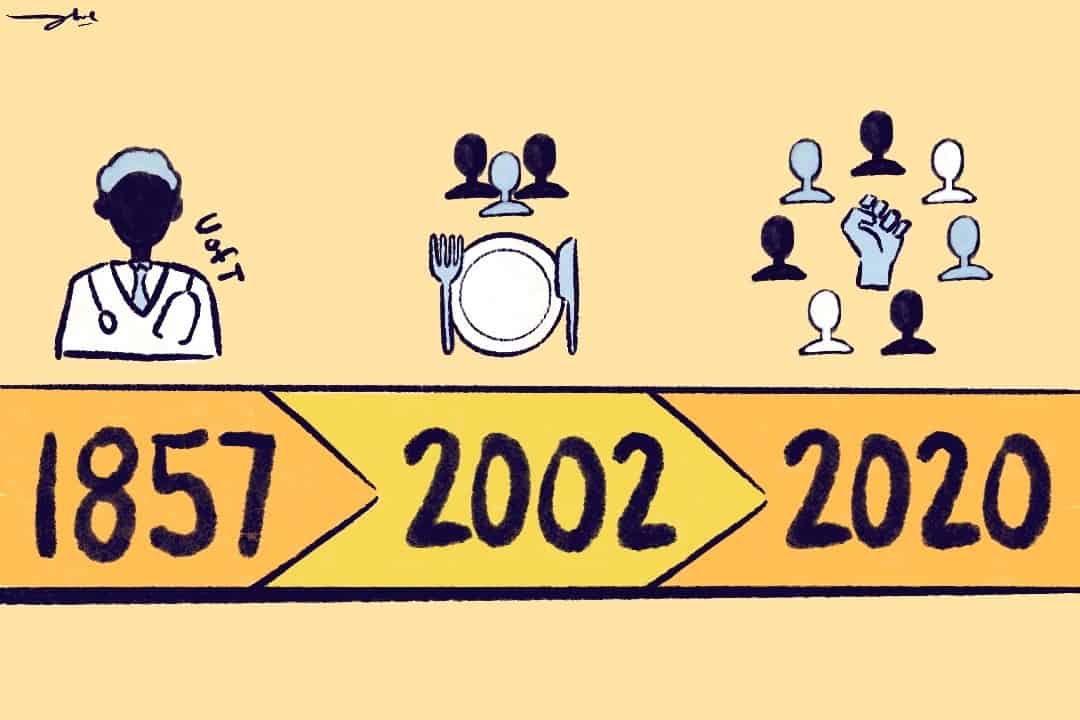

The first Canadian-born Black doctor. A speech that charted the way toward school desegregation. A luncheon celebrating Black history. This Black History Month, The Varsity is here to highlight significant events in the university’s history specifically about U of T’s Black community.

The first Canadian-born Black doctor

Founded in 1827, U of T’s doors were originally open to Black students. One notable early alumnus was Anderson Abbott, the first Canadian-born Black doctor. In 1857, Dr. Abbott enrolled at University College — established at U of T in 1853 — to study chemistry. In 1858, he began his medical degree at the Toronto School of Medicine, which later became associated with U of T. After completing a supervised placement with Dr. Alexander Augusta — a family friend and Black community leader who lived in Toronto at the time and received his medical degree in 1860 — Dr. Abbott received his medical license in 1861.

Dr. Abbott ran successful medical practices — first in Dundas, Ontario, and later in Toronto — and wrote for multiple publications on topics such as biology, desegregation, and politics. Each year, U of T now awards one Black undergraduate student the Dr. Anderson Abbott Award, which is worth $4,000 “on the basis of academic achievement, financial need and contribution to the black community.”

Setbacks

A few years later, U of T backtracked by implementing several segregationist laws that barred Black students from attending the school. Segregation was particularly prevalent in education, with Ontario and Nova Scotia setting up legally segregated schools in the late 1800s to keep Black students separate from other students. U of T also refused Black students admission under segregation policies — in one documented case, U of T initially accepted Lean Elizabeth Griffin, who applied to U of T medical school in 1923, but later denied her entry when the administration realized she was Black.

Leonard Braithwaite — a U of T alumnus and the first Black Canadian elected to a provincial legislature — played a significant role in challenging school segregation. In his first speech to the Ontario Legislature on February 4, 1964, Braithwaite spoke out against the Separate Schools Act — a law that permitted racial segregation in Ontario K–12 schools — in a speech at Queen’s Park. He argued that the days of segregated schools had passed.

Braithwaite put forward a motion that the province remove the clause allowing segregated schools. One month later, education minister and future Ontario Premier Bill Davis introduced a bill that repealed the 114-year-old provision allowing for segregation. The last segregated school in Ontario closed within a year, in 1965.

Contemporary history

One of U of T’s specific actions to tackle injustice is the creation of the Anti-Black Racism Task Force (ABRTF). The U of T administration announced the task force on September 23, 2020, as part of the university’s response to global protests against anti-Black racism.

In March 2021, the ABRTF delivered a final report outlining 56 action-oriented measures. These recommendations aim to tackle anti-Black racism and promote Black inclusion and excellence across the university’s three campuses.

Assistant professor in the Department of History and historian of modern Africa Safia Aidid mentioned in an email to The Varsity that she’s seen a cultural shift at U of T in how it approaches academia and community. Aidid spotlighted U of T’s hiring of more scholars who teach Black Canadian, Caribbean, and African American history. Aidid added that she feels “fortunate to be part of the new wave of young black scholars at U of T.”

Aidid also mentioned a shift in student interest toward Black history. “Students are certainly more engaged and interested in Black history. Many of the students I teach are new to African history, but what brings them into my classroom is a deep interest in Africa and a sense that they aren’t getting nuanced perspectives from the media or pop culture,” she wrote.

As a whole, Aidid recognizes the steps taken by the university to promote greater degrees of Black representation and inclusion. “Though we still have a long way to go, it is encouraging to see these institutional commitments,” she wrote.

Reflecting on history with the BHM luncheon

Another action taken by Black U of T community members that has left a mark on the university is the creation of the Black History Month Luncheon. The luncheon is an annual event that Glen Boothe and his colleagues in the university’s department of advancement — which coordinates U of T’s fundraising and outreach efforts — started in 2002. It features speakers and food and celebrates Black culture and excellence, intending to foster a sense of community and inclusiveness.

On the legacy of the luncheon, Boothe expresses a sentiment of contentment and fulfillment in all it has done to positively impact the Black community at U of T. “The biggest satisfaction is the continued and growing support [for the luncheon]. Growth is always a good barometer of success, and each year there is a new group or individuals volunteering to be a part of [the luncheon] in a meaningful way,” wrote Boothe in an email to The Varsity.

No comments to display.