The moment November 1 arrives, Toronto swiftly begins its transformation into a sensory overload of Christmas cheer. Just north of UTSG, luxury shop windows extravagantly advertise Christmas sales and trees are strung with festive lights. Whether you’re Christian or not, the holiday is unavoidable; even a grocery run or a quick stop at the drugstore bombards customers with one message: ’tis the season.

Some would argue that Christmas, the dominant religious and cultural holiday in Canada, can alienate those who don’t celebrate. Its overwhelming presence everywhere, from city streets to silver screens, means Christmas’ long history in Canada is cemented and not going anywhere.

Others would argue, however, that Christmas has faced degradation; its true essence has been sidelined for consumerism, and “happy holidays” has become the socially acceptable greeting of choice instead of “merry Christmas.”

What relationship do both Christians and non-Christians have with these “politics of Christmas”? The Varsity spoke with students of several denominations to reflect on their experiences during the holiday season.

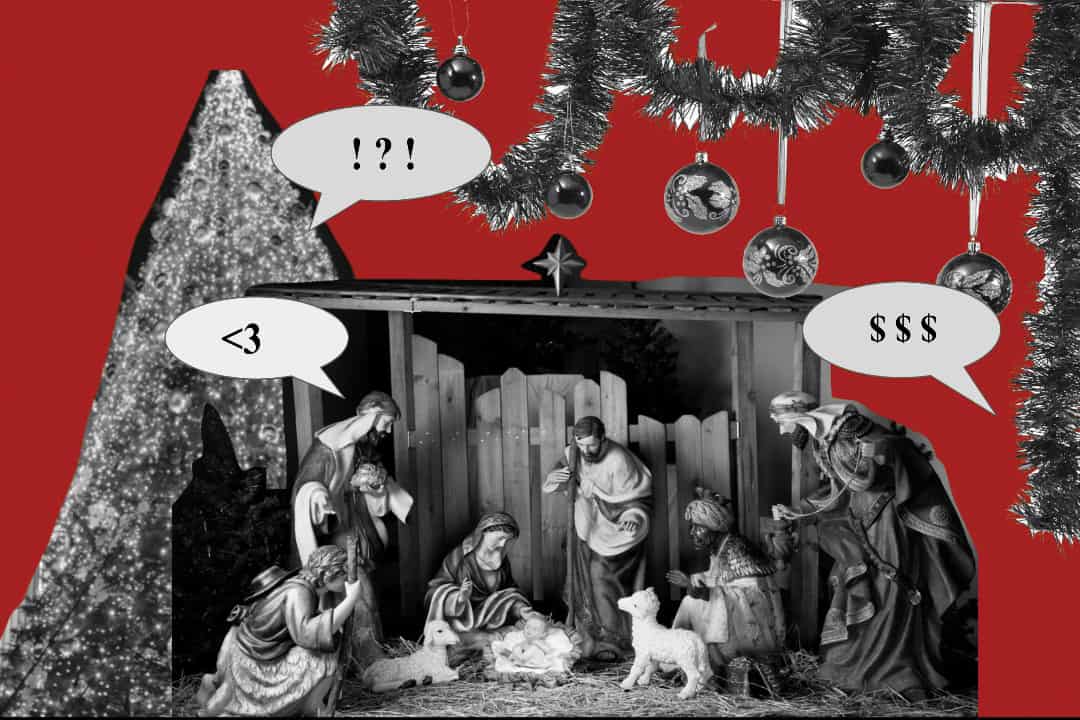

Commercialization

Although the majority of her interactions during Christmastime have been positive, Catholic Toronto Metropolitan University student Aubrey Djauhari says she is a bit torn over the commercial aspect of Christmas.

“With the commercialization of Christmas, you get that surface-level happiness,” Djauhari said “But as a Christian… when we celebrate Christmas, it’s like this deep joy of Jesus Christ [being born]… the Creator of the universe sent his only son for us. And I think that brings a deeper joy which lasts for us the whole year.”

As a marketing student, Djauhari has learned how commercialization works and why it happens. “I don’t think [it’s] some evangelization scheme,” Djauhari explained. “The Pope was [not] like, ‘we must commercialize this.’ ” Rather than displaying nativity scenes, which are much harder to come by, the season is littered with “huge marketing campaigns to sell products and services — sell the idea and the joy of Christmas.”

Manal Kamran, a Muslim student at U of T, also took issue with the commercialization of Christmas, but for a different reason. “[When] you go to Safeway in December, there’s candy cane decorations everywhere, and they have eggnog on display. Safeway is transformed for this holiday, and then [when] one of our Muslim holidays comes, Safeway looks kind of normal.”

Kamran agreed that the commercial emphasis on Christmas rather than the religious prevalence of Christianity caused her alienation during the holiday season. For Kamran, the commercial bonanza of Christmastime exacerbates her alienation, while for Djauhari, it can feel like something sacred to her has been cheapened. As cliché as it is to place all the blame on capitalism, the blend of religion and mass marketing is perhaps a common issue among people of all denominations.

Regardless, both Djauhari and Kamran could still appreciate how commercialization lends itself to developing the Christmas spirit. Although Kamran admits that feeling excluded from Christmas festivities used to bother her, she gained a greater appreciation for the pomp and circumstance of the season after seeing people prevented from celebrating as usual during the pandemic. Djauhari noted that the spirit of giving gifts and the atmosphere created by Christmas marketing brings a sense of joy to everyone around her.

Merry Christmas versus happy holidays

“Happy holidays” denotes a degree of neutrality and inclusivity, encompassing Christmas and other religious holidays celebrated in December. In North America, wishing someone or a crowd “merry Christmas” can feel like a gamble. In groups where people are culturally and religiously heterogeneous, not uncommon in Toronto or at UTSG, “happy holidays” is an all-encompassing, and consequently safe, bet.

When asked about her preferred greeting, although fine with receiving a “merry Christmas,” Kamran stated she preferred “happy holidays” for its secularism, taking into account the other non-Christian faiths in Canada.

On the other hand, happy holidays’ secular nature may reduce the traditional meaning of the season. “I don’t passionately hate ‘happy holidays,’ ” Djauhari said. She appreciated that it’s a popular expression that does not aim to erase Christmas. However, she admitted that her “heart breaks just a little” that a celebration so meaningful to her often gets a secular treatment in conversation.

In Canada, the reason for celebration —– the warm atmosphere, the lights, the holiday break —– during this season was originally Christian. People of all faiths can enjoy the secular benefits of this religious tradition, be it Toronto’s annual Christmas Market or the Nutcracker ballet, which Kamran, for example, attended with her family despite not being Christian. Thus, perhaps the joy a Christian celebration can bring to those of all religious backgrounds should not be overlooked.

The debates surrounding holiday greetings and the commercial dominance of Christmas ultimately come down to the validation a religion receives in the mainstream. Do the department stores enthusiastically acknowledge your faith with decorations and sales? Do your colleagues acknowledge your religious beliefs when wishing you goodwill over the winter break? Recognition is always welcome, but in a society where religious tradition has become so far removed from its secular festivities, deeper spiritual meaning during the holidays is what you make of it.

Kamran put it well: “I’m slowly coming to the realization that the commodification of a holiday has no bearing on how important or special it actually is… you get to decide how special it is to you. Not Safeway.”