“Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

These words rushed through J. Robert Oppenheimer’s mind in 1945 as he watched the culmination of his work in the Trinity nuclear bomb test. They also echoed through cinemas around the world this summer, just like the explosions which inspired them.

Oppenheimer was attempting to quote a moment from the Hindu text, the Bhagavad Gita, which describes a lengthy dialogue from the epic the Mahabharata. In this moment, the Lord Krishna shows his Supreme Form — the Vishvarupa, whom the entire universe is described to reside within — to the hero-prince Arjuna, and says to him in Sanskrit, “कालोऽस्मि लोकक्षयकृ (kālo ’smi loka-kṣhaya-kṛit).” In English, this is better rendered as “Mighty time I am — that which comes forth to annihilate all the worlds.”

While similar in verbiage, there is a profound difference between the scriptural mistranslation popularized by the father of the atomic bomb and its true meaning.

But Oppenheimer is not alone in his mistake. Erroneous mistranslations of important holy texts are not rare. At the surface, subtle changes in wording are not inherently harmful — a camel may be just as awkward to push through the eye of a needle as a thick rope. But incorrect translations or applications of hermeneutics — the study of interpretations of scripture and literature — can become pernicious when they are used to subjugate or oppress within religions. I believe we must be especially cautious about how those with power among religious communities, as well as those who wish to deride faiths, look to play with holy texts to justify division in and among religious communities.

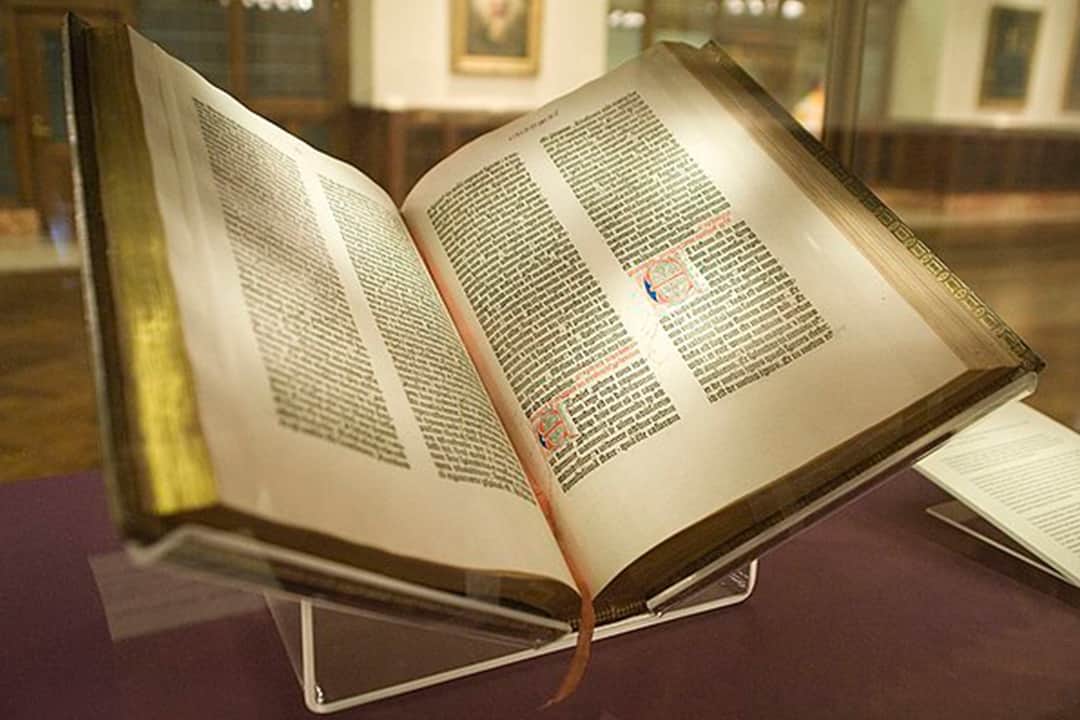

Most of the big world religions have holy scriptures that were written a thousand or more years ago, in languages that have since evolved and changed, and often in languages that practitioners do not themselves speak — such as the more than a billion Hindus who do not speak ancient Sanskrit. Scripture also tends to be written in poetic and often metaphorical language that is not easy to grasp in its original language, let alone via translations. Then there is the issue of interpretation — even if the apparent meaning of a text is clear, its rhetoric may not be.

There are many arguments over the correct interpretation of scripture. Since the great world religions all carry with them a tradition of religious literature — which contains rules, parables, and myths that are meant to guide their followers — they can always contest the translations and interpretations of these truths.

As I have discussed before in my column, religions hold great power over the way in which people and societies conduct themselves. As such, both religious-political leaders within a religion as well as those who aim to be hostile toward religion may become opportunistic when it comes to seizing parts of scripture that can be used to support their own arguments and interpretations.

A classic example of scripture being misused within a community in the past is Christian leaders promoting antisemitism due to their accusations that certain parts of the New Testament discuss Jews persecuting Jesus Christ. This interpretation was one of the Christian theological justifications of centuries of Jewish persecution under western European rule.

Churches no longer teach of this accusation as a way to antagonize Jewish people. The Catholic Church has declared, on at least two occasions in modernity, that there is no basis for antisemitic teachings in Western Christian doctrine. Pope Benedict, for instance, specifically wrote that the references to the “Jews” who accused Jesus Christ in the Gospels of Matthew and John, and in the letters of Paul, are references to the Temple Aristocracy — a group who had political authority in Roman Palestine — instead of a justification for collective persecution.

One often quoted verse of the Qur’an used by those who wish to antagonize Islam as being incompatible with Western society, appears in a Surah, a Qur’anic chapter, which is mostly a narrative about The Last Supper. There is the verse, “O ye who believe! Take not the Jews and the Christians for friends. They are friends one to another. He among you who taketh them for friends is (one) of them. Lo! Allah guideth not wrongdoing folk” (The Table Spread with Food – 5:51).

The word which is translated here as “friends” is the Arabic word “أَوْلِيَآءَ” or “awaliyah.” But the word is not used in reference to personal relationships — rather, it is better translated as “political guardians.”

What God is prescribing to the Arabs is to avoid political alliances with the societies that have been in conflict with them. This is in reference to the tensions between the newly-formed Islamic society of the time of revelation and their neighbours. Muslim Arabs were in constant tensions with the Christian Byzantines and the Jewish tribes in Arabia at the time, which led to multiple confrontations between the groups.

Naturally, over the centuries, as language transforms and entangles, certain phrases and sentiments lose their nuance. Then it is mighty time — the great annihilator of worlds and words — which separates us from the wisdom found in our holy texts. It instead leaves us bickering about details and technicalities which we can use to support our own biases, and fuel our hatred.

While it is true that there are certain parts of all religions which can be criticized in a political, academic, or sociological sense, I believe that this criticism must be conducted while cognizant of the degrees of removal between the reader and the text. When consulting scriptures of our own or those of others, it is important to approach them with respect and with the understanding that there are layers of complexity that have been effaced by the process of conversion from one language to another.

Sulaiman Hashim Khan is a third-year student at St. Michael’s College studying English and ethics, society, and law. He is the Religion columnist for The Varsity’s Comment section.

No comments to display.