On March 15, 2000, 17 student activists stormed the then-U of T president’s office in what would become a 10-day sit-in. The group, Students Against Sweatshops (SAS), was motivated by a singular goal: a set of labour standards for all factories making U of T merchandise.

The school responded by keeping bright lights constantly on, disconnecting power and phone lines, and playing loud music all night — especially the Backstreet Boys and AC/DC. Meanwhile, the protestors relied on food that supporters sent up on a pulley system and sponge-bathed in the president’s sink.

University officials that The Varsity interviewed at the time were adamant that they would not negotiate with the activists. When the protest came to a close ten days later, president Robert Prichard, who had been on vacation throughout, said that the school would “do exactly as [it] had planned, regardless of the illegal occupation.”

However, the SAS’s actions may not have been in vain. Days later, U of T implemented a set of labour standards for manufacturers called the Code of Conduct for Licensees, becoming the first Canadian university to do so. SAS members were also thrilled to hear that it included a living wage — a main demand of their sit-in.

Since it implemented these labour standards 23 years ago, U of T has branded itself as an ethical sourcer of its university merchandise. Trademark Licensing, U of T’s organization that oversees all U of T-branded clothing, writes on its website, “We hope our merchandise is a symbol of the University’s great and lasting impact on our community.”

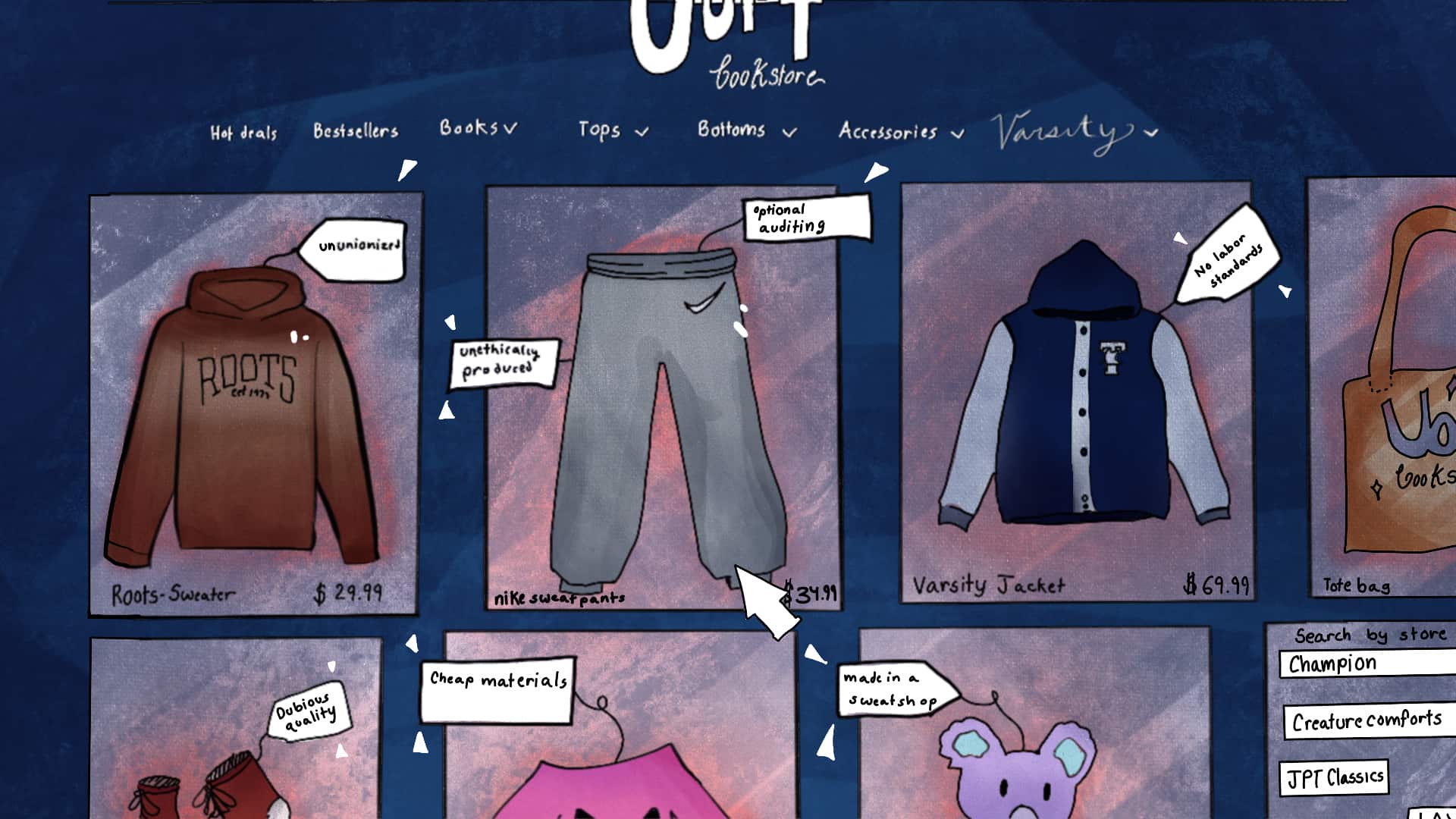

However, The Varsity has uncovered that the labour standards have not been updated for over two decades, one associated auditing organization has only optional factory audits, and U of T merchandise is produced in countries where following the labour code standard of the right to unionize is impossible.

This begs the question: have the seams of U of T’s commitment still held strong?

The current patchwork of policies

Currently, U of T sources its merchandise from supply chains that stretch across the planet. From t-shirts dyed in Haiti to hats sewn together in the Philippines, The Varsity found that, as of September 14, 2022, the U of T Bookstore carries clothing from at least 21 brands, which manufacture products for the school in at least 16 countries.

The school claims that its policies ensure that all of U of T’s merchandise suppliers produce their clothing under ethical working conditions. Trademark Licensing guarantees that merchandise is “produced and created under humane and non-exploitative labour conditions.” These manufacturing standards rely on a network of agencies, commitments, and partnerships, including auditing organizations — which, according to U of T, monitor and enforce this global supply chain.

The basis of this system is the University of Toronto Code of Conduct for Licensees: a set of rules about working conditions that all producers of U of T merchandise are required to follow. These include nine “employment standards,” for instance, the right to unionization, safe working conditions, and a living wage.

The Varsity requested a list of university factory locations from the school, but a spokesperson wrote that “occasional changes in the list of licensed vendors, and shifts in production locations” made such a list unavailable, while a later statement said the data exists but cannot be shared because it “contains proprietary information.”

But even without the list of manufacturing locations, The Varsity still found indications that not all manufacturers follow the university’s labour standards.

Optional factory audits

U of T outsources the on-the-ground work of independent audits, interviews, and investigations into factory working conditions to two American Non-Governmental Organizations: the Workers Rights Consortium (WRC) and the Fair Labor Association (FLA).

In an email to The Varsity, a U of T spokesperson wrote that “both the WRC and the FLA continually investigate factories and worker conditions in response to individual and third-party complaints.”

However, Shelly Han, FLA’s chief of staff, said in an interview with The Varsity that factory inspections only occur if a company decides to participate in audits.

According to the FLA’s website, out of the 23 clothing brands in The Varsity’s September 14 count, only five — adidas, Gildan, Nike, Roots, and Under Armour — are FLA “participating companies,” which, according to Han, means they opted to undergo FLA factory audits.

Meanwhile, the WRC investigates manufacturing locations, based on a list of brands provided by the postsecondary institutions it partners with. Jessica Champagne, their deputy director for strategy & field operations, told The Varsity that the WRC’s database should include all the “broad categories” of items that can be produced with the university logo.

A later U of T spokesperson statement informed The Varsity that “The Fair Labor Association (FLA) does not audit all companies that manufacture U of T merchandise.” The Varsity did not confirm whether the WRC audits the rest of the companies and their supply chains.

Additionally, the spokesperson told The Varsity: “The University takes any issues or concerns flagged by the WRC/FLA very seriously and responds in accordance with the WRC/FLA’s recommendations when these situations arise.”

In a 2016 article, Anne Macdonald, director of ancillary services at U of T, told The Varsity that if the university was alerted of a potential issue, the university would communicate with the licensee to find a solution. Macdonald added that the university would not “just cease doing business with them — our goal would be to try and influence how they operate.”

Looms and labour standards

A U of T spokesperson told The Varsity that U of T reviews its Code of Conduct for Licensees annually “to ensure it continues to reflect industry standards.” However, a textual comparison between the current version and the June 2002 version reveals no changes besides the addition of a short preamble and formatting alterations.

Han pointed out that it may not be a problem that U of T’s Code of Conduct for Licensees has not been updated in two decades, as long as its core is strong enough. She said, “[There are] almost no new labour issues that might come up that probably hadn’t been envisioned for the last 100 years.”

However, twenty first century concerns that pose risks to workers’ welfare — like newly developed surveillance technology, including cameras and time monitors, and COVID-19 transmission risks — may not be covered by a set of guidelines that are over two decades old.

U of T’s Code of Conduct for Licensees also only pertains to labour conditions at the manufacturing stage — like “assembly and packaging” — and not other points in the process, like shipping. It also may not cover material production.

Shipping information obtained by the SOMO Center for Research on Multinational Corporation indicates that Roots merchandise purchased by Canadian companies may have passed through the Yantian port in Shenzhen on the southern coast of China, and Ningbo port in the cities of Ningbo and Zhoushan, China in the Eastern part of the country. The SOMO Center’s information does not guarantee that these items were U of T merchandise, but some products match up with what The Varsity identified on U of T Bookstore shelves. One Roots U of T sweater matches the description of a unisex knitted sweater on SOMO’s list of items that passed through the Yantian harbour.

Both harbours have histories of labour rights violations that U of T’s Code of Conduct for Licensees would not cover, because shipping does not fall under the “manufacturing process.” For instance, in 2013, 800 Yantian dock workers walked off the job because their companies were withholding their benefits from them, and in 2014, thousands of truckers at the Ningbo Port went on strike due to poor working conditions.

U of T’s Code of Conduct for Licensees would also not cover working conditions during the materials production phase that violate the university’s policies.

Most U of T merchandise examined by The Varsity was produced in Pakistan, followed by China, whose northwest Xinjiang region produces a fifth of the world’s cotton. The area is home to 12 million Uyghur Muslims, and researchers have implicated China’s federal government in subjecting the Uyghurs in Xinjiang to forced labour, including a vast apparatus of prison camps and forced cotton picking.

Aidan Chau, a researcher at the Hong Kong-based China Labour Bulletin — an organisation that monitors labour conditions — told The Varsity that forced labour in Xinjiang focuses primarily on cotton production and not on manufacturing. Chau added, “if you’re really focusing on forced labour, I think the areas that you would like to see is where they’re sourcing the cotton from.”

How does this play out in the real world?

Even though U of T declined to provide a list of merchandise manufacturing locations, there are still indications that producers of U of T merchandise do not follow the labour standards laid out in the school’s Code of Conduct for Licensees.

Many of the U of T-branded garments that The Varsity examined are produced in countries where manufacturers cannot adhere to U of T’s Code of Conduct for Licensees.

For instance, the ninth requirement of U of T’s Code of Conduct is the right to democratic unionization. However, U of T merchandise is produced in two countries — China and Vietnam — where, according to Han, “The political regime just means that free and fair trade unions are not possible.” Both countries forbid independent unions, instead having one main workers’ federation that exists as an instrument of state control.

As Chau told The Varsity, all unions in China exist under the umbrella of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions. “There’s basically no independent unions in China… if they have unions in a company, most are organized only through cooperating with management,” Chau said.

Similarly, in Vietnam, all official trade unions are led by one state-led union organization. New legislation in 2021 permitted “Workers Organizations,” which cannot represent a workforce beyond a single company. Workers Organizations are more limited in autonomy than unions. Additionally, members of Workers Organizations still do not have rights such as freedom of speech.

U of T merch produced in China includes Champion sandals, Creature Comforts Toys stuffed animals, Legacy touques, MV Sport jackets, Roots sweatshirts, and various Varsity Collection items. Nike sweatshirts and pants, adidas pants, and Under Armour sweatshirts are among the merchandise items produced in Vietnam.

When The Varsity asked U of T why they produce merchandise in countries, like China and Vietnam, in which it is impossible for manufacturers to follow the Code of Conduct for Licensees, a spokesperson wrote, “Pulling out of a region in its entirety does not always benefit the communities and the workers within those countries and regions.”

U of T’s Trademark Licensing website writes, “The program’s main goal is to ensure the University and its departments are engaging in ethical procurement of merchandise.” Another sentence reads, “It shall be the responsibility of each University licensee to ensure its compliance with this Code, and to verify that its contractors are in compliance with this Code.”

Activism for accountability

In an interview with The Varsity, Brian Sharpe — a former SAS activist and one of the protesters who participated in the 2000 sit-in — remembered the 10 days he spent holed up with friends, reporting to indie radio outlets, and planning out future SAS actions “not just on campus, but also in Toronto, and in the region.”

However, Sharpe explained that the spirit of the protest eventually fizzled out.

“Students Against Sweatshops continued at least for another year or two,” Sharpe remembered. However, “it was tiring work [lobbying] the administration, trying to hammer out details around how the policies were worded.”

“That’s not exciting for a large group of activists,” Sharpe said.

Despite the decline of U of T’s SAS chapter over the past 20 years since its sit-in, others see the potential for student activists to incite change.

“Students have historically had a really important role in this work,” Champagne said. “[They] have been the moral voice in the campus community, calling for improvements in these factories [and they] have a great opportunity to be part of these conversations on campus.”