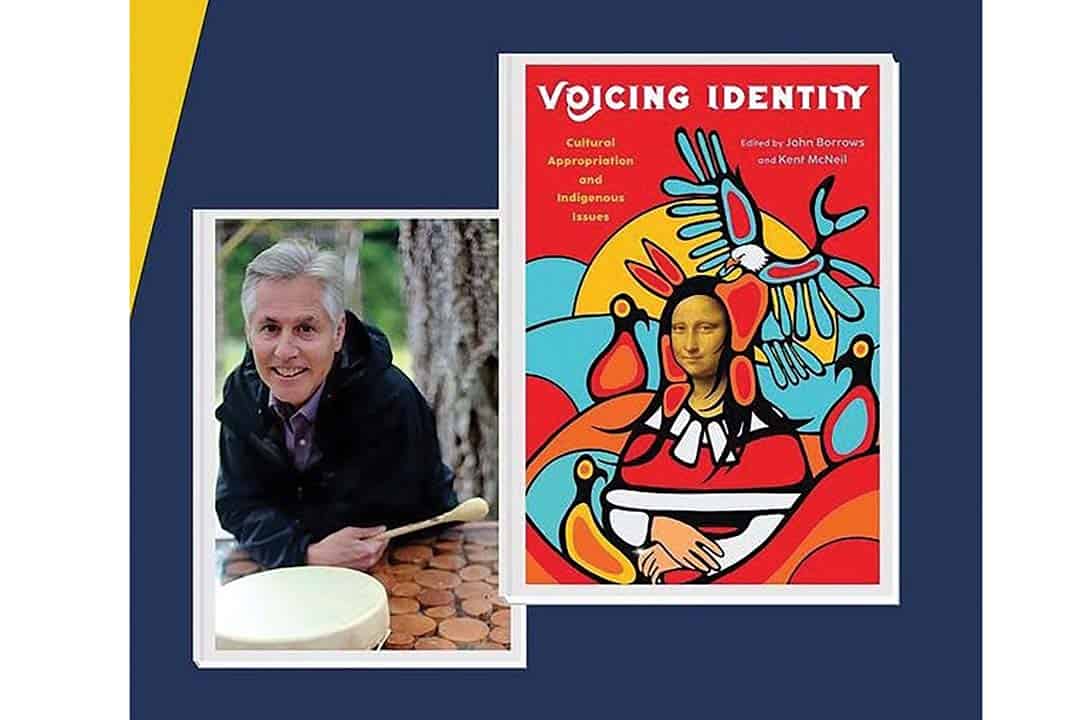

When I sat down in the law building’s impressive atrium for John Borrows’ talk on his newest book of essays, Voicing Identity: Cultural Appropriation and Indigenous Issues, I got the impression that I was looking through a window at a deep area of the world that I had yet to learn about: Indigenous law.

Borrows is U of T’s current Loveland chair in Indigenous Law and came from the University of Victoria, where he held the Canada Research Chair position in Indigenous Law. After hearing about the past, present, and future of his research and work, the importance of Traditional Knowledge, whether law or otherwise, is clearer to me than ever.

The past: Family history

Borrows’ own story begins generations ago, as he and his ancestors have had land and legal status as Indigenous peoples for seven generations. According to Borrows, the legal status that Indigenous peoples have was introduced as a concept by European settlers, yet, it is a key part of their identity and maintaining their land. Here we see that, since settlers arrived on Turtle Island, it has been essential for Indigenous peoples to prove their legal positions in the context of a law that is not their own.

Throughout the story of Borrows’ family’s past, Indigenous law manifests as a personal interest not necessarily in law, but in his personal history. His great grandfather, Charles Giganos Jones, was a runner who transported messages between Indigenous nations and between settlers so that harmony could be kept. Borrows’ thesis as a JD, A Genealogy of Law Inherent Sovereignty and First Nations Self-Government, traces this extensive family ancestry. In his own roots, he finds the seeds of strength in the face of legal challenges. His great grandfather was not a victim of the Indian Act as some narratives may suggest; instead, the history shows that he took action and lived by the laws he grew up with — not those imposed upon him.

The present: Voicing identity

The 28th call to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission requires all Canadian law schools to provide a course on Indigenous peoples’ and Indigenous law. In order to do so, schools need reliable information, and they need to balance respectful engagement with Indigenous peoples and issues, given their diverse identities.

Borrows’ new book, Voicing Identity — a collection of 15 essays edited by Borrows and Kent McNeil — responds to this need, providing a window into Indigenous law for students and schools. The essays are written by different academics who reflect on experiences with the law and topics in Indigenous history, such as building relationships to teach substantive Indigenous laws and finding value in your place in the world.

Borrows aimed to make the text accessible to a wide population, instructing the authors to try to “think about the [writing styles of] the New Yorker and the Atlantic” when writing their essays. The result is a book practical for law students, and informative for those looking to better understand the land acknowledgments that we hear everyday.

The future: Preserving knowledge

When we understand Indigenous law, it opens up the door to understanding much more complex relationships between Indigenous peoples and settlers. Borrows’ aspiration with his next work is to create a living history of Indigenous values, to make “all of our [Indigenous] traditions living.”

Ultimately, Borrows’ talk reminds us that Indigenous history will always be part of Canadian law. We must appreciate, learn, and enter into dialogues about that to appreciate and understand Indigenous peoples and respect their traditions.