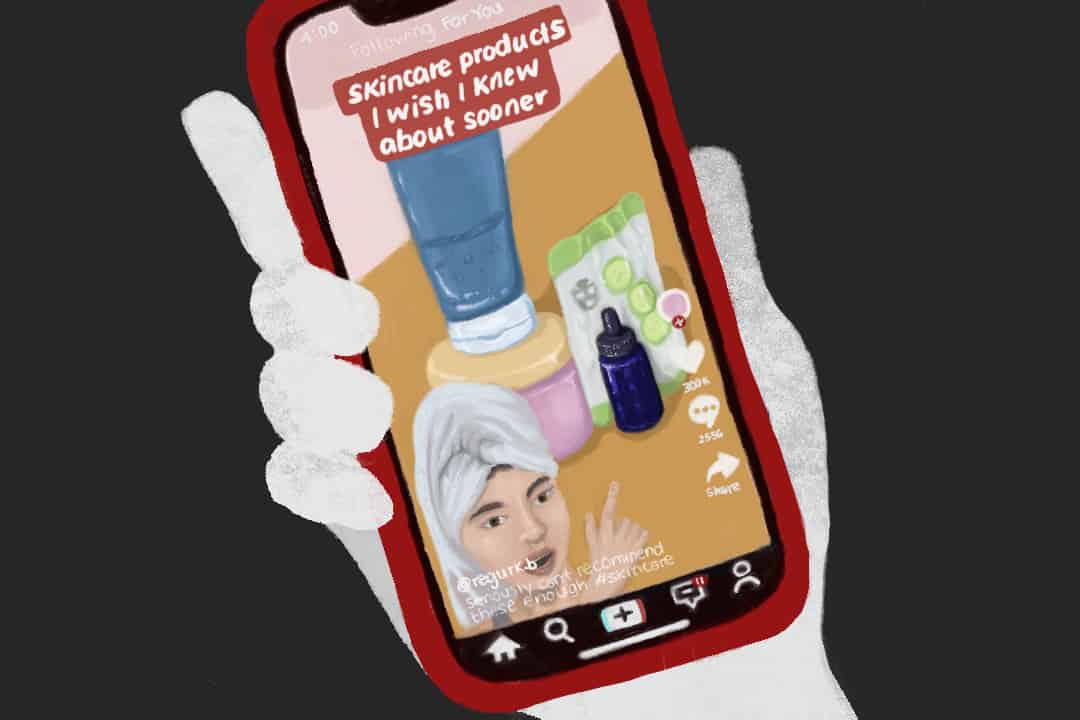

Last fall, a Google vice president mentioned in a talk that, according to the company’s estimates, some 40 per cent of younger people no longer go to Google as their first stop for a search; instead, they use TikTok and Instagram. And I am not ashamed to say that I am part of that 40 per cent. TikTok has become my most used social media app since I downloaded it in 2020, when they rolled out the feature of organizing saved videos into folders. My friends and I rejoiced because we could finally sort through the dozens of videos we saved on places to eat in the city and the best new skin care routines. And us young folks are not alone.

Several companies have realized the potential that TikTok videos have and the real material change that can result from going viral on the platform. The algorithm pushes a feed that is uniquely suited for each person and prioritizes novelty and retention, meaning that your experience is wholly yours and there is a sense of trust, since the content is made by regular people, just like you.

Almost everyone I know uses TikTok because it feels untainted by the world of marketing — there’s the appearance that you’re getting someone’s true unfiltered opinion, an escape from YouTube ads and Instagram’s increasingly monetized feeds. When we go on TikTok, we are seeking the truth; which is of course an illusion.

Marketing and advertising companies were quick to jump on the potential of TikTok, and in industries where it has been particularly revolutionary — publishing for example, as evidenced by the continuously growing and ever present TikTok table in every Indigo — the platform has even partnered with giants such as Penguin Random House to roll out exclusive features allowing ‘BookTok’ creators to link Penguin Random House publications directly to their followers, while links are usually notoriously finicky on the platform.

Of course the power is not completely one sided; BookTok influencers have also demanded more diversity from publishers and have raised awareness and shown solidarity for Harper Collins workers striking for better wages, to the extent of refusing to review any Harper Collins books while the workers are striking.

And yet, there is still an element of relatability and awareness that permeates TikTok compared to other social platforms — a sense that it is less curated even though the algorithm is famous for being very specific. This inherent paradox has led to a new trend: ‘deinfluencing.’ The trend started as a justified critique of the way social media pushes products down consumers’ throats. Overnight, there seemed to be this growing consciousness of our increased consumption, and of the dystopian nature of phrases such as “TikTok made me buy it!” But then it all came crashing down.

Almost as quickly as the trend started, it morphed into people sharing their negative reviews of popular products and even recommending alternatives that they thought were better. The focus diverged from the need to reduce our consumption, becoming a better shopper, to not falling for the marketing gimmicks of certain trendy products and instead, buying other lesser known and better ones. The issue is no longer that you’re buying something you don’t need — it’s that you’re not buying the best, cheapest, most worth-it things you don’t need.

But why? Why is it that a trend conceived to go against overconsumption gets twisted so effortlessly and so quickly into one for more efficient consumption?

Part of it is the nature of content on TikTok itself. The short-form videos combined with the algorithm leads to an experience that is immersive with the sole goal of keeping you on the app. The continued and increased exposure to reviews acts as a sort of confirmation bias, reaffirming your desire for the product.

But there is also a more subconscious and sinister reason behind this. In an essay that has become infamous on the internet, New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino writes about how the “ideal woman” has become a mirage that is increasingly harder to capture, at least in the traditional sense. According to her, the internet and consumerism have driven women to always be chasing the idea of their “ideal self” to optimize themselves. At the center of this optimization process is buying — buying the best makeup, the most advanced skin care products to reverse the tides of time, or tickets to the most expensive workout classes.

Tolentino hypothesizes that instead of breaking down the need to be someone other than ourselves, we have simply morphed that desire into something more socially acceptable under our “post feminist” zeitgeist. We don’t want adverts with models and photoshopped celebrities; we want real people, telling us how a $40 water cup with a straw will lead to a more hydrated, healthier, more beautiful us. How pilates will transform our bodies, how this skin care product will make us look years younger, and how we need, need, need all of this in order to be the best version of ourselves that we can be.

And her essay does specify women, which is not a misguided specification. The cycle of increased consumerism on TikTok is evidently gendered, as are the products that it pushes: make up, skincare, romance books, and shapewear. These items in a vacuum are not strictly for one gender, but one cannot help but notice that women make up the majority of people doing these reviews and the majority to whom these reviews are being pushed. After all, researchers have shown that women drive 70–80 per cent of consumer decisions in the US. There is a benefit in marketing toward women and tapping into the market of over half the population.

All these factors make stopping impossible; we live in a society that pushes products and feeds on the idea that these products are what can make you a better version of yourself. When people are buying, they are not simply purchasing a product — they are taking the first step toward the person they want to be. That image and that strong spell needs to be broken. We are in a cost-of-living crisis, inflation has been steadily rising, and people are unable to afford necessities worldwide, all while corporations see record-breaking profits.

But we are not completely powerless in this equation. The cycle of over consumption can be halted, if not completely stopped. It requires us to take a step back, to evaluate whether we are consuming something we truly need — and if we can even afford it. It requires us to look inward, for what will truly fit into our lives, instead of outward to a mystic truth, a magical product that would make everything better. After all, the first word in the age-old adage is ‘reduce.’