Humans love stories. Far before moving pictures and writing, fiction existed in the forms of oral storytelling, dances, and dramas. Unfortunately, unlike paintings and books, these forms couldn’t fossilize for us to examine.

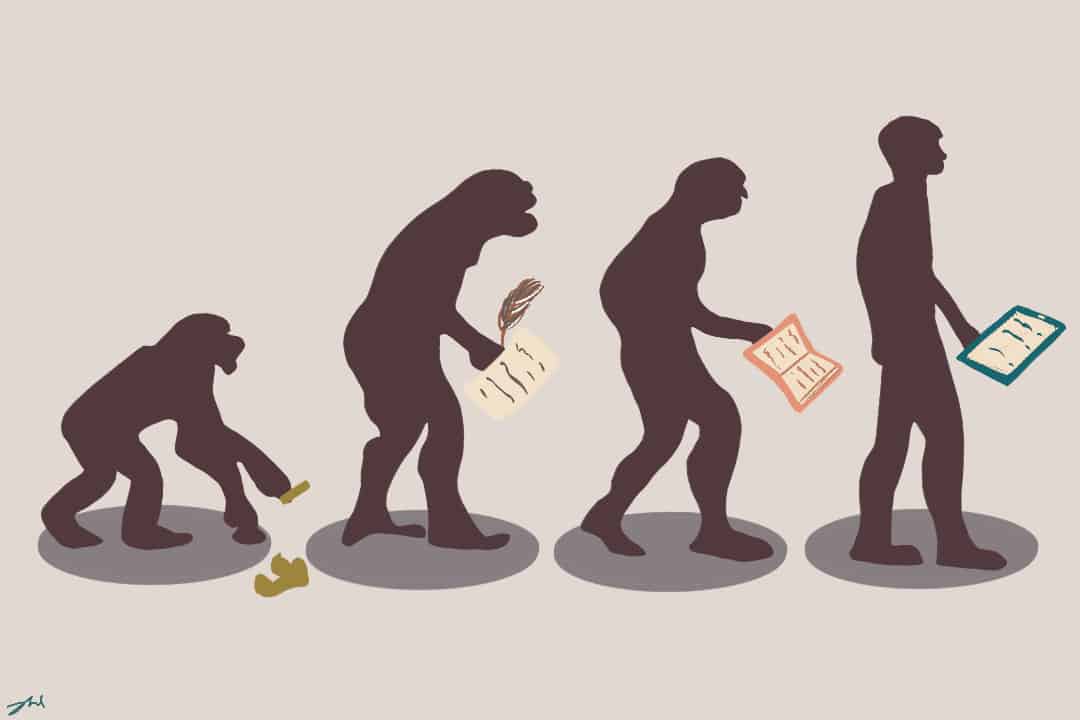

Whereas the oldest surviving work of literature, the Epic of Gilgamesh, was engraved on ancient Babylonian tablets about 4,000 years ago, the cave paintings in sites like Chauvet and Lascaux in France that depicted rituals, hunting practices, and volcanic eruptions, were likely accompanied by oral storytelling and are estimated to be from around 30,000 years ago.

Considering that evidence suggests Homo sapiens — who are not even the oldest human species — appeared around 190,000 BCE, there’s a large gap in our history of storytelling. Nonetheless, scientists have deduced two evolutionary advantages of oral storytelling using various sources.

Survival of the wittiest

Just like birds who sing beautifully, good storytellers may be more likely to attract mates. This is especially true for heterosexual men. In a 2016 study, researchers reported that women rated good male storytellers as more attractive than poor storytellers as long-term partners and perceived them to have higher status, be more capable of leadership, and be more admirable.

In turn, storytellers’ enhanced ability to score a mate may lead to an increased likelihood of offspring. In a 2017 study in Nature Communications, anthropologists found that in the Agta community — a hunter-gatherer population in the Philippines — those identified as skilled storytellers had higher reproductive success. On average, skilled storytellers had 53 per cent more living children than others.

According to the researchers, skilled storytellers’ higher reproductive success may be because others in the community were inclined to look favourably at the storyteller’s family and extend their help. Skilled storytellers were found to be nearly twice as likely to be chosen as preferred campmates than others. They were even chosen over people who had equally good reputations for hunting, fishing, and foraging. The study also found that the presence of good storytellers in communities led to increased cooperation. This isn’t to say humans prefer a good story over loads of food. Rather, it indicates that storytelling may have an equally adaptive value to human life.

The researchers also found that, in a resource-sharing game, skilled storytellers were the likeliest to be recipients of rice. The researchers theorize that this outcome may correspond to real-life benefits for storytellers from community members, such as food, assistance with childcare, or access to other resources that contribute to their well-being and survival.

Two heads are better than one

Since our ancestors evolved to live in groups, they likely used storytelling to gather and communicate information about their environments and increasingly complex social relationships.

Stories served as a way to make sense of the world and its benefits and dangers. The use of narratives allows people to remember information far more than facts alone. Thus, stories allowed our ancestors to transmit and remember important information about their environment, such as where to find food and water, and how to avoid dangers, such as predators and illnesses.

In addition to practical knowledge, stories also helped to establish social norms and behaviours. In the same 2017 Nature Communications study on the Agta, researchers found that camps with a greater proportion of skilled storytellers were also associated with increased levels of sharing. The likely reason? 70 per cent of the Agta’s stories conveyed norms and principles regulating social behaviour, such as those in regard to sex equality, friendship, group identity, and social acceptance.

By imparting clear and memorable lessons on how to coexist and cooperate with others, stories can create a culture of social harmony, in which individuals share similar values and resolve conflicts peacefully.

Tribes to civilizations

As humans developed more complex societies, storytelling also played a critical role in shaping their beliefs and values.

With the developments of agriculture and written language, people needed less time to teach and learn the basics of survival, and more time could be spent on understanding the physical world and our abstractions. Humans could grapple with questions about natural phenomena like the weather and the sun, moon, and stars, as well as existential questions about purpose, fate, and higher powers.

In his 1976 book The Selfish Gene, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins coined the word ‘meme’ to describe a “unit of cultural transmission.” Memes, he wrote, could be any product of human intellect — such as ideas, tunes, or aesthetics — and are similar to biological genes in that they carry information, replicate, transmit from one person to another, and mutate at random, all while serving their own, ‘selfish’ ends. In that manner, all stories are memes.

Stories evolved into myths, legends, and religious narratives — engaging and dramatic memes that often followed similar structures and espoused similar themes — to explain the mechanisms of nature and guide people’s moral and spiritual thinking. By telling and retelling these stories, people could reinforce their shared beliefs across generations far and wide, as well as reinvent and adapt to newer cultures.

Larger societies, now sharing a framework for understanding the world, could then use stories to organize themselves, work toward common goals, and function efficiently. Today’s world largely functions and cooperates because of the story of money.

United we stand, divided we fall

Unfortunately, some have applied Charles Darwin’s ‘survival of the fittest’ evolutionary theory to societies, which means that societies with different ideologies may use their stories as justification to dominate others, or merge stories as a means of assimilating and diminishing others.

European colonialism often operated on stories that white, ‘civilized,’ and Christian societies were superior to racialized cultures of different religious or spiritual beliefs and practices. More recently, the term “cultural appropriation” signifies that certain practices are mutated to fit the interests of a dominant group, losing the nuanced, culture-specific narrative behind them. Meninists and right-wing groups often co-opt well known feminist and left-wing slogans to disseminate their ideologies, while proponents of Adam Smith’s free market and Karl Marx’s communist theories have been fighting about capitalism and communism for decades, disagreeing on how and why we should work for money.

While stories were once cause for celebration for their benefits to human evolution, they’re now in a precarious position. Whether the power of storytelling can lend to further development of human life, or limit it, is something only time can tell.