As humans, we consider ourselves an elite species, capable of a great number of fantastic feats. We have been to the moon, built nearly kilometre-high buildings, and can complete 100 metre races in almost nine and a half seconds. Looking at the complex processes that occur in the human brain, even the simple task of walking to class seems impressive.

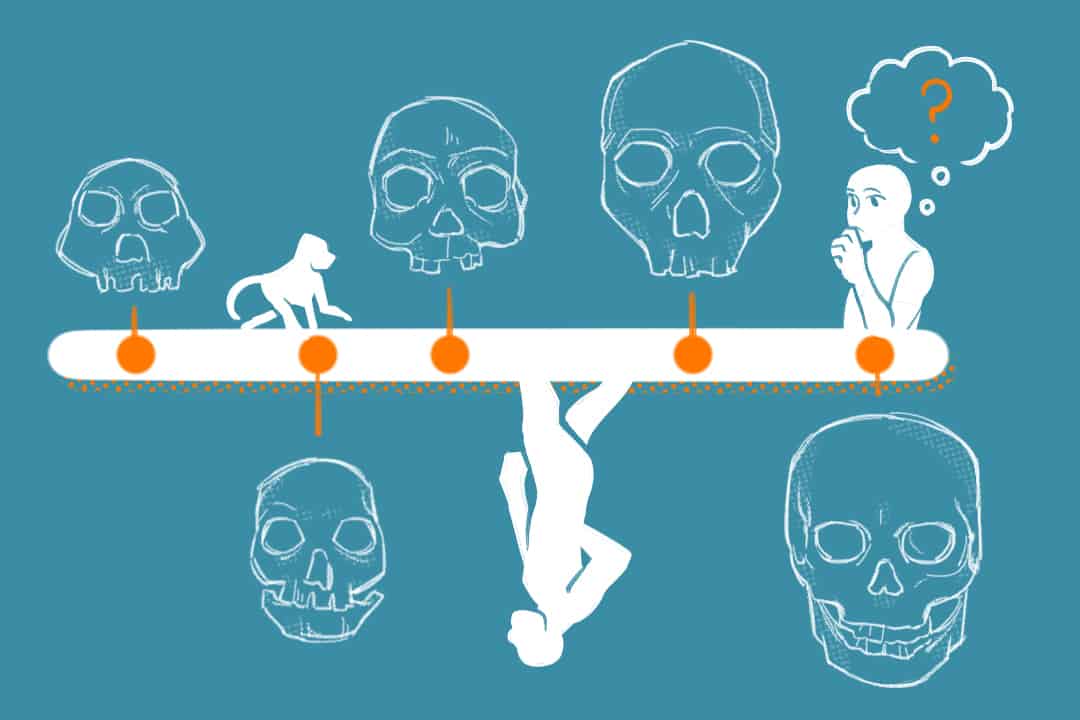

We know that this refinement didn’t just appear: the Homo sapiens that we know are the products of six million years of evolution and evidence suggests that eight major human species, which we will explore, are divided by region.

Africa: the ancient home

Let us introduce the first species of the genus Homo, Homo habilis. This species evolved from apes approximately 2.4 million years ago, and was discovered by a team of researchers who discovered fossilized relics in Tanzania. Indeed, this species was notably different from humans today, featuring smaller frames — typically, 70 pounds and under five feet — and larger braincases.

While H. habilis indeed assumed a primate-like figure, based on the visibility of Broca’s area — a region of the brain essential for speech production — in fossilized brain casts, researchers hypothesize that this species may have been capable of rudimentary language.

Today, we dub H. habilis “handyman” with the knowledge that these species made complex tools for survival and nourishment, such as using stones for butchering animals, and thus began the long and slow process of human invention, from the basic to the extraordinary.

Today, it is widely understood that this species went extinct in part due to the inability of their technology to evolve and subsequently adapt to environmental change.

Next is the far more researched H. erectus, which evolved 1.89 million to 110,000 years ago in Africa before spreading into many parts of Asia. As the name suggests, this species was the first of the Homo genus to stand erect — fully upright — resembling modern human proportions more than their H. habilis ancestor and those of apes.

However, unlike apes, H. erectus developed long legs for running and shorter arms, as well as a notably large braincase and smaller teeth. The latter feature certainly aided the species in eating meat and helped them consume the necessary nourishment to develop more complex and adaptive brains and bodies.

Scientists even discovered campfires near the species’ remains, which is direct evidence that H. erectus were the first Homo species to experiment with cooking. Understandably, this species was relatively successful and existed on Earth for a period close to ninefold times longer than modern humans have up to today.

Like their ancestors, unfortunately, H. erectus seemed ill equipped to deal with drastic climate variations. For those who survived, a potential ‘mass death’ from a volcanic eruption may have eradicated the remaining individuals in this species in the last 10,000 years.

Around 1.9 to 1.8 million years ago, Homo rudolfensis walked the Earth, although we know very little about the species. The hominid was discovered near Lake Turkana in Kenya and had a larger braincase than apes and H. habilis, as well as recognizable pelvises and shoulders, which provides good evidence that this was a human species. Competition for resources with their more advanced relatives likely eliminated this archaic human species.

Finally, in South Africa, some 335,000 to 236,000 years ago, the Homo naledi hominids walked the Earth. An expedition in 2015 showed that this species had a smaller stature of under five feet, but we know little else, in spite of the remarkable number of specimens collected from the species. Researchers postulate that H. naledi was the first human species driven to extinction by us, the H. sapiens.

Europe: migration and adaptation

We know little more about Homo heidelbergensis, which evolved 700,000 to 200,000 years ago in Europe and eastern Africa and were the first humans to live in cold regions. This species resembled wider and smaller humans and were the first to use spears to hunt large animals and build shelters for warmth and protection. Further, the location of this species is important. Researchers contend that H. heidelbergensis of the African branch is the species that instigated the emergence of H. sapiens.

The primary reason why this species no longer walks the Earth is their inability to adapt to rapidly changing ecosystems that were vastly different from the African climate human species had known thus far.

And now, we present the species that we are likely most familiar with: Homo neanderthalensis, or neanderthals. Neanderthals emerged some 400,000 to 40,000 years ago, originating in Europe and Asia. The stature of this species was not unlike our own, only shorter and sturdier with bigger brains.

This species built sophisticated shelters and fires and used needles and other complex tools to make clothing. Most remarkably, we begin to observe complex cognitive processes in this species, with evidence of marked graveyards, all of which suggest that Neanderthals buried their dead and even conducted rituals that we associated with empathy and grief in modern life.

Contemporary research extracts DNA from H. neanderthalensis to examine specific characteristics of this species and has found some startling connections between them and humans today. It is possible that, at one point, H. sapiens and Neanderthals mated, merging parts of our gene pool until individuals with traces of neanderthal DNA were indistinguishable from H. sapiens.

Asia

As we approach the existence of modern humans, we come across another species that evolved some 100,000 to 50,000 years ago, Homo floresiensis. The discovery of this species has been essential to determining the extent of human migrations, as its uncovering on the Island of Flores, Indonesia in 2003 revealed its isolation.

Research on insular dwarfism has led to the hypothesis that, the smaller a habitat, the further an animal will reduce its body size, and H. floresiensis exemplified this concept. Recent findings also revealed that this species used small tools for hunting other diminutive animals. Unlike climate and ecosystem changes that wiped out many other humans, volcanic eruptions are the most likely cause for wiping out H. floresiensis.

The eighth major species in the genus is Homo luzonensis, which evolved at least 67,000 years ago and whose remains were unearthed in an isolated cave in northern Indonesia in 2019. Researchers found few intact fragments but were intrigued by the species’ geographic seclusion. The science behind this particular species is somewhat elusive compared to the other geographically isolated species in the genus, such as H. neanderthalensis and H. florseinsis.

As to where they went, a combination of changing climate and the arrival of H. sapiens drove H. luzonensis to extinction.

Emergence of the modern human

And now we come to the talking, over-thinking, moon-visiting, internet-creating, Velcro-inventing species you are likely acquainted with. As you might have gathered, our evolution and creation has taken an extremely long time and the evolution of many different hominids. H. sapiens have been evolving in our subset for the last 300,000 years, with variations of language emerging 150,000 years into that evolution. This species emerged from a few locations across Africa, with various groups interbreeding with other members of the Homo genus. This diversity has contributed profoundly to the success of humanity today.

You might be wondering why H. sapiens are the only surviving member of the genus — indeed, for most of this species’ existence, many of the Homo families described above roamed the Earth. Indeed, we have been portrayed as a rather cruel species, responsible for wiping out at least three of our ancestors and genetic relatives. It was only around 40,000 years ago, following close to six million years of the species’ existence, that research suggests the H. sapien species found itself alone on Earth.

While the delineations aren’t clear, researchers in this area have proposed that a combination of environmental circumstances, potential interbreeding of species, and competition and biological differences, such as larger brains, explain why we remain on Earth instead of one of our capable ancestors. Our complex ability to explore, survive unprecedented changes, and build technological marvels have resulted from millennia of evolution. Despite this information, it is not far fetched to reason that, perhaps, our existence will always remain a mystery.