Have you ever wondered why you’re drawn to certain people? Is it their eyes? Their outfits? Their personality?

Picture this: a hidden code within your immune system, influencing who you’re naturally drawn to. Here enters the major histocompatibility complex — the unsung hero orchestrating the body’s defence and, as it turns out, a key player in the intricate game of love.

Decoding human mate choices

To start, understanding human mating choices proves to be a complex endeavour, as it’s intricately woven with cultural influences, personal preferences, and biological factors.

Cultural influences play a significant role in shaping human mate choices. Throughout history, societies have developed norms and expectations regarding whom individuals should choose as their partners and often dictate certain characteristics that are deemed desirable in a partner, in terms of physical appearance, social status, or financial stability.

Personal preferences also contribute to the complexity of human mate choices. Each individual has unique desires and needs when it comes to finding a suitable partner. Some may prioritize intelligence or a sense of humour over physical attractiveness or financial stability. Personal experiences and values also shape these preferences, making each person’s criteria for choosing a mate highly subjective.

Biological factors can further complicate mate choices as well. Evolutionary psychology suggests that certain traits can be attractive due to their association with reproductive success. For instance, some men may be drawn to women with signs of fertility, such as an hourglass figure, because these traits indicate potential for healthy offspring.

Unveiling the immune system’s secret to attraction

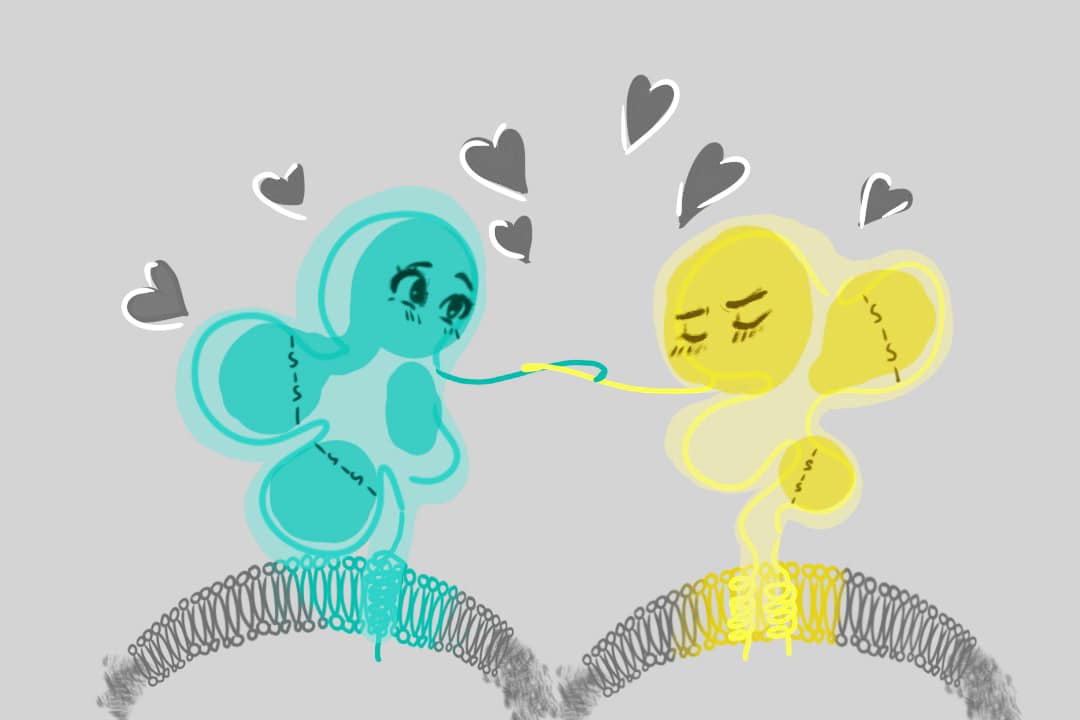

In a body composed of intricate organ systems, tissues, and cells, the genes that make up the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) stand as a guard against invaders. Acting as the body’s immune system orchestra conductor, the MHC molecules help immune cells recognize and combat invading pathogens. They also offer a potential avenue for therapeutic interventions as recent studies have unravelled a fascinating link between our selection of a life partner and that partner’s dissimilarity in a set of genes encoding the MHC.

Studies across various species indicate a common trend: a preference for mates with different MHC genes compared to their own. The mechanisms of this preference involve olfactory cues, suggesting that animals can detect these genetic differences through scent. This instinctive choice enhances the chances of producing offspring with a diverse MHC, providing better resilience against a variety of pathogens.

Surprisingly, humans can also differentiate MHC-related odours, though the exact way that works is up for debate. Many vertebrate animals have an organ dedicated to this sense of smell called the vomeronasal organ. This special organ is in the nose and is particularly good at detecting pheromones released during social and reproductive behaviours, such as those emitted when an animal wants to mate.

On the other hand, humans have cells called receptors in their noses that are used for communication through scent. Researchers are still curious about how our noses guide our preferences, especially with body odours. A 2016 Dresden University of Technology study showed evidence that the women who participated seemed to consistently lean toward the scents of men with diverse MHC genes. It’s like our noses are wired to find diversity attractive, adding a whole new layer to the mystery of human attraction.

Potential evolutionary advantages

As researchers explore MHC-based mate selection in humans, a tapestry of potential evolutionary advantages emerges. Particularly, MHC-dissimilarity may help enhance disease resistance in offspring by increasing immune system diversity, improving fertility rates, and causing greater sexual attraction and satisfaction.

First, by choosing partners with different MHC genes, individuals increase the chances of their children inheriting a diverse range of immune system genes. This diversity provides offspring with a robust immune system, less susceptible to a wide array of pathogens, particularly in environments where infectious diseases are prevalent.

Moreover, a 2016 study by Pablo S. C. Santos and colleagues indicates that couples with dissimilar MHC profiles will likely produce offspring with higher genetic fitness compared to couples with more similar MHC profiles. Choosing a partner with dissimilar MHC genes may also act as a safeguard against inbreeding depression, which refers to the reduction of the survival and fertility of future generations of offspring in cases of inbreeding.

Finally, as a result of the need for differentiating MHC genes, humans exhibit a preference for the body odours of partners with dissimilar MHC genes. This preference, the 2016 Dresden University of Technology study suggested, added to greater sexual attraction and satisfaction within relationships. Additionally, partners were more dissatisfied with their sexual relationships when their MHC genes were more similar.

Altogether, these potential benefits suggest that the consistent pattern in mating preferences for MHC-dissimilar mates isn’t merely a matter of instinctual choice; it’s a survival strategy.

While evidence from that 2016 study suggests that MHC influences animal mating preferences, generalizing these findings to humans is more complicated — the intricacies of cultural, societal, and personal factors intricately weave into our mate choices, challenging the simple conclusions we may be tempted to draw.

And so, the question persists: are we truly wired to choose mates with dissimilar genetics? The answer may well reside in the intricate dance between nature and nurture, a dance that continues to captivate scientists, researchers, and curious minds alike.

No comments to display.