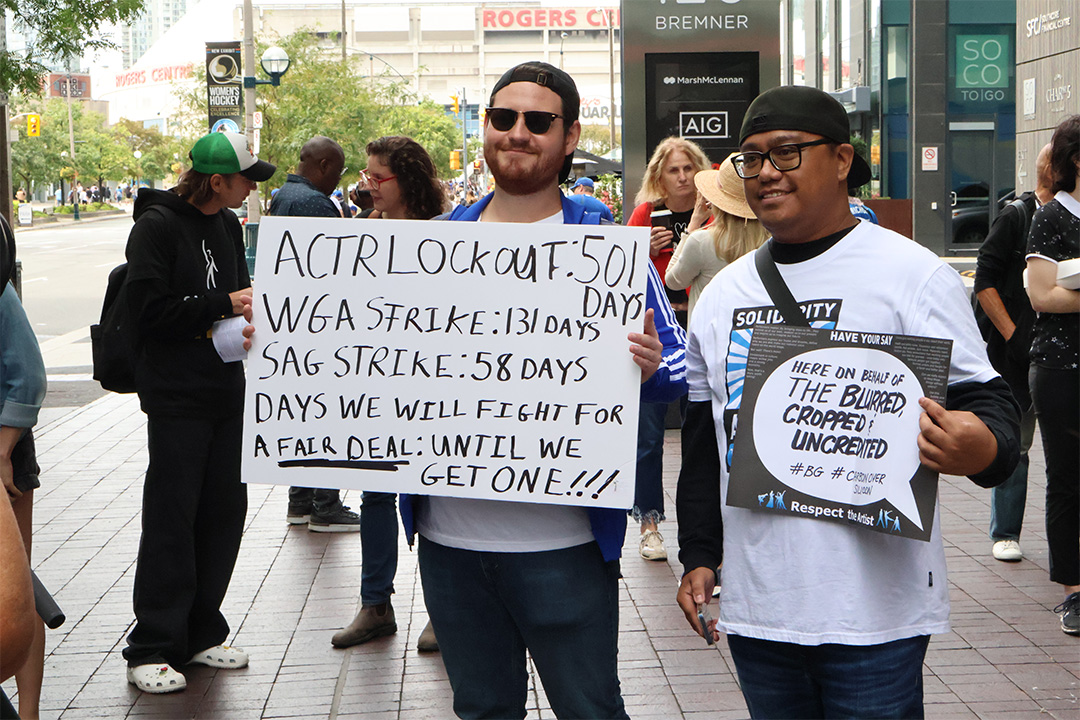

While the glitter and glamour of TIFF has been plastered across the front lines of newspapers this past weekend, the current film hype conceals a deeper story going on behind the scenes. On September 9, the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists (ACTRA) and the Screen Actors Guild–American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) held a joint rally outside of the Amazon and Apple headquarters to vocalize their joint concerns.

Despite the similar looking names, ACTRA and SAG-AFTRA are two different unions — the former is specific to Canada, while the latter primarily focuses on the United States.

ACTRA represents over 28,000 members in different provinces across Canada and acts as the foundation of performing arts labour in the country. Professions of ACTRA members vary, ranging from actors to comedians to stunt doubles. The union works to safeguard jobs and work opportunities for Canadian actors through lobbying the government and collective action.

The demands

While the crux of the two groups’ concerns — job security and better compensation — are similar, the specificity of their situations is very different. SAG-AFTRA has been on strike for over 60 days, calling for a new contract with Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers protecting actors against the use of artificial intelligence (AI) trained on their images.

“The terms and conditions involving rights to digitally simulate a performer to create new performances must be bargained with the union,” SAG-AFTRA wrote in a statement on its website.

Members also call for better compensation amid the streaming revolution.

Meanwhile, ACTRA staged the September 9 rally in light of the 500 days of commercial lockouts imposed by the Institute of Canadian Agencies (ICA). The lockouts were the result of the ICA’s and ACTRA’s failure to renegotiate their deal on Canadian actors appearing in advertisements.

For the past 60 years, the two groups have regularly negotiated agreements under the terms of the National Commercial Agreement, the agreement that establishes the rules around English-language commercial production in Canada. But they reached an impasse in April 2022 over questions of foreign ad agencies producing ads in Canada using unionized workers.

ACTRA has filed a complaint with the Ontario Labour Relations Board, accusing the ICA of negotiating in bad faith by jeopardizing the union instead of working to reach a workable agreement.

In an interview with The Varsity, Eleanor Noble, the National President of ACTRA said, “During our negotiation, they decided to lock us out… They wanted to gut our agreement, cut our wages by 80 per cent. And we said no, and when we said no, they just locked us out.”

The ICA disputes this framing. “Much of the ACTRA rhetoric is simply not true,” the organization wrote in a fact sheet published on its website.

Demonstrators planned the rally’s location strategically. ACTRA member Jonah Hundert called out Amazon and Apple — who own the streaming offshoots Prime Video and Apple TV respectively — for “trying to take away the livelihood of working artists.” During the protest, some of the demonstrators took the ACTRA flag and used it to cover the shiny silver Amazon logo displayed at the front of the building, blocking out the letters.

The long fight ahead

Being locked out of a commercial jurisdiction by the ICA means that countless ACTRA actors don’t have a place to showcase their work. This includes 28-year-old ACTRA Toronto member Dewey Stewart, who studied acting at York University. In an interview with The Varsity, he stated that the best way for viewers to show support during these times is to continue consuming art.

“Go see movies, watch TV shows, and keep on ingesting art because the more you do that, the more they understand that this is a very vital and needed fight.” Stewart stated that the true value of a production comes from its actors, writers, and theatrical and stage employees instead of its funders. Supporting show business, Steward argues, is the best way to demonstrate that fact to corporations.

When asked whether or not he sees an end in sight to the strikes, Stewart mentioned an interview from Deadline, in which a studio executive stated that he wanted the strike to drag on long enough that “union members start losing their apartments and losing their houses.”

But Steward says that sentiment does not phase people in the industry like him: “Artists are built to fight. We’ve been fighting since day one just to get the job.”

No comments to display.