Life is full of questions. Whether they can all be solved has been debated for centuries and is a source of inspiration for scientists and statisticians alike. Is there a limit to existence? An ending to be found? A mechanism to be understood?

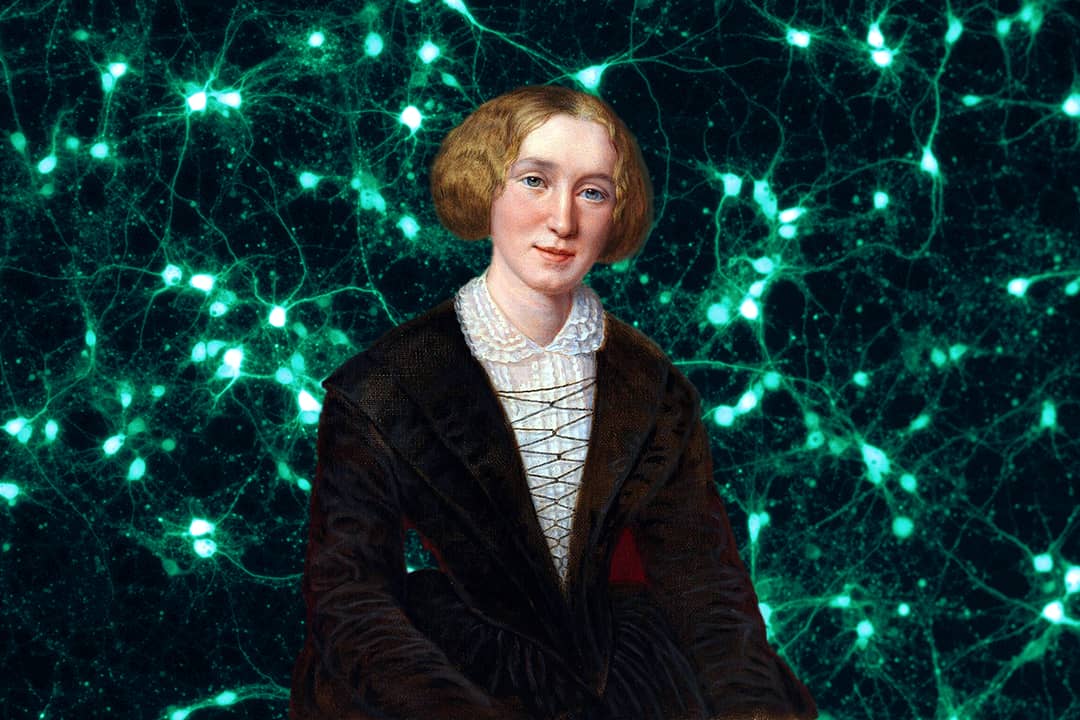

Many in the scientific world have thought themselves capable of reducing life’s complexity to a supreme array of formulae. However, novelist George Eliot, whose work was guided by the individual experience, remained a firm disbeliever of this notion, presuming instead that to be living meant to be ceaselessly beginning. In other words, Eliot believed that life is plastic, easily changed.

Although born as Mary Anne Evans in 1819, Eliot was a woman of many names, each one reflective of her ever-changing identity. During a time that offered women very few freedoms, she changed her name to George Eliot after publishing her first novel. Among her most renowned compositions are Middlemarch and Daniel Deronda, both reflections of her own life in many aspects as well as her convictions about the nature of the individual.

Eliot drew inspiration from the empirical and equally imaginative scientific process, which is centred around finding evidence to prove theories. She wove theories of physics and evolution into her stories. Respecting the ambiguity of biological processes at the time, she believed that human nature is malleable and therefore infinitely free.

Eliot’s philosophy completely contrasted that of many scientists at the time who remained rooted in their search for concrete answers. She essentially supported neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to change with experience, way before its discovery.

A brief history of human nature according to science

In the nineteenth century, scientific debate centred around the question of human freedom, and philosopher and mathematician Auguste Comte’s theory of positivism — the belief that human nature in its entirety could be understood with an empirical approach — reigned supreme. As with religion, it claimed to explain everything regarding the human experience — but with scientific principles, with the rampant, devout support of scientists.

Following Isaac Newton’s theory of gravity, polymath Pierre-Simon Marquis de LaPlace’s “social physics” entered the scene, building off of positivism and purporting that life was as predictable as planetary orbits. Social physics paints the picture of an absent-minded population, strung along by forces with distinct purpose. Any individual deviation from this formula is non-existent, as well as any sense of individuality. LaPlace wrote, “Imagine the present state of the universe as the effect of its prior state and as the cause of the state that will follow it. Freedom has no place here.”

Given the abundance of diversity on the planet, it is a mystery how scientists could have ever considered the human race to be so limited in its existence. Even Newton was skeptical, having written, “I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”

The brain is not fixed, but in a state of constant rebirth

Since then, various experiments have concluded that human nature is far more complicated than previously imagined.

In the past, scientists were convinced that the brain was complete immediately following infancy, suspended from change at the very beginning of life. While many scientists found evidence against this theory, this evidence was largely ignored. It wasn’t until 1998 that neuroscientists found clear enough proof that they could no longer reject neurogenesis — the process of forming new neurons — because of neuroscientist Elizabeth Gould’s experiments on neurogenesis in macaque monkeys.

Gould’s experiments provided compelling evidence that our genes are not the only influence on our being. One experiment focused on two groups of monkey mothers — one housed in enriched enclosures and the other in cages — whose levels of stress correlated to their levels of neurogenesis. The offspring of the caged mothers living in stressful conditions were shown to have greatly reduced amounts of new neurons, even though they themselves never experienced the stress.

Even more miraculous was the discovery that these monkeys’ adult brains rapidly recovered following their transfer to the enriched enclosure. An abundance of new neurons formed in their brains in only a few weeks, demonstrating exactly the malleability imagined by Eliot. In turmoil, our freedom exposes itself as the brain’s incredible potential to be shaped and changed, to be pliable, like plastic.

George Eliot’s plasticity philosophy

Ironically, one could imagine Gould’s female monkeys as a metaphor for Eliot’s life. She was not a complacent woman but conscious of her limited autonomy. Unconstrained by societal norms, transformation was inherent in Eliot’s life.

After her first heartbreak, Eliot became skeptical of positivism, for logic could not explain away her pain, and thus ensued her newfound view of the world. Writing became the means for supporting herself as a single woman, and Eliot, refusing to accept that she would remain imprisoned by her sadness, established an optimism that drew her to George Henry Lewes.

A philosopher and amateur scientist, Lewes believed that our inability to uncover the mysteries of our minds is precisely what constitutes its freedom, and he became one of Eliot’s key influences. “Love defies all calculations,” Lewes wrote regarding his relationship with her.

Would Eliot have come to the same conclusions about positivism had she not experienced turmoil in her relationships? We can never know for certain, but surely a caged woman does not experience as much of life as a free one. Tumultuous events in life bring about emotional upheaval, which, as we have come to learn, is also a turnover of cells. Without periods of transformation, we remain stagnant in our bodies, vulnerable to the same reduction in neurogenesis as Gould’s monkeys.

Even DNA is a story unfolding. Like characters in a novel, we are born from a biological text that is neither predestined nor foreseeable. The story written in DNA dictates our physical being but remains subject to change during our lifetime of exposure to different conditions. Our environment can cause epigenetic changes, which are modifications in how our DNA is expressed, without changing the genetic sequence.

As Eliot wrote, in The Natural History of German Life, “Art is the nearest thing to life; it is a mode of amplifying experience.”

Perhaps the conditions that shaped her more optimistic outlook on life were necessary to fully grasp the concept of neuroplasticity. Our DNA, cells, and neurons do not imprison us but rather set us free when exposed to interpretation. They allow us to change. Science is often portrayed as a means to an end, but we so often forget that it can also signify a beginning.