The mind is not an easy thing to express — it is inaccessible, unpredictable, and ever-changing. Scientists believe the mind holds thoughts, perceptions, senses, consciousness, and awareness. In what science cannot yet explain, the arts provide an interpretation.

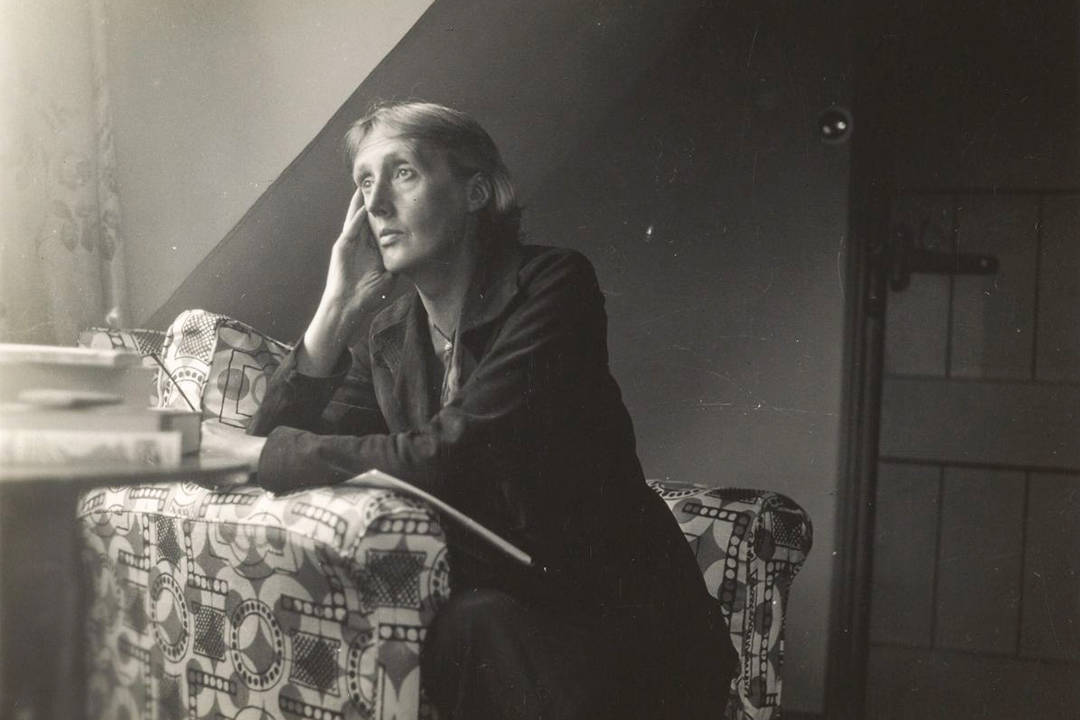

In the early 1900s, it was common to find authors using the conventional omniscient Victorian narrator. But in the 1920s, one author sought to trace the “flight of the mind” through time, along with its untold and unlimited complexities: Virginia Woolf.

Woolf’s written mind

Woolf’s writing style was firmly rooted in her own experiences of the brain and her experiences of mental illness. While staring at the ceiling to pass the time when she was prescribed bed rest, Woolf contemplated her illness, which she described in A Writer’s Diary as the “whirring of wings in the head.”

Woolf concluded that she had — as she describes in A Room of One’s Own — “no single state.” She felt that her mind was fragmented, and yet maintained its integrity. Woolf searched for the glue of our fragile minds — what makes us whole — in her art. Through it, she found the author of our minds and its consciousness: the self.

At that moment in time, scientists embraced materialism — that is, the belief that every phenomenon can be reduced to physical processes — believing that the self was simply matter in the body that was yet to be uncovered. Woolf instead emphasized the profundity of the self, and a century later, the self has still evaded physical characterization by science. This seems only to confirm her original insights that the mind is fragmentary and yet mysteriously bound into being.

For that reason, Woolf’s writing might provide a revealing answer to understanding ourselves and why we have avoided an existence in which we are constantly falling apart. How does the self arise?

The act of attention

In her writing, Woolf documents consciousness as a process. She realized that the self continually emerges from the attention we give to the sensations we experience. We thoroughly interpret the world, but we accentuate some sensations in the mind while ignoring others, and this intersection of sensory information and perspective creates a diverse array of interpretations. No experience is the same for two people — nuance is unavoidable in our attention to our surroundings.

Woolf describes this process of visual attention in her novel, To the Lighthouse, through the experiences of the story’s matriarch, Mrs. Ramsay. During a dinner scene, she becomes lost in thought, her mind finding a “still space that lies at the center of things,” and she becomes captivated by a bowl of fruit in the centre of the table, ignoring the conversation around her. As if her mind is “a light stealing under water,” the cause of these sensations has developed into consciousness: Mrs. Ramsay is paying attention.

The flow of thought in Mrs. Ramsay’s mind is borne from a few seconds of brain activity, as her gaze drifts over the bowl and settles on its specific components. We see how an unconscious urge becomes conscious, as she recalls staring at a pear without a clear reason.

This idea that we invent ourselves out of our unique sensations is not so far-fetched — Woolf’s insights have been confirmed by modern neuroscience. Attention is a crucial component of consciousness and, by some means, these separate moments are bound together by a fictional self.

Consider Woolf’s example of Mrs. Ramsay and a pear on a dinner table. The sensitivity of Mrs. Ramsay’s neurons was increased simply by paying attention to this stimulus; the cells seeing what would have otherwise been filtered out by her nervous system. Jonah Lehrer describes Woolf’s insights in his book Proust Was a Neuroscientist. Similar to a lighthouse shining light outward into the dark unknown, Lehrer describes how this attentiveness selectively“increases the firing rate of certain neurons,” which then bind together in what Lehrer describes as a “temporary coalition” that enters the stream of consciousness. In our choices of how we pay attention, the elusive ‘self’ can induce changes in neuronal firing, “as if a ghost were controlling a machine” — the machine being our minds.

The transformation of perception into consciousness would not be possible without an attentive self. In the absence of neuronal firing, the realities that neurons represent when they’re active and focusing our attention cease to exist. We only become aware of sensations after we’ve selected them for attention, just as Mrs. Ramsay didn’t understand why she was staring at the pear.

A problem with no solution

Many scientists have tried to understand the mind, but Woolf knew that any physical description would be insufficient; we don’t experience our neurons, and our consciousness seems more ambiguous than the sum of our cells. Thus, any reductionist psychologies — which reduce complex phenomena to their fundamental components — seem incomplete, because to define consciousness only by its parts would be to entirely overlook our singular realities.

In essence, our individuality holds an intimacy that science cannot unlock. But it often holds true that artists can describe what science cannot: experience overcomes experiment. Woolf viewed the self as fiction, not fact, and thought that to understand ourselves through fictional narratives would be as close to the truth as we would achieve.

Consciousness is not a place but a process with no end to its progression. To analyze it in search of absolute knowledge would be to ignore its ceaseless subjectivity. Woolf has shown that intangible things can still unveil truths about ourselves. We live in moments — emerging from chaos — to which we choose to give attention.

No comments to display.