In late July, it was time to pick chanterelles — wild, edible mushrooms that I had only heard about in passing. I wandered into the forest and found the first chanterelle, its orange cap wrinkled at the edges like a ruffled skirt, then saw more arranged in what looked like a ring.

As I stepped back, farther and farther, I saw that the “ring” was more like multiple formations, with fruiting bodies peppered between them. I realized that I didn’t know how many beings I was standing on top of — many, or just one?

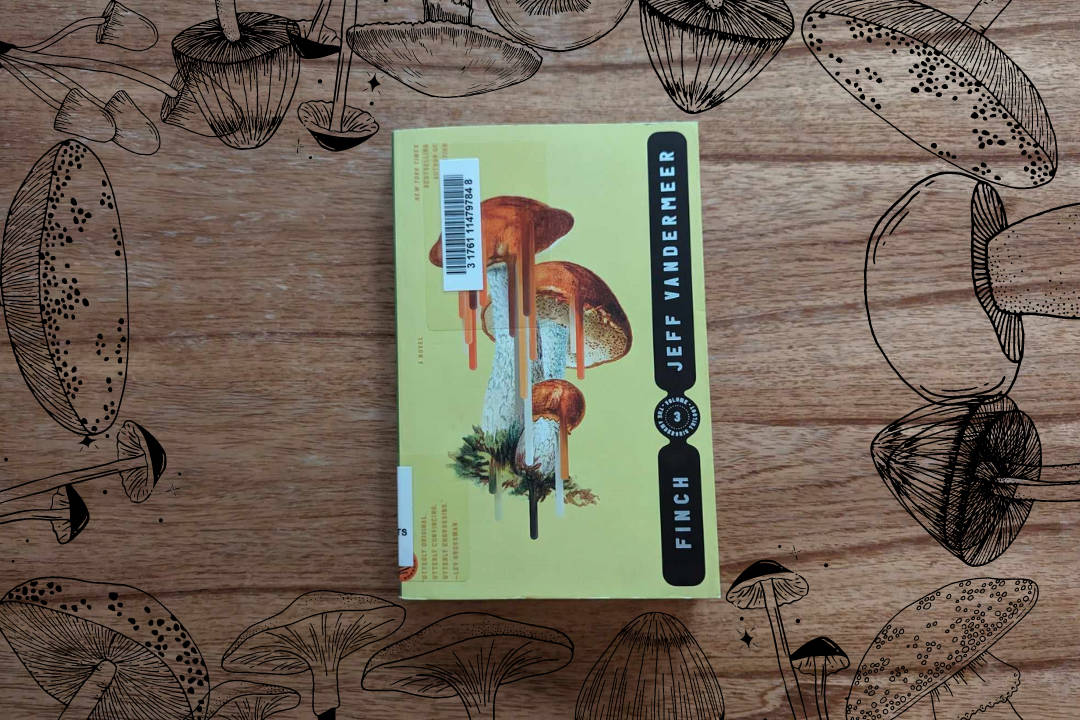

Jeff VanderMeer’s Finch explores the dystopian city Ambergris, slowly decaying under the occupying force of grey caps — mushroom-like people who have harnessed their ability to control spores and weaponize fungi against humans. Like in many of VanderMeer’s other novels, the apocalypse has already happened, and people must continue to do what they have always done — live their lives.

We follow John Finch, a detective solving a mystery who realizes too late that he’s also embroiled himself in the city’s politics. Finch’s narration is often clipped, devoid of subjectivity, and disassociated from his world in a way that makes you feel like he has one foot out the door at all times. Finch was branded as a noir novel, which I’d never previously read any of, so I imagined a noir movie playing out in my head: gritty atmosphere, cigars and whiskey, and spores a splash of technicolour green and gold against the otherwise grim landscape.

In Ambergris, spores hang in the air ready to infect unsuspecting citizens, take over human bodies with purples and greens, and make their flesh spongy. “Partials” — humans who have allowed themselves to be turned into grey cap hybrids — have one eye transformed into a constantly blinking camera. Between the vast underground network and microscopic spores waiting to communicate with their masters, the grey caps’ network seems inexhaustible.

In high school, I learned about the “mycorrhizal network” of a fungus — an underground mat of mycelium, branching threads or hyphae that attach to trees, delivering nutrients to the fungus. Although many of us know fungi only by their fruiting bodies — the fleshy, sometimes colourful, above-ground parts that release spores — the mycorrhizal network is what reveals the true capabilities of fungi. For instance, according to a 2007 article in the Scientific American, a specimen of Armillaria ostoyae found in Oregon in 1998 was possibly the largest living thing on Earth, thousands of years old and thousands of acres large.

Since reading this article, mushrooms have taken on a mythic fascination for me. What was the upper limit of their size? I understood that a lack of available resources would stop an ever-growing fungus in its tracks. But I couldn’t help imagining a continent overtaken by a fungus, finding its spongy mycorrhizal mat under all soil if we just dug far enough. I thought about “saprobes,” the decomposer fungi vital for all healthy soils.

This awe for mushrooms struck me again when I went mushroom hunting last July, breathless at the possibility of one vast organism from which we could borrow nutrients, giving them back when we died.

In the non-fiction book The Mushroom at the End of the World, Anna Tsing asks what it means to cohabitate with other species in the face of mass environmental destruction. She writes about the multispecies worlds that emerge when many organisms make “living arrangements” for themselves simultaneously — these are the worlds, like mycelia branching out, that I think we must be concerned about protecting.

She also discusses the roles of mushrooms, not only in the supply chain but also in culture and her imagination. She focuses one chapter entirely on spores, writing: “Spores take off toward unknown destinations, mate across types, and, at least occasionally, give rise to new organisms — a beginning for new kinds.”

In my imagination, spores stumble into each other, relying on the right gust of wind, numbers, and sheer luck to finally take root — or rather, mycorrhizal network. This bumbling somewhat resembles the rhythm of “Mycelium” by King Gizzard and The Lizard Wizard.

With Tsing’s words about multispecies worlds still on the mind, Finch’s answer to her question about cohabitation is complicated. In Ambergris, not only do humans recognize that they’re in a multispecies world, but they’re also haunted by it. The humans’ oppression by the gray caps is contingent on the reach of spores, the overwhelming size of the gray caps’ mycorrhizal network, and a healthy dose of manufactured fear. On the other side, in our world, humans must reckon with the ecological destruction that they, themselves, have wrought.

At one point, the narration tells us that Finch “didn’t know if he was inside a mushroom or outside the universe.” Our encounters with multispecies worlds, whether thinking about a giant mushroom in Oregon or noticing which trees a certain fungus happens to grow on, remind us that they exist, and how wide-reaching their existance is. Even the tiniest spore is a memento of eons of drifting, settling, and drifting again.

Finally, I return to my question from last summer — were the chanterelles one organism or many? Regardless of the answer, in some sense, I find that their world was far more vast than mine.

No comments to display.