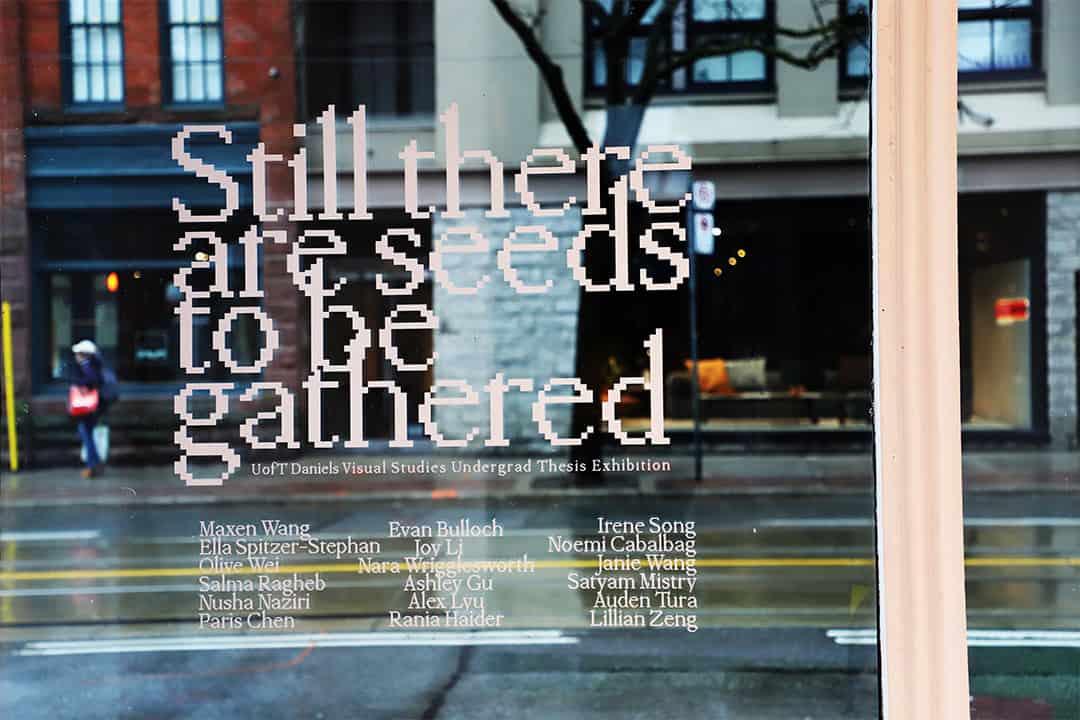

From April 12–14, the Daniels Visual Studies Thesis Exhibition opened at SPACE on King Street East. I went to see the exhibition titled “Still there are seeds to be gathered” for myself on the evening of April 12, a grey Friday on the cusp of exam season. I looked forward to it; after a long week, a bit of intriguing art and a chance to meet some interesting people sounded like a pleasant way to unwind.

When I stepped through the doors of the King Street venue, I saw friends, family, faculty, and artists; a gentle mass of well-dressed, sweetly perfumed bodies gathered against various exhibits. Conversations buzzed, suffixed by -isms, and alcohol. Bronzed faces, bold lipsticks — a Valentino pump here, a Margiela tabi there. It was a touching performance of society against the muted whites, soft lights, and street-facing clear glass walls.

The exhibition

- Repurposing

Across some pieces, I noticed the thematic repurposing of preloved materials. Satyam Mistry’s “how can I ask you to think with me?” used wooden structures to transform words such as “border” that are typically associated with exclusion into materials for building commonplace and safe space.

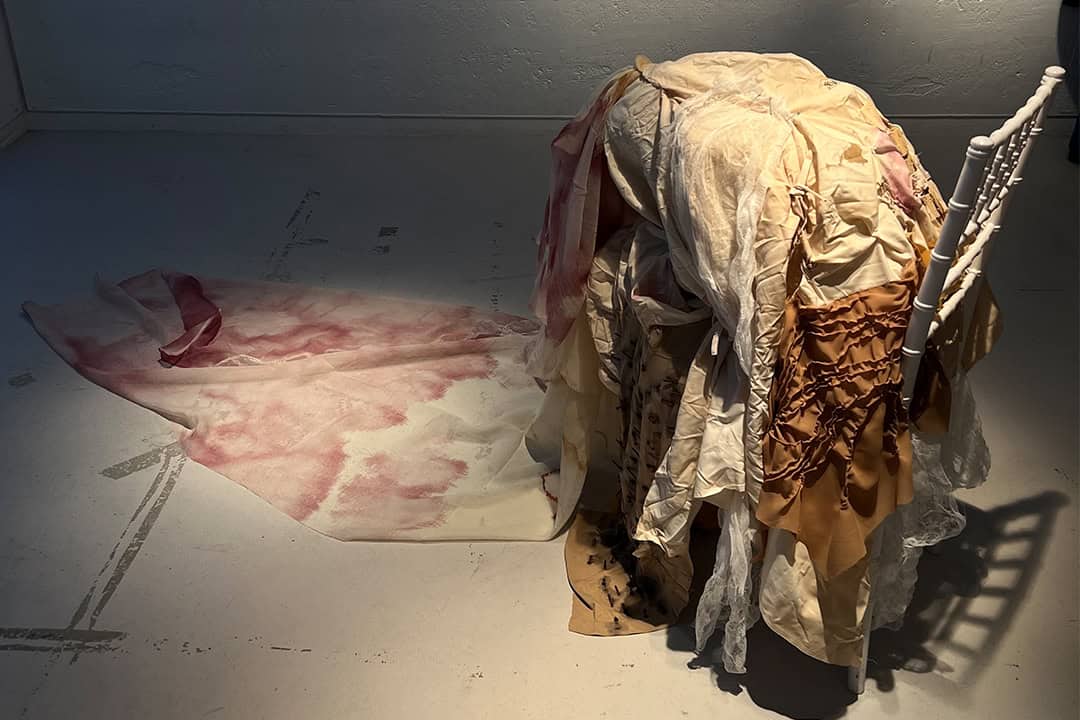

Janie Wang’s gothic cloth sculpture “Tie the Knot” and Lilian Zeng’s “faded intimacy, warmth disappeared” — both installments of mixed media and found objects — also repurposed preloved materials, albeit to a sadder effect.

Wang’s sculpture brought an unbearable scene to life: a feminine figure slumped over in a chair, appearing as if dead or unconscious, wearing a bridal-esque dress that altogether distorted the typical image of an idyllic marriage. This sculpture of iron nails, dismantled bras, bloody spilled wine, and other articles of domestic life evoked the horrors of maturity and adulthood, which impact not only women, but anybody who identifies with or aspires to embody femininity or womanhood, whether by choice or imposition.

Zeng repurposed her grandmother’s vintage wooden chair alongside a stitched tapestry of fabric from family clothes to brew deep nostalgia about the tattered, untidiness of any honest family portrait. It left me equally upset and appreciative of the raw, messy beauty of familial intimacy.

2. On language

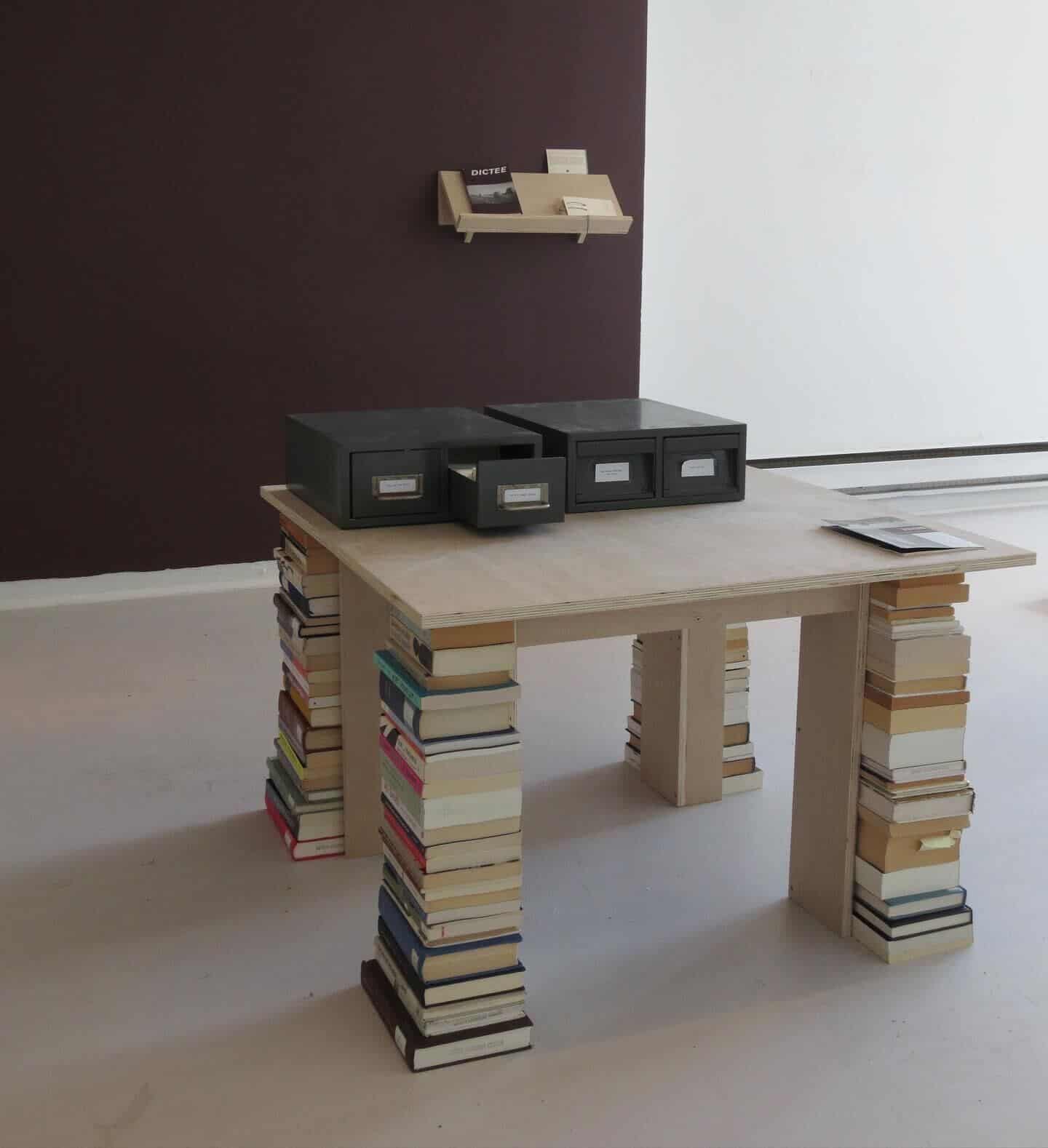

Another interesting sculpture was Auden Tura’s “La littérature au second degré.” This display comprised a selection of books upholding a “hypertextual poem,” a secondary text composed of bits and pieces of the texts that came before it — that upheld it. The sculpture altogether suggested reading and research as “alternative forms of writing” through the amalgamation and the recomposition of previous texts.

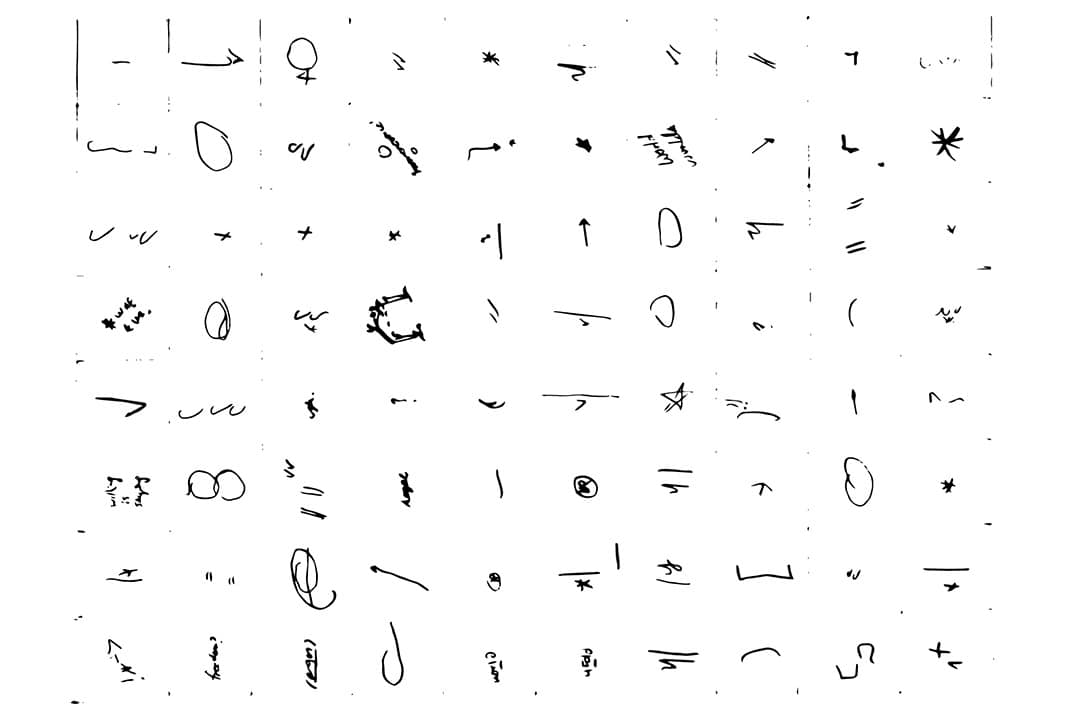

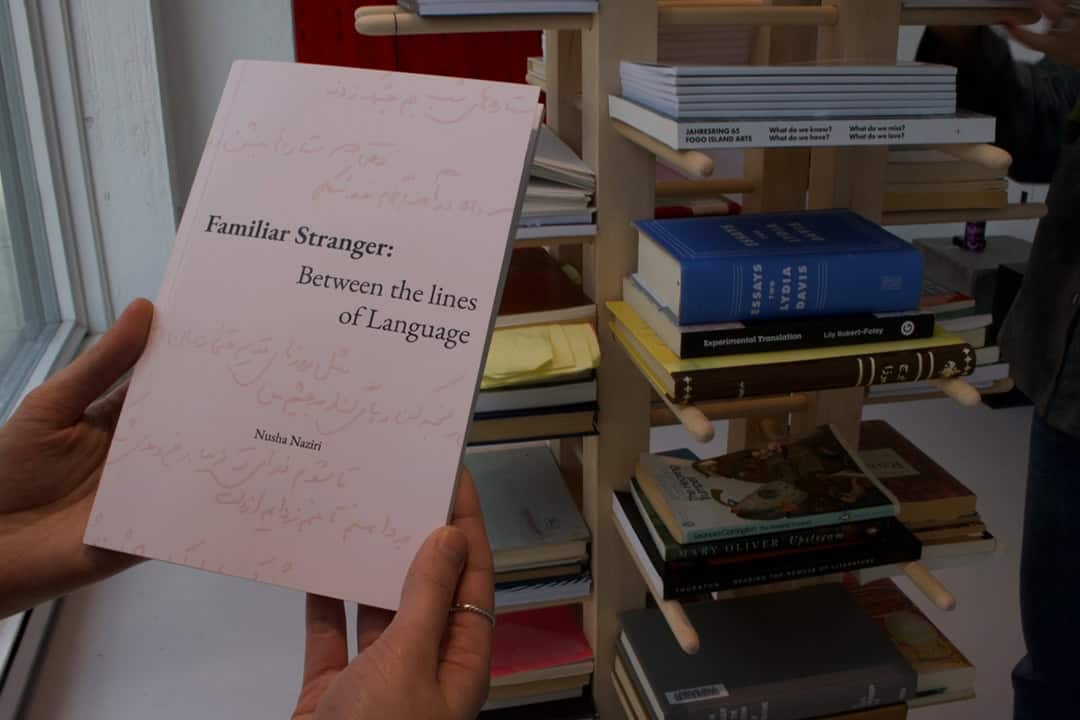

Meanwhile, Nusha Naziri’s “Familiar Stranger: Between the Lines of Language,” Rania Haider’s painting series “A Failure to Understand,” and Ella Spitzer-Stephan’s “Opera Aperta” all engaged deeper with language as a primary collective artwork.

Naziri explored alternative methods of translating, interpreting, and reading Farsi alongside her mother, while Haider’s acrylic paintings of broken Urdu text engaged with the loss of functional language and culture in postcolonial contexts. Additionally, Spitzer-Stephan considered annotation as a kind of mutation and simultaneous expansion of a text through the act of reading.

3. Digital media

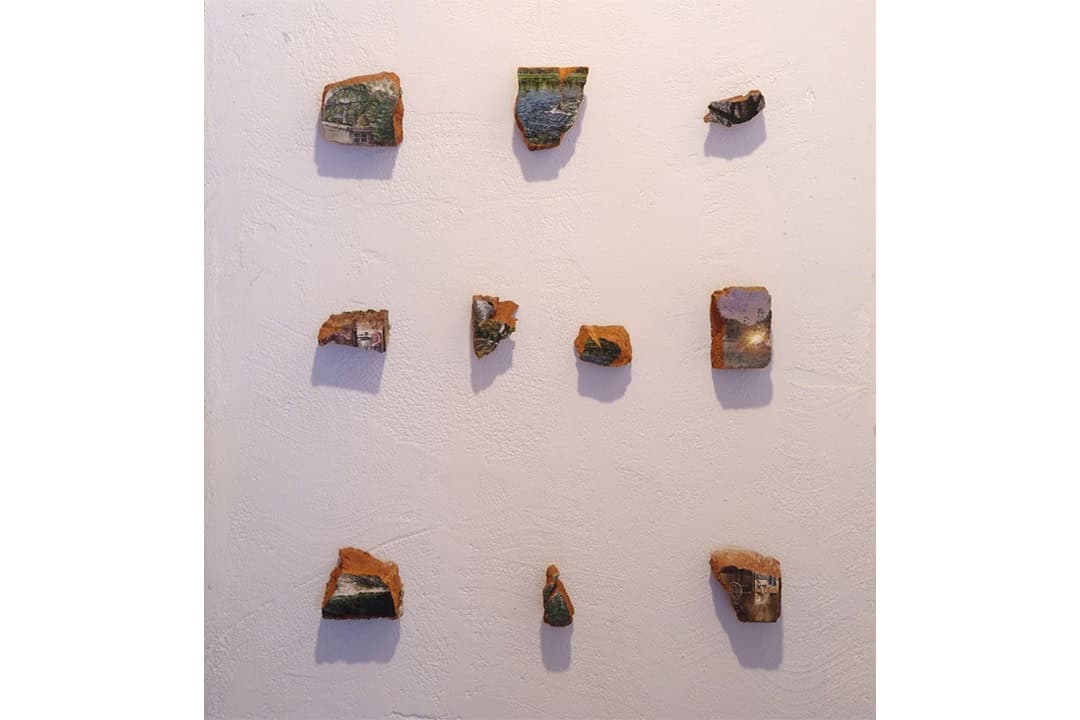

Olive Wei’s “What are art spaces without art?”, presented as digital files in flash drives, studied art spaces and curation as ways of generating community and producing knowledge by simply initiating social activity. Evan Bulloch’s multimedia installation, “bliss of the collector,” seamlessly combined a two-channel video loop with a melancholy series of acrylic paintings of family photos and stills from home videos on bricks from Bulloch’s childhood home. Bulloch successfully rendered a fragmented personal history, showing how one’s understanding of and relationship with the past is ever-shifting in response to the ever-changing present.

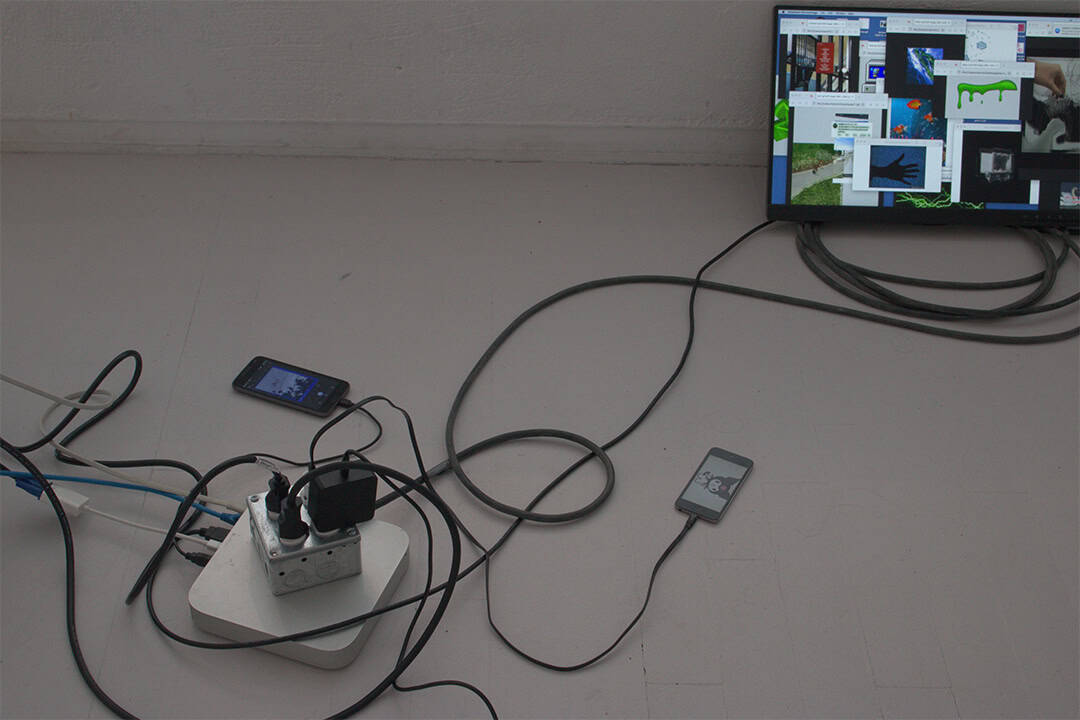

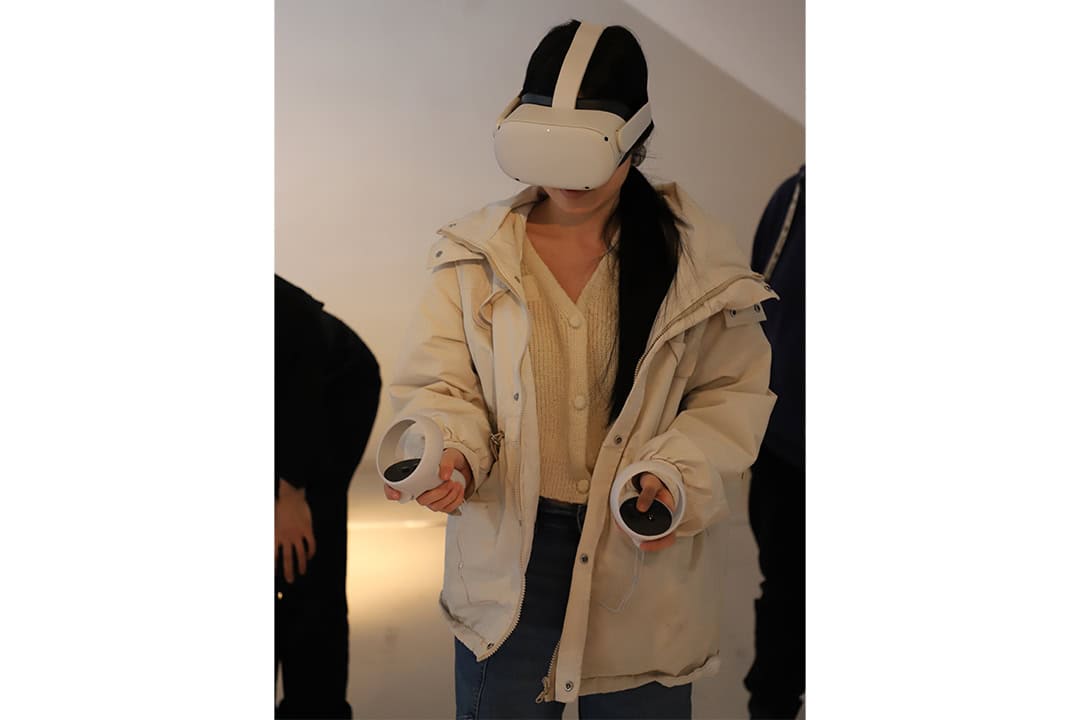

Nara Wrigglesworth’s “Post-gif” and Paris Chen’s “Colliding Canvases” immersed me in a landscape of looping GIFs and LCDs. While Wrigglesworth commented on digital decomposition and the pixelated human waste that collects from a chronically online culture, Chen’s interactive virtual reality experience emphasized the artistic merit of augmented reality.

4. Nature/human nature

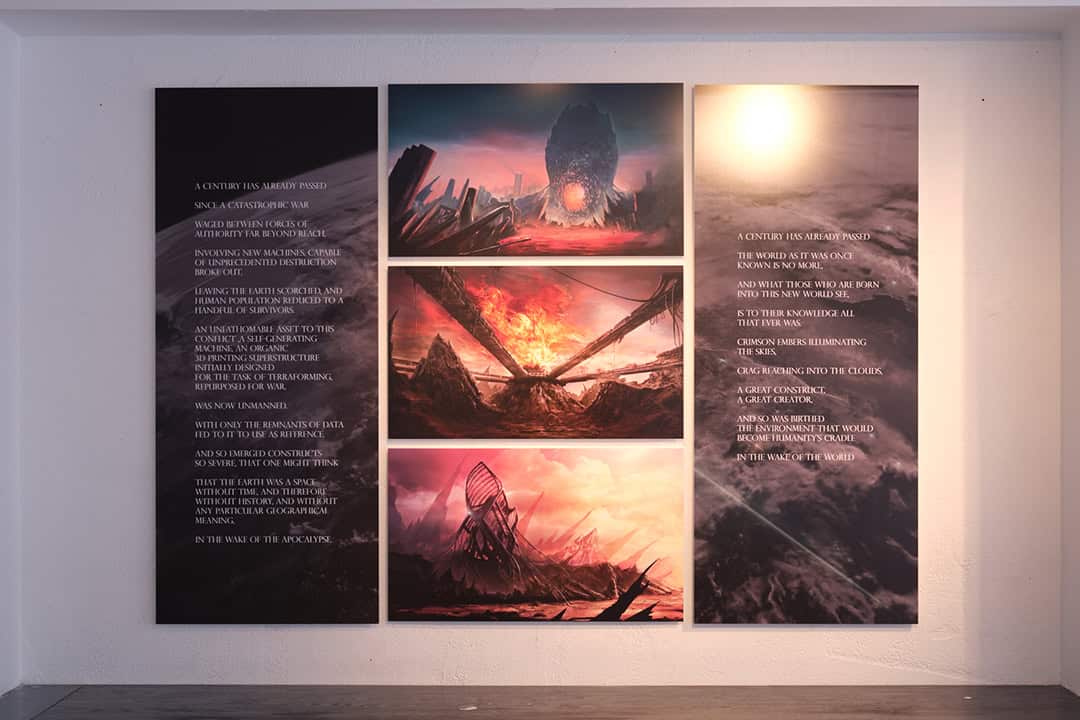

Maxen Wang’s digital portrait, “STRATA,” imagined a post-apocalyptic climate disaster created by “over-scaled human activities” of mass extraction and algorithm. As a dark mirror into the future, Wang depicted a monstrous landscape reminiscent of an injured animal — an injured Earth that grew teeth and claws and destroyed its assaulters.

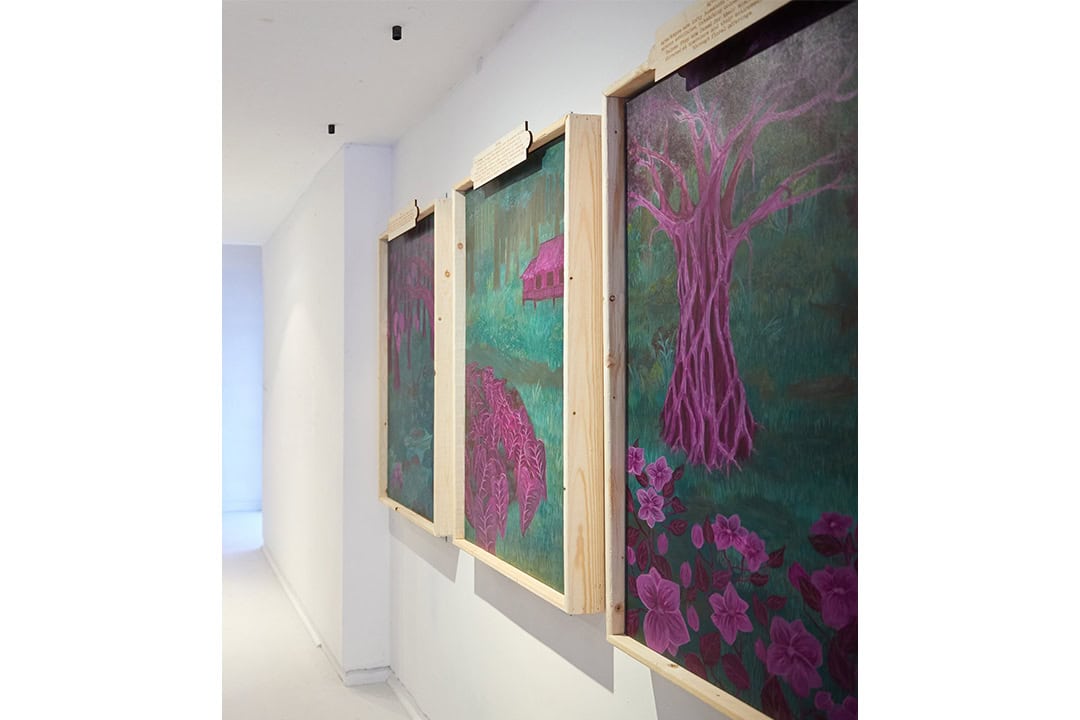

Similarly, Noemi Cabalbag delivered a monstrous natural world in “Navigating Reality Through Myth and Belief,” featuring three acrylic paintings inside wooden frames inspired by Filipino eco-mythologies, portraying mythic creatures that live within and as flora. By painting the mythic plants purple against the green trees, Cabalbag observed nature protecting itself through its own mysteries and our human fear of the unknown.

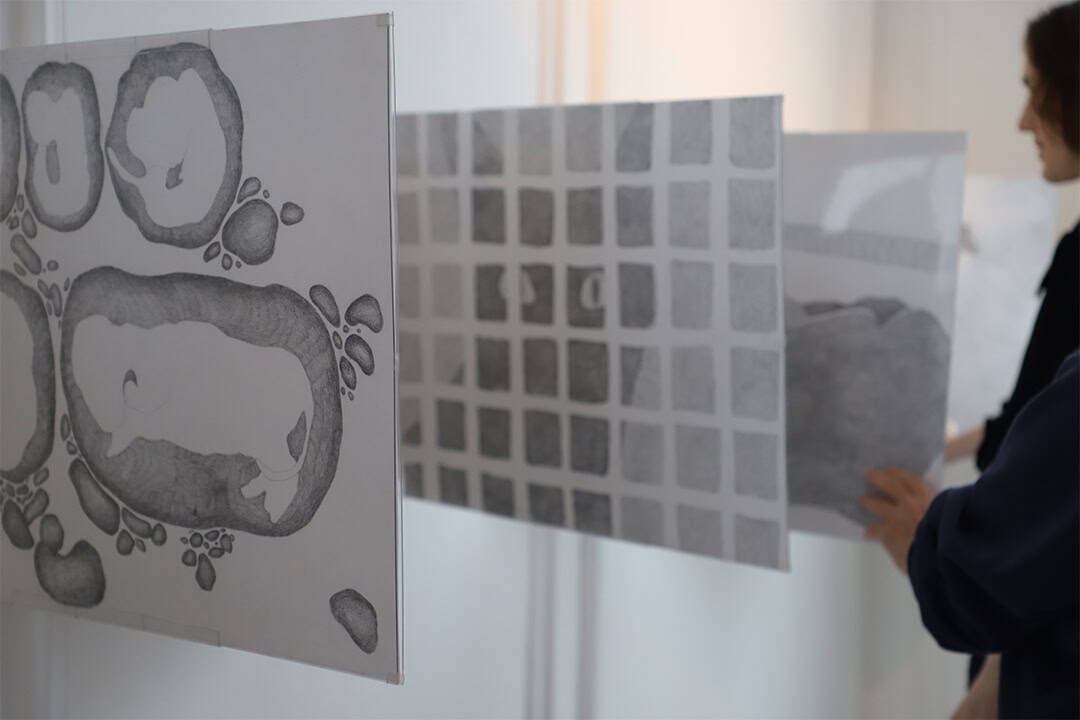

Some pieces stirred earnest sorrow in me for different reasons. Ashley Gu’s “The Unseen Red,” featured a printed, patterned Nüshu script against red fabric, nodding to patterns of solidarity between women suffering sexual violence and society’s collective complicity in this violence. Joy Li’s “Reflecting on Alex” portrayed the life, taming, and death of a once feral cat through a compilation of pencil drawings on paper.

Alex Lyu’s “Flow & Cover,” resembling a frozen avalanche of shredded paper on the side of a pulpy red mountain, commented on the nature of domination and authority, which flows from the top down, like lava during a volcanic eruption. Irene Song’s “Antidote” disarmed me with a multi-medium collage on Hanji paper, which posed questions to the audience, daring them to emotionally express their anxieties through interacting with water colors, color pencils, and oil pastels: using art as catharsis for healing.

Salma Ragheb’s “the constructed fabric, the consciously-induced collapse into classicality, the chaos of cosmic censorship,” was an interesting installment comprising collages, oil paint on wood and paper, and scholarly writings on quantum physics. Here, artistic expression blended with abstract science to reveal the incredible lyrical and poetic mould at the heart of quantum principles such as singularity, space, and time. It was the last installment that I looked at. It left me perturbed. Who knew the laws of physics held such seductive power?

The evening felt like a happy memory reflecting on itself and when it ended, I went home inspired by the achievements of my peers. Finally, I understood how noble it was to gather in the name of art.

Disclaimer: Salma Ragheb was the Science Editor in Volume 144 of The Varsity.

No comments to display.