Content warning: This article discusses death and grief.

On January 16, I was with my father when he died in Hospice care. Twelve hours later, I was on a flight back to Toronto. Twenty-four hours later, I found myself in class. In my dissociated daze, I was still, and in my immobility, I found that I could do nothing but observe my peers and their normalcy: the peers whose realities suddenly felt so distant from my own.

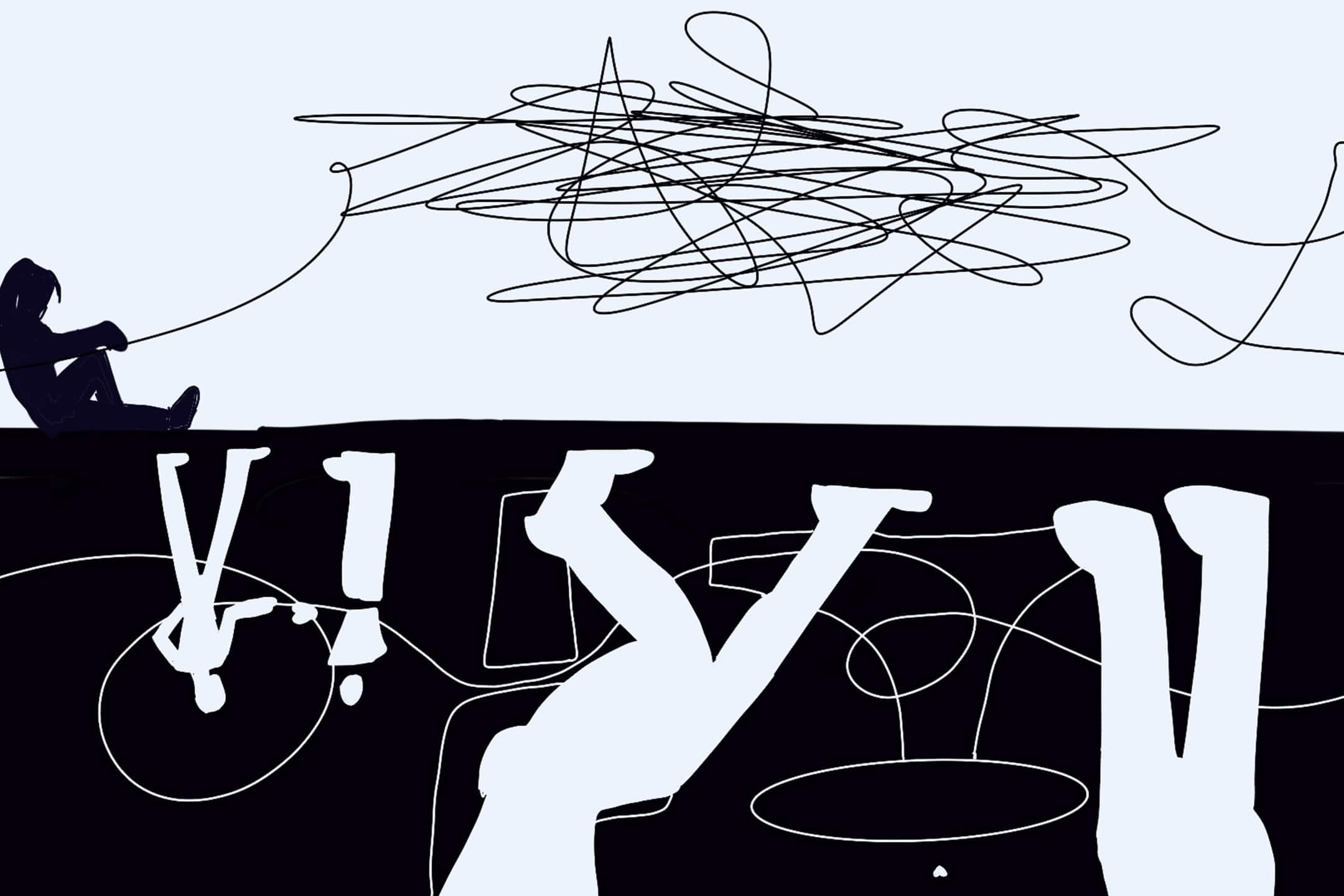

In most circumstances, it’s rare for me to keep my hands and feet still for very long. They twitch and twiddle unconsciously, like a secondary heartbeat keeping me grounded. It’s not necessarily a nervous tic but a perpetual ambience signalling that life is still within me.

The air of the lecture hall was stale like rotting wood and the sweat of a warm winter. There was a drone of quiet conversation that I couldn’t quite follow and a flood of white fluorescent lighting on desks, skin, and coats. It was in that one stuffy classroom when the events of the previous day finally registered and my body went still.

Early adulthood is a uniquely optimistic time. It is a time of energy and excitement: first apartment, first job, break-ups, make-ups — an ever-revolving door to people, places, and possibilities. The world is open, the horizon is expanding, and you are at the helm of its direction. These promises — and simultaneous pressures — are thoroughly ingrained in the way we conceptualize youth.

In the US, the legal drinking age is 21 and the age is prescribed as the standard of carefree invincibility. At 21, you can drink as much alcohol as your young and forgiving body will handle before blacking out. At 21, you should be unfettered at the precipice of life.

Generalizations like these exist in the cultural consciousness for a reason. They convey a broad truth about the shared experiences that construct youth in the abstract, and the degree to which you are aligned or misaligned from this shared construction has a real impact on your psychosocial wellbeing.

According to Oxford Languages, psychosociality is defined as “relating to the interrelation of social factors and individual thought and behaviour.” Being able to see yourself as a member of a socially constructed collective — like a collective group of young adults — offers security in understanding yourself and how you relate to others. This connection is foundational to a stable identity.

As much as we may find comfort in collectivity and social archetypes, our real lives are bound to deviate and therefore socially alienate us, but also bring us back together again in unexpected ways. I know this because I’ve seen it. I know this because I’ve lived it.

Misalignment, irony, and identity

Grieving, especially grieving a parent as a young adult, is an anachronism to youth. In this stage, you are still in a precarious moment of development in which parents are either the blueprint of what you are becoming — or what you are striving against — but usually not altogether absent from a young adult’s life. Additionally, there’s something almost perverse about being faced with the end of life at the beginning of your own.

This cruel irony puts the essence of your being and social identity in contention with the most visceral human stage: death. I found myself divided into two selves: youthfully beginning to establish myself, yet burdened by a pain that should only be known to those who are decades older and firmly rooted in their adult lives.

While my sisters and I sat by our dad in Hospice, I had a rosary in one hand and a bereavement pamphlet in the other. Apparently a social worker had come in and dispersed them, but my memory is too muddled to remember her being there.

I studied the glossy, neatly folded paper with an insatiable need to know what comes next for me as a surviving daughter, and I squeezed each plastic rosary bead between my fingers for the sheet-draped man in front of me. My father wouldn’t have wanted me to pray for him. He would have raised an eyebrow and said, “Pray for those who need it,” but I think at that moment, we both needed something to intercede for us.

Unfortunately for me, the information I was given did not equate to divine intervention. I very quickly found that the pamphlets were not written for me. For spouses and friends of course, but not the 20-something children of deceased parents. Not for an undergraduate student who has to fly abroad the very next day for a new semester.

In fact, someone should hire me to rewrite those stupid pamphlets. There was no warning in the pamphlet about how you’ll use your newly developed insomnia to doomscroll LinkedIn, or spontaneously cry in the grocery store check-out line, or feel nauseous every time you hear John Coltrane. It seemed as though even the information available to me — or lack thereof — was signalling to me that, “You’re not even supposed to be reading this. You’re in the wrong stage of life to be having this experience. You’re supposed to be in your prime. Why aren’t you in your prime?”

Importantly, the pamphlet neglected to tell me that with grief, I would age. Rapidly. Even more, that I would find everyone around me the same as I had left them. After a week of existential stress in Hospice with my dad, I came back to Toronto — still 21 in my body but with the eyes of someone closer to 41. I felt dysphoric between my mind, my body, and my abstract identity as a young adult. I was no longer myself as I had known her: a stranger in my own life.

Secondary grief

When you lose someone, you grieve twice. Of course, you grapple with the loss of the person, but you also grapple with the loss of who you were before the loss. You realize that you cannot recover your former self, and that your changed internal reality holds an equal permanence to your loved one’s changed external circumstance.

When I returned to Toronto, I came back hyper-aware that I’d seen an extremity of the human experience that some of my peers hadn’t — and hopefully wouldn’t — until they reached middle age. I saw my father die. With this prematurely lived experience, I realized that the structure of my life had been shaken loose from the social collective.

To put it lightly, my experience was a deeply isolating feeling of unrelatability. I felt that I could no longer share the wants, concerns, or hopes of my peers. Anxiety about GPAs and job prospects began to feel too trivial. While I sat at the back of the Innis Town Hall, sending emails to make funeral arrangements, I eavesdropped on my classmates sharing their fears about an upcoming midterm and I ached for their normalcy. I felt the wedge between our two realities so deeply. We sat in the same space but lived in separate worlds.

I grieved my father, but I also grieved my youth.

“God, I need to feel my age. We need to hit the club when I don’t feel so fucking awful,” was a line that my roommates heard from me quite often in the winter semester of 2024. Before his death, my father was too sick to travel and never had the chance to visit me in Toronto. But it’s a safe assumption that he would have supported my ‘trashy’ King Street clubbing endeavours.

I found that grieving involves a lot more tedious phone calls than anyone warns you about. If hell is real, I suspect it must be a lot like dealing with my father’s endless mess of financial affairs. Every day, I would get off the phone with some insurance company, estate lawyer, or accountant and rub my eyes, willing myself to have the energy of a 21-year-old.

One such phone call began with the woman on the other line sheepishly asking, “How old are you?” after hearing my voice. She was very earnest about it, but the irony of her question gave me a much-needed giggle. She wasn’t as amused as I was, but I suppose I’m like my father in that way: he had a sense of humour in bleak situations, especially about his own death.

At that moment there was a small solace, a youthful undercurrent, in laughing at that question and reviving a small part of him. Reviving also, a small part of myself.

It takes a village

Laughter brought temporary relief to my identity crisis, but my rapid aging was still manifesting in very physical ways. I was operating on only a sliver of energy, and all of it had to be spent working.

Every moment that I was able, I had to seize it and fulfill my commitments as a student, as a Cinema Studies Student Union executive, and as a video editor at The Varsity. I was desperate for social belonging, but I was at such a point of exhaustion that I could hardly even meet my most basic needs — never mind my more complicated, interpersonal needs.

I couldn’t spend time with my friends the way I used to. Although I had a desperate need to feel understood, I couldn’t give people my time or energy and I couldn’t participate in society’s carefree expectation of me as a 21-year-old. There was an extensive list of things that I couldn’t do or be in my time of grief, and it frightened me. I was alienated because I had shifted so violently into melancholy while the world around me, fuelled by the optimism of being 21, stayed the same.

There’s a saying that “it takes a village to raise a child,” but I found that it also takes a village to care for a grieving adult. It was my boyfriend and roommates who picked up the slack for my psychosocial wellbeing when I wasn’t able to. I felt so isolated because I couldn’t make them understand what I felt, but they took it upon themselves to embrace me — regardless of whether they could understand or not. They offered me empathy without a need to relate to my struggles.

It was my community who offered me the grace and understanding I could not give myself. There were many nights where I found dinner already made for me, and many days where my boyfriend would sit with me in the snow outside of the Old Vic in comforting and knowing silence. I did not have to be ‘myself’ in order to belong with them. My experiences did not have to be relatable for me to be understood. It was this overwhelming feeling of community acceptance that acted as a salve to my isolation. My fractured social identity post-grief slowly became less haunting and less all-consuming. I sat with it, I saw it, and I know that I still have a place in the world.

Epilogue (fingers crossed)

I can’t bring my dad back. I can’t undo what I endured. I can’t shake the knowledge of what death looks and feels like and because of this, I can’t fulfill the expectations of young adulthood as society has constructed it. But through the reassuring presence of my community, I’ve been able to reimagine my youth.

My youth is something not defined by inexperience, but something that still has room for optimism and possibility in spite of pain. Nowadays, a thought pops into my head constantly and it whispers to me, “There is still time.”

It’s been seven months since he passed away, and I grieve every day. But grief is no longer the epicentre of my being. This past summer, I spent my downtime processing the events of last winter and giving my tired soul much needed time to mend. My energy is still limited. I take things a little slower. But I am still Genevieve, still 21, still young, still at the precipice of my life, and still grounded by the community who continues to embrace me as I am.

I still walk into rooms of people with the knowledge that my experience with grief is not relatable to many, but that does not stop me from belonging. I belong despite the dissonant contradictions I have embodied. I belong, period.