Content warning: This article discusses the genocide of Indigenous peoples, and mentions violence and sexual assault in the residential school system.

On September 30, flags were lowered to half-mast across all three U of T campuses in recognition of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and Orange Shirt Day.

This year marked the 11th Orange Shirt Day, which was started by author and residential school survivor Phyllis Webstad of the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation. The day raises awareness of the intergenerational impacts of the residential school system and Canada’s need to seek reconciliation.

It also marked Canada’s fourth nationally recognized Day for Truth and Reconciliation, which was established as a statutory holiday by the federal government in 2021.

Hart House held its annual commemoration in the Great Hall and live-streamed for virtual viewers.

It featured keynote speaker Shirley Cheechoo — an actor, producer, artist, and chancellor of Brock University. Self-described as a “residential school warrior,” Cheechoo has infused her experiences in residential school and the challenges facing Indigenous communities into her art.

The residential school system

Starting in 1831, the Canadian government operated the residential school system in partnership with Catholic churches, aiming to convert Indigenous children to Christianity and assimilate them into Canadian society. For over 160 years, more than 140 residential schools operated in Canada, and the last residential school closed in 1996.

The residential schools aimed to erase Indigenous children’s identity by preventing them from speaking their languages or practicing their cultures. The children in the residential schools were subject to a lack of food, sexual and physical assault, forced labour, and inadequate sanitation.

In 2015, the National Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) found that the residential school system was a form of cultural genocide. It called for 94 actionable policy recommendations; however, as of writing, only 13 have been completed, while 18 have not yet been started. None of the calls to action related to Indigenous health, child welfare, or education have been fulfilled.

The TRC estimates 6,000 children to have died at residential schools. The former head of TRC estimated that more than 10,000 children had gone missing from residential schools. However, due to the churches’ and federal government’s poor record keeping, it’s difficult to put a number on how many children died in the residential school system.

Commemoration rundown

Around 300 tri-campus community members clad in orange shirts poured into The Great Hall, with more than 350 joining online to watch the commemoration.

Jay-Daniel Baghbanan — a student at the Faculty of Music and the faculty’s undergraduate association’s vice-president of student life — began with a land acknowledgment.

He recognized that the university has been operating on the traditional land of the Huron Wendat, the Seneca, and the Mississaugas of the Credit for hundreds of years.

Baghbanan also highlighted the violence that continues to affect Indigenous communities at the hands of Canadian law enforcement.

“It is an injustice to stay silent on the ongoing genocide of Indigenous cultures and peoples,” Baghbanan explained. “Since August 29 alone, nine First Nations people have died in contact with the RCMP or municipal forces in Canada.”

“[As] a highly ranked university, others look to us to set an example,” he said. “The work done by the Indigenous leaders here, [the] students who protest, and the faculty are immense, but we must all continue to hold our institution accountable.”

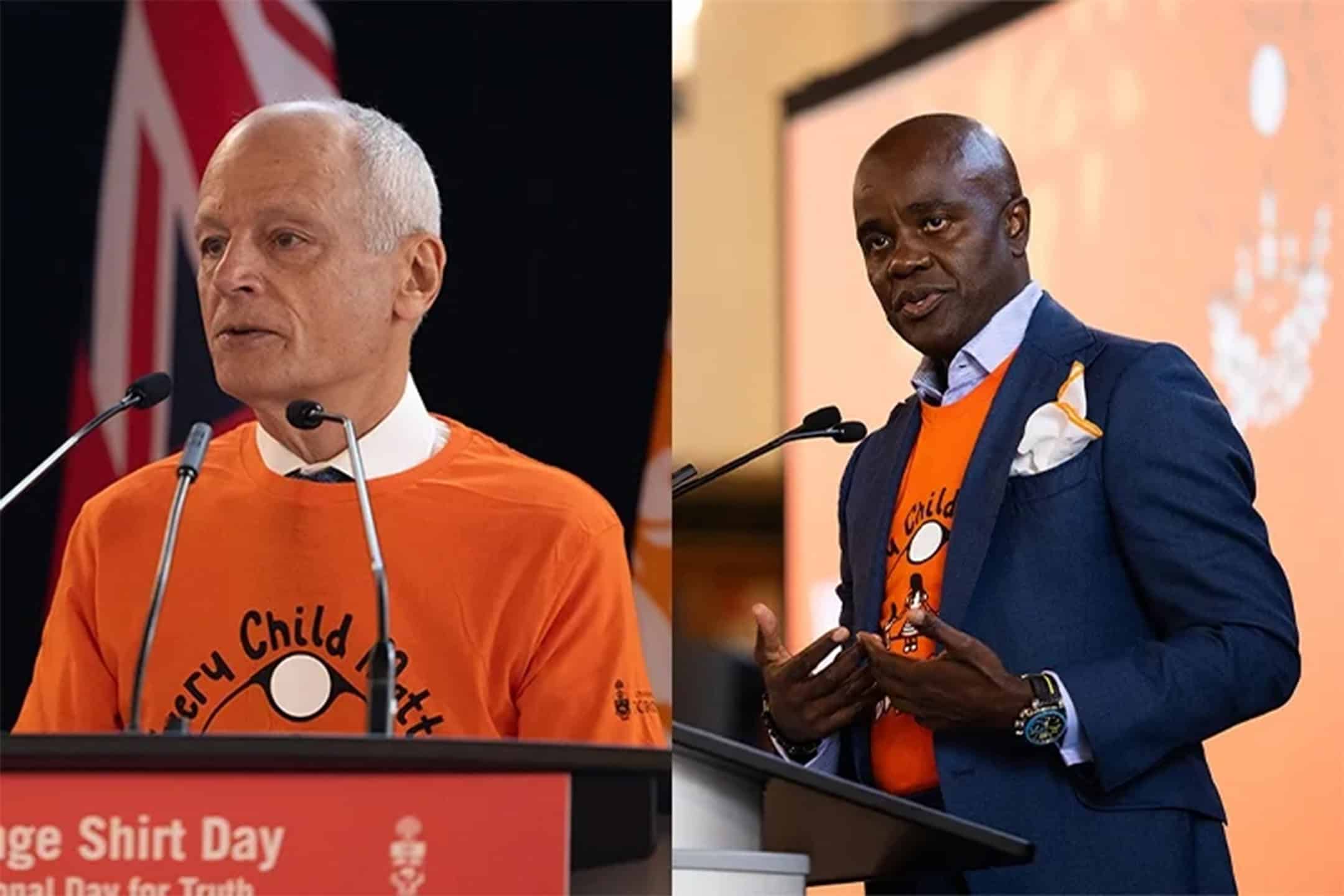

After Baghbanan’s remarks, U of T President Meric Gertler spoke. This year marks the first time Gertler attended U of T’s National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

“The University of Toronto community remains committed to advancing reconciliation across our three campuses and we are equally committed to working collaboratively with Indigenous members of the U of T community and the host First Nations,” he said.

COURTESY OF POLINA TEIF AND U OF T

Gertler shared that he met with the Chair of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, Ogimaakwe Claire Sault, and plans to work closely with the community to tackle housing and sanitation issues and to encourage Indigenous youth to attend U of T.

Gertler also noted the university’s initiative to cover tuition for students from nine First Nations communities, including those whose territories are adjacent to the land on which U of T is situated.

Acting Vice-President William Gough highlighted the importance of exposing the truth of U of T’s colonial history in his remarks.

“I come from a family with an almost 500-year settler history, with the arrival of my forebearers in 1639. So, I was thinking earlier today, this is personal,” he said. “But, this should be personal for every settler, regardless of how long or what pathway you came to this country.”

Many records related to U of T’s connection with residential schools are nonexistent. However, Wycliffe College, in particular, has a documented history of holding meetings aimed at recruiting students to work in residential schools.

Keynote speaker

As Brock University’s first Indigenous and first woman chancellor, Cheechoo began her remarks by expressing her gratitude to the school. A patron of Indigenous art, Cheechoo founded the Weengushk Film Institute — a centre for Indigenous youth to creatively share their stories with the world. She noted, “As an Aboriginal woman, I cannot stand aside and watch young people’s lives continue to fall through the cracks.”

Cheechoo remembers a time when children’s voices were always heard in her community. She explained, “The children ran the fields without the fear of being lost or taken by a stranger. Education in our community was the land, the elders, and parents; the whole community was our teachers.”

Cheechoo recounted her experience on the train to a residential school. “We watched as rivers of tears flowed down mothers’ faces,” she said. “I tried not to cry as the other children bang[ed] on the windows, trying to get out. My mother told me not to cry and to be brave and strong. For the first time, I felt empty, abandoned, and [as if] everything [was] clos[ing] in.”

Cheechoo said that, as a child, the abuse she endured in residential schools made her feel like a rabbit caught in a snare. “The more you resist, the tighter the wire tugs your throat,” she explained. “Now, all of a sudden, I have a voice.”

“I must embrace the weight that I carry of the past and stop being a victim of it,” she said. “I am not saying to forget but to let go and move forward.”

Next steps

All speakers at the commemoration agreed that there is more work to be done by all members of the university community.

Benji Jacobs — founder of Studio X, which centres on Indigenous art at UTM — shared that, “[U of T is] very behind in our progress in centring Indigenous voices… as students, we [feel] our institution hasn’t been hearing or listening to us” in an interview with The Varsity.

“I think we need to put a lot more effort and make ourselves accountable,” he said. “Truth and reconciliation is knowing and learning about the tragic legacy that precedes Canada and understanding the ongoing harm that affects Indigenous peoples.”

In an interview with The Varsity at the commemoration, Gertler noted that “our first responsibility is right here at home on our three campuses, making sure that [there] are welcoming spaces for Indigenous students, faculty and staff, and also working in partnership with the First Nations on whose lands we sit, as well as those nearby First Nations.”

If you or someone you know has been affected by the residential school system, you can call:

- Indian Residential School Crisis Line at 1-866-925-4419 (available 24 hours a day),

- Hope for Wellness Helpline at 1-855-242-3310,

- KUU-US Crisis Line at 250-723-4050,

- Talk4Healing Help Line at 1-855-554-4325.

No comments to display.