Content warning: This article discusses misogyny, sexual violence, substance use, and eating disorders.

My mother loves to travel. Or, more accurately, she loves to fantasize about it. Imagining herself as a tourist taking on the glamourous streets of Paris or the chaotic medinas of Marrakesh. Sooner or later, however, she is forced to abandon that elusive realm of possibility for the realities of wifehood and motherhood.

Countless times I’ve sat at our oakwood dinner table, lazily stirring the bowl of chicken noodle soup my mother made me when she asks how the food is. Does it need more salt? Is that spoon the right size for you?

However, what she really wants to ask is: Am I a good enough mother? Have my sacrifices for you been worth it?

As a South Asian woman, my mother was raised to believe the emotional and mental burdens she takes on are translations of her love and worthiness as a mother. But I often wonder what about her self is independent of this? Who does her emotional caretaking?

I sometimes find myself taking after her accommodating personality. In my friendships with some men, I find myself hyper-analyzing what I said and how I acted, while retrospectively contemplating the social situation from their perspective. I try — sometimes foolishly — to discern their feelings, intentions, and desires, often more than they themselves are expected to.

I recognize that as social creatures, it will always be our destiny to find the greatest comfort and meaning in relationships with others. However, I don’t believe women must attain this at the expense of self-minimization, of self-sacrifice, all for a patriarchal sense of the greater good or compliance with societal expectations of women, mothers, and daughters.

The righteousness of sacrifice

Sacrificing one’s menial comforts, or even something more significant, for a cause greater than oneself has long been a beacon of nobility in religious and political realms. In fact, the ritual and concept of sacrifice date back to many ancient civilizations that practiced polytheistic religions and, subsequently, the Old Testament, which laid the foundation for Christian ideals of sacrifice. Material and human sacrifices — specifically practiced by Mesoamerican societies before Christopher Columbus’ arrival — were central to establishing, strengthening, and restoring divine alignment with deities, thereby achieving a state of salvation and spiritual cleanliness.

Revolutions that would go on to alter the course of history have often been galvanized by instances of martyrdom. Take, for example, the execution of King Louis XVI during the French revolution. For the revolutionaries, his guillotining was sanctioned as the gateway to a new democracy, while for supporters of the monarchy he was a Christian martyr whose spirit would return to save France from the sins of its revolutionaries.

To surrender and sacrifice then, is to lay oneself bare, spiritually, and emotionally, at the dawn of a cause greater than ourselves. Even divorced from the religious and political, sacrifice is an intensely personal aspiration that reveals our true priorities and strength, helping us build a clearer portrait of who we are as individuals.

Reconditioning sacrifice

But this romanticized notion of sacrifice is far removed from the realities faced by women and young girls as they navigate work, romance, wifehood, motherhood, aging, or most importantly, selfhood.

Interpersonal as well as societal relationships between men and women function as a political institution designed to ensure men’s physical, economic, and emotional access to women. Similarly, patriarchy operates to institutionally socialize women towards a sacrificial identity to ensure the ‘greater good’ in relationships, families, workplaces, and even entire nations.

Women’s dual role in the domestic and public spheres highlights the normalization of women’s unpaid labour in the household alongside their contributions to the public or professional spheres.

In a 2008 study in The International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, several professional women in India spoke about their perceptions of their role in society and relationships. One woman said, “I gave up a professional career in a multinational company, which I planned for myself, but this was a voluntary decision when I got married and had children.” Another woman with a masters degree claimed that because her husband is busy as a lawyer, he “is totally dependent on” her to stay home and take care of him.

Outside of paid work, women do two and a half times more unpaid care and domestic labour. Unpaid care work includes not only the physical labour of running a household but also the emotional investment in raising and caring for children and other dependents, such as the elderly or in-laws. On top of this, women are expected to make it all look effortless. The household work that women do — whether they’re raising children or pursuing a career — often goes unappreciated because it is a gender expectation and does not create material value.

A patriarchal society redefines sacrifice as tied to women’s worthiness in this world, whether that be worthiness for her husband, her children, or society at large. Without this necessary reconditioning, the patriarchy would not survive as it thrives on the unacknowledged sacrifices of women.

The gendered burden of sacrifice: perceptions and consequences

Even though patriarchal standards harm men too, sacrifice is a gendered conversation because the motivations behind and consequences of sacrifices differ between men and women. The patriarchy associates femininity with vulnerability, dependency, and complacency, and defines masculinity through power, status, and strength — and individuals such as low-income men or members of the 2SLGBTQ+ community who do not conform are often outcasted as ‘effeminate.’

Gendered dynamics of sacrifice often play out in intimate relationships between men and women, where the sacrificial capacities of each partner contribute to the stability of the relationship. However, in a healthy relationship, a balanced level of commitment, where both partners should be willing to make sacrifices is important. Yet women and men inhabit different social roles mandated by the patriarchy, which creates sacrificial asymmetry.

According to a 2020 study in Current Issues in Personality Psychology, although both partners sacrifice for the relationship, men perform sacrifices tied to their lifestyle and sense of obligation such as socializing more with their partners than their male friends, while women make sacrifices associated with their socialized roles as nurturers and caregivers — often sacrificing their own emotional and psychological wellbeing for that of the family or relationship.

Some may argue that the masculine and feminine capacities for sacrifice complement each other to mutually stabilize a family or relationship. However, this perspective overlooks the importance of achieving harmony in a way where both partners contribute equally to emotional and material sacrifices.

When one party in a relationship feels that they’ve given up or compromised more of themselves — such as women who do all the emotional work in a relationship, or who have sacrificed their careers for their husbands’ benefit — the imbalance of sacrifice can often breed discontent. Therefore, it is unsurprising and perhaps warranted that the asymmetry inherent in the social roles of men and women can create a sense of injustice in women.

The societally ordained capacity for certain types of sacrifice between men and women serves as an arbiter for both masculinity and femininity. Both men and women make sacrifices to maintain a positive impression of their masculinity or femininity among their interpersonal relationships. The crucial difference is that women make sacrifices for the men in their lives, while men, too, make these sacrifices for the approval of other men. If women are not to be sidelined, they’re forced to impose the patriarchal standards on other women, just to have a leg up over some women — but never over men.

The patriarchal panopticon

While both men and women sacrifice, women often face tangible consequences when they fail to make suitable sacrifices — oftentimes to accommodate the egos of men.

For example, in many South Asian households, women who do not follow a prescribed timeline of marriage and motherhood may experience both humiliation from their families and internalized perceived incompetence as women. In certain cases, their families may even cut ties with them financially.

The panopticon, a term coined by philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham, describes an architectural design in which individuals cannot know when or if they are being watched by an authority figure, and are thus compelled to self-regulate to avoid punishment from said figure. The patriarchal architecture has a similar design, where women and other gender minorities behave in ways that cater to the gaze of the patriarchy in order to pacify or please it. In doing so, sacrifices become inevitable.

Sacrifice is survival: Bangladesh’s Kandapara village

Women’s sacrifice is systemic and normalized in Bangladesh’s Kandapara brothel village.

On a dewy evening, a young woman navigating the labyrinthine and reckless streets of Kandapara, waits in line at a local makeshift pharmacy. She doesn’t have a prescription, nor does she know the consequences of the drug she’s about to request from the “pharmacy vendor.” Wide-eyed and jittery, the woman hurries back to her pimp with the medication in hand, avoiding the gazes of men who will soon become her clients as the night nears.

Kandapara, Bangladesh’s oldest and largest legalized brothel, is a slum where girls and women are not only prostituted but also live in, often without formal access to education. Though sex work was legalized in Bangladesh in 2000, sex trafficking and exploitation were not, and those are the primary ways young girls enter Bangladesh’s Kandapara brothel village. Through watching several documentaries and reading interviews, I learnt that these young women and girls are sold, bribed, or tricked into a world where sacrifice to such brutal lengths is normalized and systemic.

Girls without formal education and who are from low socioeconomic backgrounds are typical victims of sex trafficking, brought to Kandapara by pimps to serve clients who flock from the country’s dense urban centres to ‘cool off.’ There are no reports on exactly how many girls are being sold into prostitution, nor how many clients they can expect to meet daily. Kandapara’s residents earn meagre wages while enduring terrible physical, emotional, and mental conditions. Their health is further endangered as the government rarely enforces safety measures.

Women in Kandapara regularly take Oradexon, a steroid meant for fattening cattle. They are told by their pimps that Oradexon will make them plump and curvy, and therefore more appealing to the men that roam the streets of Kandapara. Oradexon is highly addictive and can lead to liver and kidney failure, and UK charity ActionAid estimates that 90 per cent of the 200,000 women in Kandapara are addicted to it. Yet, the women continue to take the drug, forced by their conditions to sacrifice their bodies and dignity.

Accidental pregnancies are common, and the daughters of Kandapara’s working women are expected to transition into their mother’s job without question before the age of fifteen. As girls, they sacrifice the sanctity of childhood in favour of the patriarchal plan. In a deeply heteronormative society like Bangladesh, the inevitability of this cycle — along with the fact that women are forced to conflate submission and subordination with survival — underscores how selfhood is contingent upon these sacrifices.

This martyrdom is reflected in various trends, all over the world, such as the popularity of cosmetic surgery, and begs the question: for whom are we performing under this panopticons gaze?

Beauty and martyrdom

While the body dysmorphia epidemic certainly affects men, women constitute the majority of sufferers at 60 per cent globally. Confronted with runway models to porn stars, women face dualistic beauty ideals: large breasts, or small ones? Tiny waists, or thick thighs? Consequently, girls and women resort to makeup, surgery, and even drugs to try and reach a semblance of this unattainable standard of perfection.

The realities of sacrificial appeasement thus quickly materialize in the multi-billion dollar beauty industry. Girls and women are compelled to compromise and, indeed, sacrifice their psychological and physical wellbeing to compensate for ridiculous cultural standards. Just look at the ‘Sephora Kids’ — 10-year-old girls spending hundreds of dollars on harmful skin products — to the climbing numbers of people, including teenagers, getting plastic surgery. In 2020, 92 per cent of all procedures globally were for women.

However, sacrifice itself is not the enemy; rather, it is the unequal burden on women to sacrifice and conform to patriarchal social roles that is problematic. It is not the desire to be beautiful that is of concern, but the obligation to be, specifically for the appetite of men.

The parts of ourselves we choose to sacrifice for a ‘greater good’ we deem worthy reveal much about our identities and the world we live in. But to question, resist, and prioritize one’s needs and self-vision in the face of sacrificial demands often invites accusations of selfishness, immorality, and being unfeminine.

In many South Asian and other deeply patriarchal societies, for instance, the pinnacle of womanhood is often defined by the roles of mother, ‘good wife,’ and a palatable daughter-in-law. When a woman becomes a mother, she must juggle emotional, financial, and physical sacrifices. In contrast, men, who are highly respected in Indian society, are primarily expected to fulfill the role of a provider, often materially, to be celebrated. Meanwhile, the mothers and wives tend to operate in the background of their husbands’ lives.

Invisibility and sacrifice: self-erasure in relationships

The work that women do — whether it involves raising children, pursuing a career, or sacrificing their own ambitions for others — often goes unappreciated because it is expected without their contestation. For many women, sacrifice becomes a form of emotional and cognitive labour rooted in their relationships with men. Social expectations impose an unequal burden on women, demanding that they not only manage their own emotional and cognitive states, but also do the ‘invisible’ work of catering to and appeasing the emotional states of others.

I needn’t look further than my mother to understand why so much of her emotional and cognitive energy is directed toward her interpersonal dynamics with my father, as she has always been the emotional caretaker in her relationship with him. Whenever their arguments escalated, it would often end with my father barging into his room, slamming the door — the sound reverberating through the house. It was always my mother’s job to explain to us what had happened — but why?

My mother is happy to fulfill her duties as the emotional caretaker of the family, while also being a professional. However, I’ve come to understand that her willing obedience is a form of self-inflicted invisibility — a form of self-erasure rooted in the expectation to cater to the patriarchal gaze of who she is supposed to be.

Oftentimes, oppression isn’t grand. It can be woven into the fabrics of everyday life, manifesting in the trivial duties we assume as a consequence of a patriarchal society, under the belief that these roles we play will bring us happiness.

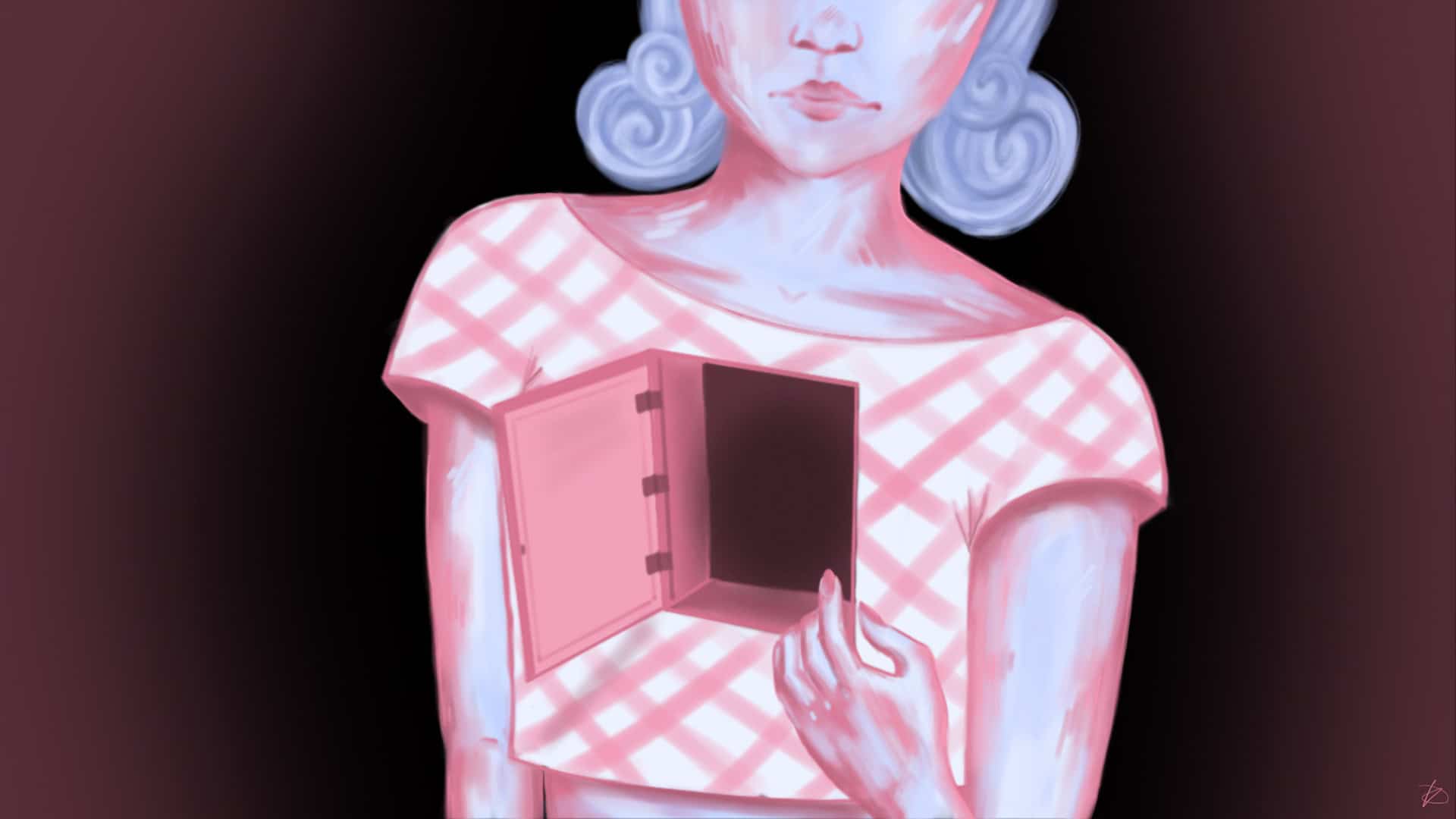

Self-erasure is the key demand of the patriarchal project on women. Construing the sacrificial identity, even to brutal lengths, as a definer of a woman’s worth as a mother, professional, and human being tells women that they must fully sacrifice their vision of who they want to be in order to be worthy of their femininity — to earn it, even.

To see one’s self entirely and independently of the sacrificial roles is to exercise a rebellious facet of self-love. Indeed, this capacity to recognize ourselves as whole — acknowledging our desires, feelings, pains, and triumphs as fully realized and not contingent upon another’s definition — is true self-love. It is this awareness that can halt the cycle of generational harm.

Women have always been the backbones of families, communities, and economies. They have been and continue to be the soul of revolutions that have shaken the world. It is a woman’s trust in her true self, along with the power and expression that comes with it, that forms the lifeblood of all that is sacred in this world.

But in parts of the world where this sacrificial identity is deeply ingrained and goes uncontested, how can we expect women to build strong identities independent of the patriarchal panopticon? As a student, typing this out behind a screen and continents apart from the women in Kandapara, I can only address so much of their realities and the culture of sacrifice and patriarchy upholding it.

But I think it’s important to note that the same parasitic patriarchy that enslaves reluctant sex workers in Bangladesh is the same one that affects women and men everywhere, regardless of geographical boundaries. As a woman, my personal resistance against any form of toxicity imposed on me will only manage to disrupt a small corner of patriarchy; but this does not demotivate me. We might not be able to undo centuries of systemic oppression by our individual defiance, but neither are we free to abandon trying altogether.