This is the third part in a three-part investigation by The Varsity into international students’ financial struggles at U of T.

“I really didn’t think about the tuition too much until the pandemic year,” says Luise Hellwig, a fourth-year international student from Germany. “But then the pandemic hit, and I was not getting what I was signing up for.”

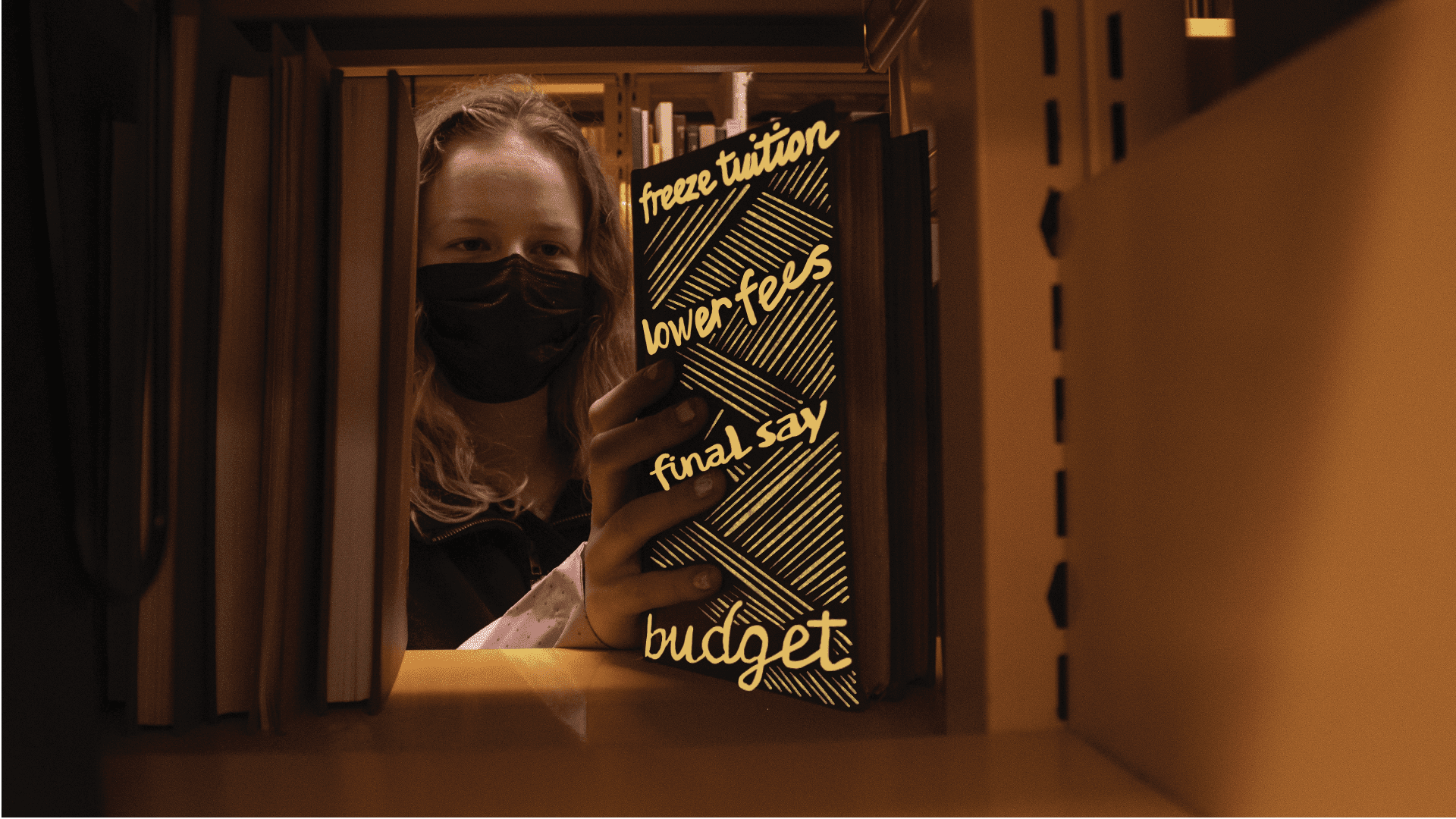

She did not do well with online learning, and was very frustrated. “And then, of course, not only did [U of T] not freeze or lower tuition because of the lower quality of education, they also increased it by five per cent in that year,” she says. For Hellwig, that was the last straw — she joined a newly formed international student group at U of T, the ISAN. The ISAN has been representing undergraduate international students at the FAS since summer 2020.

During the pandemic, it advocated for the significant reduction of international tuition and increased transparency on how international tuition is used and allocated. It also started talking to senior members of administration. But the ISAN is far from the first organization to advocate for international tuition fee reductions at U of T.

Calls to lower international tuition fees have existed ever since the idea of differential fees was introduced in 1976. At the time, the Ontario Federation of Students created a province-wide petition to oppose the tuition hike. The Academic Affairs committee at U of T rejected the university’s proposal to increase international tuition by 2.5 times “as a matter of principle.” Simcoe Hall burst into applause when the committee made this decision. One month later, President Evans led a delegation from U of T to negotiate the policy with Minister of Colleges and Universities Harry Parrott.

International students themselves mobilized to oppose the fees. The Varsity reported on Chinese students’ associations from universities across Ontario holding conferences and releasing statements denouncing the 1976 increases.

CAROLINE BELLAMY/THE VARSITY

Thirty-five years later, in 2011, Mary Githumbi came to U of T. Githumbi, who was an international student from Kenya at the time, was attracted by U of T’s wide portfolio of education and research opportunities. However, she was disillusioned by the lack of support for international students when she got here. “We felt like cash cows coming in,” Githumbi says in an interview with The Varsity.

Githumbi decided that international students needed a representative body that would advocate for their interests. So, in 2014, she co-founded the International Students Association (iNSA) with Marine Lefebvre, an international student from France.

Together, they set their sights on getting international students on the Governing Council, which has final say on tuition fees and budget allocations. The University of Toronto Act of 1971 — a provincial legislation that regulates the Governing Council — had barred non-citizens from serving on the Council. This meant that international students had no say on matters relating to their tuition.

So, executives from the iNSA talked to the University of Toronto Students’ Union (UTSU) and constitutional lawyers at the U of T Faculty of Law. They published articles in The Varsity, approached students during lunch breaks, and held social events like pub crawls and Thanksgiving dinners to forge connection and understanding. Githumbi said they even filmed Yeliz Beygo, an international student with Swiss and Turkish citizenship, as she brought her nomination application and passport to Simcoe Hall, where the officer rejected her application.

Finally, in July 2015, the provincial government amended the Act, allowing international students to serve on the Governing Council for the first time.

While the structure of the Governing Council is still problematic, according to multiple student leaders — only eight out of its 50 seats are reserved for students, which means most of the council is controlled by non-students — this was a significant step in securing international students’ political rights and representation at U of T. But today, campaigns to lower international tuition continue to face structural barriers that are more far-reaching.

Inaction from the U of T administration

“There’s nothing we can do.”

That’s what senior administrators often tell the ISAN, according to Hellwig.

The ISAN has met with the Office of the Vice-Provost, Students multiple times to discuss international tuition — but to no avail. Hellwig describes these meetings as “fruitless.” Multiple interest groups were often present at these one-hour meetings, so, Hellwig says, the ISAN would sometimes only have 10 to 15 minutes to discuss international students’ financial struggles and offer potential solutions.

Apart from the ISAN, the UTSU and the University of Toronto Mississauga Students’ Union (UTMSU) have lobbied senior administrators to lower or freeze tuition fees. But administrators dismissed these demands and explained that the university required that funding, citing necessary investments in digital infrastructures and a lack of government grants. Instead of lowering tuition, they pointed students toward financial aid.

From then on, both student unions have lobbied the province to increase operating grants to U of T. The 2020–2021 UTSU submitted recommendations to the province ahead of the 2021 Ontario Budget, but these efforts saw limited success. “The government does not seem interested in reversing the trend of declining operating funding and increasing tuition fees,” wrote Tyler Riches, the 2020–2021 UTSU Vice-President Public and University Affairs, in an email to The Varsity.

When asked what kind of support the UTSU received from U of T administrators in these lobby efforts to the province, Riches wrote, “To be frank, not much.”

The UTMSU has also urged senior administrators to join student unions in lobbying the province to increase government grants to the university. However, Mitra Yakubi, the current president of the UTMSU, writes that university administrators never responded to their calls.

“We have not seen much willingness from the University of Toronto administration to work with us to find tangible solutions,” wrote the UTSU in a 2021 statement.

On March 31, U of T’s next operating budget is set to go before the Governing Council. It proposes to increase international tuition by another two per cent on average for the 2022–2023 academic year.

How much should international students pay?

Aliya once asked a university employee why international students pay so much. She was told that it’s because international students don’t pay taxes in Canada.

However, Aliya was not convinced. She says that if a business owner charged $5 to locals for a bag of milk, and $50 to non-citizens, then that business would be effectively shut down. But educational institutions routinely do that, which, she said, is “even worse.”

In addition, international students do pay taxes in Canada. They pay GST/HST for most goods and services they buy on Canadian soil, and those who are employed pay income taxes like any other local.

In 2019, U of T President Meric Gertler said that international tuition at U of T is priced to cover “[the] full costs associated with educating those students.” However, international and domestic students attend the same classes, tutorials, and labs, and have the same professors. As one Varsity op-ed pointed out, U of T does not disclose what these “full costs” are.

The same article cited Gertler saying that international tuition covers the costs of services like “special counselling [and the] Centre for International Experience.” However, these services fall under incidental fees — not tuition.

Ultimately, Aliya doesn’t call for equal tuition with domestic students, because she understands that countries give their own citizens more privileges. Still, she asserts that there needs to be a “certain degree” of regulation on how much the university charges international students.

Portelli comes to the same conclusion. “If someone goes to study in another country, it is, I would say, fair for that country to charge that student something extra… The question is proportionality.” He says that there must be a balance between charging international students higher fees and still making education accessible for them.

But what happened to PhD international students at U of T in 2018 was even more radical than a simple reduction of tuition. In January of that year, U of T reduced the tuition fees of the majority of PhD international students to match their domestic counterparts.

“We strive to remove any barriers, financial or otherwise, that graduate students might face as they look to attend our university,” Joshua Barker, dean of the School of Graduate Studies and vice-provost of graduate research and education, said at the time of the announcement.

In compliance with the second Strategic Mandate Agreement between the university and the province, the government significantly increased operating grants for international doctoral student enrolment. “[One] requirement of operating grant funding is that students are charged domestic fees,” a U of T spokesperson wrote. However, the government only limited this policy to international doctoral enrolment, which is why only PhD international tuition fees were reduced.

Ultimately, Portelli urges all of us — particularly those who work in universities — to remember their purpose. “The major purpose of the university is not to make money; the major purpose of the university is to enhance and promote the education of students, both local and international,” he says.

He reminds us that the word ‘university’ comes from the Latin word ‘universitas’ — universal — which means that a university needs a diversity of cultures, ways of thinking, and ways of being for its own educational fulfillment. “Having international students is important for the very nature of a university,” he adds.

Is all of this worth it?

Shoena and I had just finished our interview. I turned the recording off, and we proceeded to talk about U of T’s work-study program. I had just finished explaining the 20-hour working limit for international students when Shoena said, “I just have to ask you — is studying at U of T worth it?”

This is a question that many international students continue to grapple with.

I was silent for a few seconds, and then sighed. I didn’t know what to say. As an international student myself, I could not come up with an easy answer.

In many ways, I am happy that I’m here in Toronto. Learning from kind and brilliant professors at U of T has changed my life. By working in different jobs and roles throughout the university, I’ve discovered surprising things about myself and what I’m capable of.

However, I am not happy with the circumstances that brought me here — the fact that colonization and debt have weakened the Philippines’ already weak education system; the fact that I have to travel over 13,200 kilometres away from my home, friends, and family just to get a good education; and the fact that I have to feel like a parasite on my parents’ bank account for all of this to happen.

I am not happy with the precarity and insecurity that’s central to my temporary residency status here in Canada. An aunt warned me to never attend demonstrations of any kind, because she fears that I could be easily deported. When my roommates and I were looking for housing, three realtors told us that international students were required to pay 12 months’ rent up front — when this is in fact illegal.

Whenever I sit in a classroom with my domestic peers, I think to myself, “I pay 10 times more to be in the same room as them.”

U of T, Ontario, and Canada more broadly all now rely on international students to subsidize postsecondary education. Yet, many still deride international students as a strain on the country’s resources, and international students are often left without support, protection, representation, and full rights.

“Don’t we deserve better than this?” Aliya asked.

Alongside advocacy groups and student unions, international students themselves have long been fighting for tuition equity and equal rights; they continue to do so today. Now, with increased collaboration between the province and the university, it is possible to lower tuition fees — just like what happened to U of T’s international PhD students in 2018.

“The saddest part is knowing that there’s something that needs to be done, and that action not being taken,” Githumbi told me.

So, my only remaining question now is this:

What are we waiting for?