When Madeleine Thien began working on what would become her latest novel, she felt drawn to Cambodia but was unsure where the story lay and whether she could take on the country’s painful history. Writing became about finding a character who could lead her through the novel.

As Dogs at the Perimeter opens, we meet Janie, a neurology researcher in Montreal who has left her husband and son to live in the empty home of her friend and mentor, Hiroji Matsui. At first, Janie’s desertion is enigmatic: she is having a breakdown though its cause is a mystery. As the novel progresses, it becomes clear that Janie is confronting the trauma she incurred 30 years earlier as a child in Cambodia during the brutal Khmer Rouge regime. Her memories from that time have come flooding back as she sorts through the files left by Hiroji, who has left Canada for Cambodia in search of his brother James, a Red Cross doctor who went missing during the Khmer regime.

A primer: The Khmer Rouge held control over Cambodia from 1975 to 1979, during which time it instituted a social engineering policy that sought to destroy all aspects of the former culture so that a new, revolutionary culture could take its place. The cultural relics that were outlawed included religion, money, and the concept of the family. Professionals, the merchant class, artists, and intellectuals were executed. This initial purge was the beginning of what would become the widespread use of torture to root out “enemies”: anyone thought to harbour counter-revolutionary sentiments. At the same time, the Khmer Rouge pushed for Cambodia to become a purely agrarian society. In a single day Phnom Penh was abandoned. Citizens were forced into rural work camps as part of the regime’s impossible effort to become a completely self-sustaining society.

The Khmer Rouge’s reign of terror amounted to genocide. Death tolls vary, but most estimates range between 1.4 and 2.2 million dead. The causes of death range from torture and execution to exhaustion and starvation to succumbing to the most curable of diseases. That the numbers of dead do so vary speaks to how much of that history remains unresolved. Janie’s story, though fictional, is emblematic.

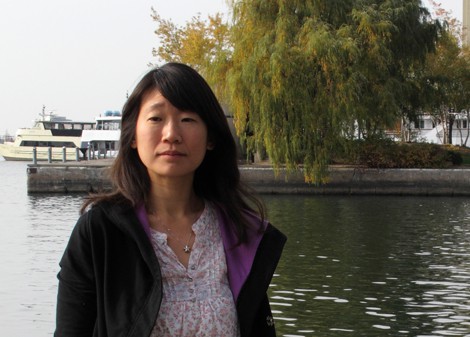

Madeleine Thien’s previous works of fiction include Certainty, a novel, and the story collection Simple Recipes, both of which were published to critical acclaim. She spoke to The Varsity in October.

———

[pullquote]What happened to people who were there from ’75 to ’79 is so beyond what a person could imagine. They lost things that we could never really comprehend.[/pullquote]

THE VARSITY

When did this book come about? Was there a gestation period, or was there a clear moment of inspiration?

MADELEINE THIEN

It was a long period of gestation. I’ve been curious about Cambodia for a long time and drawn to it as a place, as a country, and as a kind of unresolved history. I’d actually travelled that entire region without going into Cambodia because I always felt when I went I wanted to just go there. I didn’t want to be passing through on my way to Vietnam or going around on my way from Malaysia. So finally in 2007 I had a chance to go there for about six weeks, and I just travelled. It’s not a big country and you can travel from one end to the other in maybe eight hours, and it’s not that the distance is that long, it’s that the roads are so poor. I didn’t write. I just soaked it up. Then the next year I came back for five months, and that’s when I started writing. But even then, I wasn’t sure what I was writing. I was just writing to put some pieces together.

THE VARSITY

Is that the process that you tend to go through? There are some writers it seems who know what they want to write, make a plan, write the book, light edit afterwards —

MADELEINE THIEN

[wistful]

Yeah.

THE VARSITY

— and then there are other writers who seem to find out what the book is through the writing. Are you the latter?

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes, I’m the latter.

THE VARSITY

So it sounds like you had an interest in Cambodia for a while before it became clear it was going to become the subject of a book.

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes.

THE VARSITY

I’m also interested in this other aspect, the neurology side of things. Did you come at that in a similar way? Which came first as the subject of the book, the neurology or the Cambodia aspect?

MADELEINE THIEN

Ah, that’s interesting. They both seemed to exist for a long time. I didn’t know if they were connected. The neurology interest is very old. A general interest in science started when my mum passed away, which was 2002. I started reading a lot about science. A lot about biology, a lot about the mind. It seemed to be asking some big questions that at the time I felt I couldn’t find in fiction. You know, those really basic childhood questions: “What am I? Why am I here?”

THE VARSITY

“Where does a thought come from?”

MADELEINE THIEN

“Where does a thought come from? Where does it go? What happens when the body shuts down? What happens to the mind?” In neurology [those questions] are so fundamental to the science. It’s interesting to me in terms of philosophy instilling those questions and neurology trying to answer them in small pieces, and with the kind of humility as well that you might not be able to answer that larger question, but you can find out a little bit about the process.

When I started writing about Cambodia, I really just wanted to know what people did with these other lives that they had lived, if they had survived the Khmer Rouge; and if they had left the country — as so many did — and even when they remained, how much had to be forgotten; and what happened to those thoughts, what happened to those experiences?

What happened to people who were there from ’75 to ’79 is so beyond really what a person could imagine. They lost things that we could never really comprehend. So I wanted to know how people reinvented themselves after that, or how they managed to live with those things side by side, or not. A lot of that is, for me, linked to the process of remembering, the process of thinking, the process of forgetting. All of those things.

THE VARSITY

The period of that massacre is so recent that I would imagine that to write about Cambodia is, to some extent, to write about what happened then. There just hasn’t been enough time, I would suppose, to not address it, even if you wanted to, say, write about the present. Did you know immediately that it was this period that you wanted to tackle?

MADELEINE THIEN

I thought I would be writing about the aftermath of that period. I didn’t actually think that I would be able to write about ’75 to ’79 exactly, the Khmer Rouge. I didn’t think I could, for all sorts of reasons. So hard. And not a lot of readers necessarily want to read about that, you know? But I realized as I was writing that it’s almost impossible to write about the aftermath if the reader isn’t aware of what happened in those four years and the lead-up to it. There is no common foundation of knowledge to draw on because it’s one of those genocides that seems to be known at the basic level — when you say “Khmer Rouge,” people know — but after that, there’s not a lot of knowledge. So how do you write about the aftermath or how do you write about Cambodia post-that or how do you write about Cambodian refugees if what they went through stays invisible?

The thing I had to wrestle with was how to convey what happened. How do you find words for something like that? And how to tell it in a story that the reader won’t put down the book.

You make a lot of decisions along the way of how to give this experience to the reader but you really want the reader to keep going with you and stay with her [Janie] no matter how difficult it is. I guess every writer would come to that balance in a different way.

[pullquote]I’ve been fighting against this idea that it was a kind of madness. If you create the conditions for civil war, that civil war is going to be bloody, and things come out of a civil war that become unforgivable.[/pullquote]

THE VARSITY

On the Dogs at the Perimeter website, you have a video that you made, and I noticed one of the audio clips that you quote is from John Pilger’s documentary Year Zero, the subtitle of which was “The silent death of Cambodia.” That documentary was revolutionary in terms of the aid that resulted, but do you think many people know what happened in Cambodia?

MADELEINE THIEN

No. No, I don’t, and they also don’t know how involved our governments were. They don’t know it’s relationship with the Vietnam War, or about the way Cambodia was bombed. It’s something like 1.5 million tons of bombs were dropped on Cambodia to smoke out the North Vietnamese.

THE VARSITY

On the personal orders of Kissinger and Nixon.†

———

† Pilger opens Year Zero: “At 7:30 a.m. on April 17, 1975 the war in Cambodia was over. It was a unique war, for no country has ever experienced such concentrated bombing. On this, perhaps the most gentle and graceful land in all of Asia, President Nixon and Mr. Kissinger unleashed 100 thousand tons of bombs, the equivalent of five Hiroshimas. The bombing was their personal decision. Illegally and secretly, they bombed Cambodia, a neutral country, back to the Stone Age.” Twenty-one years after Year Zero aired, Bill Clinton released United States Air Force data detailing bombing sorties conducted over Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) between 1964 and 1975. As of 2006, there were still several “dark” periods in the database. Nevertheless, it showed that the bombing of Cambodia was far more extensive than previously reported: 2,756, 941 tons of bombs were dropped on the country, a campaign that began under Nixon’s predessor, Lyndon Johnson. See Taylor Owen and Ben Kiernan, “Bombs Over Cambodia” (The Walrus, October 2006).

———

MADELEINE THIEN

Yeah, exactly. They don’t know that the government that lost to the Khmer Rouge, the Lon Nol government, was completely funded by Western interests. They don’t know that when the Khmer Rouge finally fell to the North Vietnamese, we didn’t support this change because we didn’t want to support a Communist Vietnamese influence in Cambodia, and we actually funded the Khmer Rouge to keep fighting. That’s why all the aid, as Pilger shows, went to the border. It didn’t go into Phnom Penh, it didn’t go into the country. If you needed aid, and this was after four years of famine among other horrendous things, you had to get to the border, which then created these camps of millions of people who were too afraid to return to their country. The only good prospects you had were to go abroad: to go to France or Canada or the U.S.

You know, the Khmer Rouge held that U.N. seat until the early ’90s.

I think we’d like to think that it’s isolated to that part of the world and is a kind of madness. I’ve been fighting against this idea that it was a kind of madness. If you could create the conditions for civil war, that civil war is going to be bloody, and things come out of a civil war that become unforgivable.

The thing is, in a novel it’s hard to put all that history into the page. Because in the novel you just want people to experience this person’s life, this character. And so I made a conscious decision at some point that the history is there, and everything in the book, as far as I’ve known, is historically accurate, but there are things that I hope the reader would then look up, because we live in an age when it’s so easy to Wikipedia. If there’s some piece that you don’t know, I really hope that you would want to know.

THE VARSITY

That must have been a pretty difficult balance, though. You must have done a lot of research, which I can imagine would not have been easy research to do, not easy stuff to read, stuff to look at.

MADELEINE THIEN

Right.

THE VARSITY

And I could understand the impulse to pay testament to all the things that have come in through your eyes. But, as you say, you try to focus on a single life and a single character and to use that to draw the reader through the story. How did you find that balance?

MADELEINE THIEN

She kind of lead, you know?

THE VARSITY

Yeah?

MADELEINE THIEN

I knew that we were coming at a certain breaking point; I knew that Hiroji had disappeared — all these things I knew at the beginning when I started writing — but I didn’t know how that would lead her back, and if it could. Even now, that Cambodia section that she remembers, which is quite contained, I don’t know if it’s her retelling the story, or if it’s simply a set of memories that exist in her mind that she doesn’t replay but that are there and underlie so many of the things in her present life. But whether she actually sees it unfold the way we do, I doubt it. I think it’s just what’s in her mind.

As I was writing I thought she doesn’t have a way back — there’s just no way back for her — but the way that she tries to make sense of what she lived through is to take her experience and be able to tell someone else’s story. That she can understand what happened to James and what Hiroji feels in a way that no one else can, that’s what she tries to make from her experience. I think she lets go of the idea that she can salvage something of her own past, though I think she does, but really it’s about this act of friendship, it’s about her being able to say “I actually deeply understand what it would be like to give up your name and your identity and become a new person because there’s no way back.” That’s the heart of the book.

So I would say that to find that balance I just followed her. It seems like this is where she was going.

[pauses]

I learned a lot. It’s weird, you know, to talk about your characters like this, but it seemed that there was no other way for her.

[pullquote]I thought a lot about wouldn’t it be better to write a longer essay about what’s happening in Cambodia now? The thing is, I’m a fiction writer. I had to think about what fiction could do that non-fiction couldn’t. What I was looking for was what couldn’t be said. [/pullquote]

THE VARSITY

Did you start writing from what the reader would recognize as the beginning of the novel and then worked your way through it?

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes.

THE VARSITY

So at what point did you have the sense that she had taken the reins?

MADELEINE THIEN

I think at the Cambodia section.

THE VARSITY

Was there something specifically that surprised you that she did or a memory that she had that you didn’t see coming, and that was the point that she took over?

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes. There is a point where they’ve been pushed out of the city and then we suddenly know that her father disappears, but there’s not a lot of detail. We kind of see that scene where he gets put on the truck. It’s interesting because I felt on the one hand that she had taken the reins, and on the other hand there were things that she could only go so deeply into and she had to pass over. That’s the strange thing about this book for me is that it was a lot about following them, but also a lot about the things that couldn’t be said.

When I was writing this book I thought a lot about wouldn’t it be better to write a longer essay or something about what’s happening in Cambodia now with the tribunal? Wouldn’t it be better to focus on the challenges, really brutal challenges, that are facing the country right now? The thing is, I’m not a non-fiction writer. I’m a fiction writer, and so I had to think a lot about what it was that fiction could do that a non-fiction piece couldn’t do, and what’s mostly come out of the Cambodian experience have been witness accounts. There are extraordinary books about people who have survived. What I was looking for was what couldn’t be said. There are things that you can survive, and you can tell your story, but there are also things underneath that story that are so heavy it’s hard to find the words. I think that’s what I was looking for.

THE VARSITY

When they’re on the boat, I think you actually write, “There are no words for what happened on the boat.”

On the sea, we moved through a turbulent world, forever adrift. Three or four nights passed, but each day no land appeared on the horizon. On and on we went until the night when the men came. The collision hit like an explosion. Once, these men had been fishermen, but now they were something else, some instinct that has no pity, no name. They robbed us, and then they forced the girls up out of the cargo hold. I remember the sound of crying, a noise like a serrated edge. Minutes passed, hours. I remember crawling between the bodies to the edge of the deck, away from the smell of fuel, but still the men were there. Pulling us back, taunting us. Time stopped. I have no words for what was done.

I’m wondering, in terms of the writing process, was that something that you just couldn’t write? Or did you kind of write by elision, write by editing out what happened?

MADELEINE THIEN

That’s a good question. I don’t think I edited out. I think she came to a point of memory that just couldn’t be breached. I think she didn’t have the words. I think that she can only go so far, you know? Some things maybe are not meant to be shared. That’s what I felt with her, and I’ve been criticized on that point, but I feel that it was true to her and true to the story.

THE VARSITY

It’s almost a matter of privacy, in a strange way.

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes, that’s right.

THE VARSITY

Privacy admittedly for someone who is fictional.

MADELEINE THIEN

I know. I feel the same way.

[pullquote]You would have to pick up on how terrifying it would be to celebrate the connections between people to know what an incredibly courageous thing she has done for herself. It’s an act of defiance in every way. [/pullquote]

THE VARSITY

Something that I was thinking about, a strange kind of tension along the same lines of what we’ve been talking about, is that I’m used to with a lot of survivor literature, be it the Holocaust or something else — various atrocities from the 20th century — the underlying principle seems to be “I’m going to write down what happened, and I’m going to write down every detail, whatever happened to me.”

They are throwing us away, she wrote, and I can’t understand why because all I wanted was for the war to end, no matter who won. I never admitted any allegiance. My name is Sorya. I am the sister of Dararith, the daughter of Kravann and Mary, the wife of James. I was a teacher.

This person might be dead, and admittedly, writing is no consolation to the dead, but to pay testament: “This person existed. They lived there. This is what happened to them.” Tell their life story, and that is a testament to their life.

But in the case of Cambodia, I feel that’s almost been turned inside out in a way, because the regime made such a point of getting people’s biographies, and in fact that was such an aspect of the torture that these people went through.

Angkar [the Khmer Rouge government] had been obsessed with recording biographies. Every person, no matter their status with the Khmer Rouge, had to dictate their life story or write it down. We had to sign our names to these biographies, and we did this over and over, naming family and friends, illuminating the past. My little brother and I were only eight and ten years old but, even then, we understood that the story of one’s own life could not be trusted, that it could destroy you and all the people you loved.

*

His interrogator asked Prasith to give a biography and to name all the remaining members of his family. Then he had to repeat his life story, over and over.

…

In the prison, the interrogator’s job is to trace all lines to the enemy, to lay bare the networks of connection, and then to follow this taint to every corner of the country. My brother was taught to do this methodically, calmly, without losing control. Chea kept track of the names that surfaced during each prisoner’s interrogation. He noted them in a ledger, then he sent messages to the cooperative leaders: a sheet of white paper, folded four times, containing only names, a date, and the place of the summons.

*

James would sit with his arms tied behind his back while the man probed him, as if his life story were a confession, as if the two were the same thing.

There’s such pain tied to that experience. I think that might be partly why people have just wanted to reinvent themselves, and let go.

But the novel is telling someone’s life story. Was that a tension you grappled with? And how did you deal with that? It goes back, I suppose, to that idea of telling her story through somebody else.

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes. You would have to pick up on how terrifying it would be to set something down on paper and to celebrate the connections between people to know what an incredibly courageous thing she has done for herself. It’s an act of defiance in every way.

Yes, that your own life story could be so dangerous, not only to yourself, but to everything you cared about: among many things, it’s a really horrific part of the regime. And then you think of these children, and within the families themselves, that they couldn’t acknowledge each other. Parents literally had to watch their children being taken away and not show grief or pain, and then it’s very easy to manipulate the children into thinking “Your parents can’t protect you, and don’t even want to.” The whole thing is so insidious. But you’re exactly right. It’s about how just telling someone’s story can be a brave act.

THE VARSITY

The suppression that has to go on to not show grief — when I was watching Year Zero, there are so many scenes in that documentary that stay with you, especially looking at sick children, but one of the scenes that stayed with me was when he [Pilger] is talking to the interrogators.

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes.

THE VARSITY

He’s asking them “What was going through your mind when you were torturing these people? Did it not strike you that these were fellow human beings?”

[To the interpreter:] Would you ask this man here what he must have thought when he was killing all these people, that he was killing fellow human beings, fellow countrymen.

What stays with me is the lack of facial response to that question. I was wondering about the challenges of not creating villains in your book. Because how the interrogators respond is “If we didn’t do this, they would have killed, they would have done the same to us.”

Interpreter: He says that if he does not kill these people, the higher commander killded [sic] him.

In your book the interrogators end up in prison themselves and end up being interrogated. No one really escapes this cascading violence.

MADELEINE THIEN

That’s right. It’s very much like Stalinism: It starts to eat its own. Even the top echelon of the Khmer Rouge — even the ones who had started off fighting against the French in the ’50s and were part of this long resistance — they also ended up in these prisons. Because no one could be trusted. The idea of “the enemy” was rooted so deeply in the regime’s ideology.

I also think that something happens where if you believe in the system, you have to believe that the people brought to the prisons and interrogated are guilty. There was a sort of automatic assumption of guilt, and you think people really felt, up until the last moment, that they would be protected by the regime because they were true believers and that they were pure of heart, and all along the way they persuaded themselves that everyone else who fell into these prisons was not. I think that’s a very human response.

He was the youngest of all the interrogators and Chea told my brother that he should be proud. There are many prisons like ours, Chea said, all over the new country. The interrogators were pulling truth from the bleakest corners, they were the hands and the eyes of Angkar, they were the ones, the only ones, who refused deception. “Don’t be afraid,” Chea told him. “You have a strong character and an upright mind. They can’t harm you.” He said it was my brother’s goodness that cut the prisoners. It was his honesty that sought the truth.

…

Kosal had betrayed Prasith before he died. The teenager was corrupt, Kosal had said, his only aim to sabotage the revolution. He had gone to school in Phnom Penh, his father had worked as a driver for the French Embassy. All this time, Prasith had kept this information hidden. … He was a traitor of the worst kind, an insect to be purged, a boy who had always put his own survival first. My brother knew this was true. Somehow, Prasith had never completely believed. Maybe Angkar was right, maybe the country had always been most vulnerable from within.

It’s hard to dismantle belief. If you already have the scaffolding in place, it’s hard to start removing it, because the whole thing collapses. And yes, this thing of not showing expression: you know, you commonly hear in survivors’ accounts that if you want to survive, you have to disappear. So what happens to an entire population of people who have learned to disappear? It’s not so easy to then appear back to yourself, to reclaim what you were before.

[pullquote]People really felt, up until the last moment, that they would be protected by the regime because they were pure of heart, and all along the way they persuaded themselves that everyone else who fell into these prisons was not.[/pullquote]

I’ve found that it’s a hard book also in the sense that for people who are very familiar with what happened in Cambodia — historians, children of survivors, survivors — they’ve been able to read all the nuances of the book. It’s harder when you come with less background knowledge. But a part of me wanted to tell the story for people who —

[pauses]

There have just been so few stories. My entire collection of books about Cambodia, and I think I have most of them, it’s no more than two shelves of books. It’s really not very much.

THE VARSITY

At least in English.

MADELEINE THIEN

In English.

THE VARSITY

Would there be much more in other languages?

MADELEINE THIEN

There’s a bit more in French.

THE VARSITY

Because of Cambodia’s history as a colony?

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes, and because quite a lot of refugees went to France afterwards. For the people who stayed in Cambodia, for the next 20 years they were just trying to survive. I think you need a certain amount of space and support to go back and start looking at what happened. I don’t think they had that in Cambodia itself. This war crimes tribunal is the first time. That system itself is very flawed, but it really is the first opening that’s given people the chance to look back.

THE VARSITY

At the event on Friday you mentioned that one of the motives of your writing is that you are interested in your generation and the experiences of your generation.

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes.

THE VARSITY

How do you think the Cambodian genocide has played into your generation’s consciousness? Do you have personal memories associated with that event and its aftermath?

MADELEINE THIEN

I remember the refugees arriving. I don’t remember Cambodia itself. I was born in ’74, so by ’79 I would have been five. But it was around ’84 and beyond that really huge numbers of people were arriving in the U.S., also in Canada and France. I don’t know what it was that I saw or read or was to exposed to, but it was the first time as a child that I recognized that my experience was such a small part of the entirety, which is I think a really big realization as a child. That there were so many other things that these children my age had experienced and lived and understood that I had been closed off from, or protected from.

Then these children were put into my world, in a sense, in schools that were familiar to me, but for them, they had to become someone new all over again. I think as a child I couldn’t wrap my head around it, and I still can’t. I still find it extraordinary what people bring from other lives, and in some way how they’re expected to make that disappear. We also ask people to reinvent themselves, and I think it is a healthy thing, but at the same time, it allows us to remain a little bit blind to things. It’s a big question.

[pullquote]What happens to an entire population of people who have learned to disappear? It’s not so easy to then appear back to yourself, to reclaim what you were before.[/pullquote]

THE VARSITY

When Janie is on the boat — I recognize that she didn’t get to here on the boat, but it did put me in mind of boat people.

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes.

THE VARSITY

Images of boat people continue to be powerful because that migration speaks to the kind of desperation that goes with various concerns around the world.

MADELEINE THIEN

It speaks to the present, yes. Proxy wars, the massive destabilization of regions: these are things that seem to be in our easy capacity.

As I’m travelling [touring literary festivals, talking about the book] I’ve been put on a lot of historical fiction panels. I don’t mind, because it is history, but at the same time I think, “This is my generation.” It can’t be history yet, especially as it’s repeating and repeating and repeating. There are things that are so relevant to now.

THE VARSITY

Another of your characters, James, has been through trauma of his own. He has the trauma that he goes through in Cambodia, but also his family is from Tokyo. He has early memories of the war. Maybe we should talk a bit about where each of these characters came from. How did Hiroji come about?

MADELEINE THIEN

In my mind?

THE VARSITY

Yes.

MADELEINE THIEN

I don’t know.

THE VARSITY

Or who came first? Was it Janie?

MADELEINE THIEN

They came together.

THE VARSITY

Oh, okay.

MADELEINE THIEN

Yeah. [laughs] They came together but I wasn’t sure — I think as I was writing, their ages changed. I realized they were actually two different generations. It was more of a mentorship and friendship, but the mentorship part of it came later when I realized that there was a larger difference in age.

I don’t know. I’d had an idea of a character who walks out of his life and goes in search of someone, but it was pretty vague. You know, it was quite a generic thing.

THE VARSITY

It’s funny, because when you phrase it that way, Janie also walks out of her life and goes —

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes.

THE VARSITY

— in search of someone. It’s kind of like an echo.

MADELEINE THIEN

They’re doubles in a sense, yeah. Except that she has nowhere. The difference between them that moved me was her knowledge or her belief that you can’t go back and find these things, and his, because he hadn’t lived through what she’d lived through, that there could still be survivors. I think she wants to rid him of this belief, because of friendship, because of love. “You have to let go and move on.” She knows she had to let go and move on.

THE VARSITY

He discovers that you can find the person that you think you’re looking for, but that person might not really exist anymore.

MADELEINE THIEN

That’s it. It’s hard thinking back to the way that they came because it is that weird thing of writing a novel over time: it seems they were always there. You forget the building. Also, for me, I never see it as creating characters. I feel as if they’re there and I’m the one who has to get to know them. So it’s not so much building as trying to see clearly.

THE VARSITY

The relationship between Janie and her son is really interesting as well. When you were talking about neurology and the big questions, that really put me in mind of those two, because Janie’s son is quite young and he does ask the big questions, and because he’s a child — kids do that thing where they don’t know yet what not to ask.

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes.

THE VARSITY

I found that their relationship drew out a lot of what Janie is going through. She’s having something of a breakdown. She can no longer contain what’s been inside her for the past decades, and that has a physical expression as well. She has something with her hands.

In the apartment I turned the heat up high, but still my hands shook. The water came to me, everywhere, loud. Something had spilled on the kitchen floor and Kiri was walking through it, running, stamping his feet. I asked him to stop. My thoughts didn’t fit together. I heard noises all around us, I saw shapes coming nearer and Kiri shouting, oblivious. Stop, I said again. I tried to leave but he gripped my hands. I pulled away, but he was holding my clothes. I tried to free myself. In a moment of wildness, he grabbed a handful of forks and threw them down into the mess. The noise seemed like the ceiling crashing down, falling on top of us, blocking all the light. I raised my hand and hit him, once, twice. I cannot remember it all. And then, in an instant, the noise disappeared.

…

It was January, and the ice covered everything and I didn’t know anymore, I couldn’t explain, how this could have happened, why I could not control my hands, my own body.

Was that physical experience something you came across in your research? Or was that something you imagined?

[pullquote]I never see it as creating characters. I feel as if they’re there and I’m the one who has to get to know them. So it’s not so much building as trying to see clearly.[/pullquote]

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes. Not that, specifically, but these people that had carried on so courageously, hitting this point where it wasn’t possible anymore. Why at this point was it no longer possible? That comes up again and again, not in survivor accounts but it comes up in scientific literature, long-term studies of trauma, and specifically of Cambodian communities in the U.S.

Another branch of what I was thinking about was where that violence goes. Yes, it’s true of survivors, but it’s also true of people who come from violent families. There’s that fear of what you now carry and fear of something that’s embedded in you.

THE VARSITY

Violent families, families where there’s some sort of substance abuse.

MADELEINE THIEN

Exactly. That’s what kind of broke my heart with Janie, because she’s actually afraid of what’s inside herself.

THE VARSITY

She’s really trying to protect her son.

MADELEINE THIEN

She’s really trying to protect him. It’s so lightly drawn in the book, but I felt part of what she also sees is that in trying to protect him she’s also pulling away from him, and children sense this right away. The more you try to pull away, the more they want to hold you close.

THE VARSITY

He says, “I’ll stop doing whatever it was I was doing.”

Our son didn’t understand and I saw that he blamed himself, that he tried so hard not to be the cause of my rage, my unpredictable anger. He aspired to a sort of perfection, as if it were up to him to keep us safe. We sat down with Kiri. I told my son that the only person to blame was myself. I told him that I had to go away for a little while.

“No,” he said to his father. “Please don’t do this. I take everything back.”

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes. And she knows what it is to have the outside world encroach so brutally on a person’s life that the child is not at fault but they don’t understand and they try to take on this responsibility, as she does for her mother and her brother. She’s complex. I’ve always felt that, yes, she does all that she does out of friendship for Hiroji, but it’s also so that she can find a way back to her family. That’s the large thing that’s pushing her to look at things.

THE VARSITY

I found that there was a lot of water imagery in the book. There’s oceans and there’s rainy seasons, and there’s just the simple fact of people wanting fresh water, but Janie works at a reservoir at one point at one of the camps, and I think there’s also a lot of images of overflowing.

Thida disappeared, then Chan, then Srei. Other children arrived to replace them. Su, Leakhena, Dara, every one of us like water spilling into the ground.

*

She doesn’t wear makeup anymore but her hair is still long. Unbrushed, it floods around her and it seems, to James, as if it eats the light and hides the things that no one says: I married you as a favour to Dararith, I married you because of the war, out of loneliness, out of fear. I love only you. They both think these things, they both hold themselves in reserve.

*

When Chorn returns at nightfall, James says, “What is this?” He has to control every word or they will overflow and hurt him. He says again, “What is this?”

*

There is water everywhere, he cries until all the rest comes out, all of it spills onto his ragged shirt, onto the tiled floor, and seeps into the cracks that lead out of the store room. There is no wind in this room, no oxygen. Where is emptiness? No matter where he goes, he can’t find emptiness.

“Do you believe him?” Kwan asks.

James, wherever he is, trickling across the ground, spreading down to the lowest places, says no.

What did the water mean to you as you were writing the book? Was it something you were conscious of weaving in?

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes and no. I was really conscious of it with Sopham. He’s always thirsty. He’s very aware of the thirst of the prisoners. And water is such a simple and powerful thing. Actually, water was a big part of what the Khmer Rouge focused on. They really thought that if they could build these enormous reservoirs and have enough water to feed the fields for three different rice crops, they would become masters of their country. It was all about self-sufficiency, and self-sufficiency was about getting enough water.

The image that stays with me of Janie is just her being alone on the ocean — how extraordinary and big and terrifying; and how minute she becomes — and wanting not to float. And yet she floats and floats.

Sopham appeared and we fell into the sea. I fell, I kept falling, and then my body rose to the surface. … I no longer wanted to breathe the air. My brother kept repeating my name. He used his krama to tie my wrist to a piece of floating wood, checking and rechecking the knot. Don’t leave me, I said. … I said that I could not bear to be alone. My brother wept. I was not strong enough to hold him. He opened his hands and I watched as the ocean breathed him in.

I saw my wrist and my hand bound to the wood but I no longer recognized it as my own. The knot my brother had tied would not come loose. Inside me, all the feeling went away.

This is Janie’s perception of her life: even when she tries to go down, she can’t. At one point she walks and walks and she gets to the river [the Rivière des Prairies, which separates the Island of Montreal from Laval] and she doesn’t know whether she wants it to take her or not. There’s this incredible sorrow with her that she floats, that she somehow remains. I don’t know how it all resolves, but you’re right, this idea of water…

THE VARSITY

There’s also that moment, when she gets the phone call from the archivist about they found these letters —

MADELEINE THIEN

She spills the water!

THE VARSITY

— she tips over the water and there’s like this puddle that she has to mop up.

[both laugh]

MADELEINE THIEN

This I think this was unconscious! That’s really interesting. It’s true, it’s true.

THE VARSITY

You have a couple settings that you’re working within. We’ve been talking a lot about Cambodia, but I’m also wondering about Montreal. This is somewhere you’ve lived. Did you choose that place or did it choose you? Did you pick it simply because you knew it, or was there something that made Montreal really work as a secondary setting?

MADELEINE THIEN

Ah. It seemed to choose itself, partly because the Brain Research Institute is based on the Montreal Neurological Institute. Even the architecture of it, the lobby, everything is very much the MNI. I didn’t want to upset them in any way [laughs], so I fictionalized mine. But I spent a lot of time there.

It leant itself well I think because of the solitude of winter, the harshness of winter and in a way it was about as far away as she could be from the landscape of her childhood because Cambodia, it’s incredibly lush. Things grow. Sensually, it’s really an extraordinary place.

THE VARSITY

I think you mention gamboge —

MADELEINE THIEN

The colour.

THE VARSITY

— the word has the same etymology as Cambodia. [In Latin the colour is gambogium, from Gambogia, the name for the country.]

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes, that’s right. The flavours of things. It’s a very sensual place. I think it’s the reason people have always been drawn there. It engages all the parts of your mind and your eyes and your ears and your smell. Whereas winter —

THE VARSITY

Draws you inward.

MADELEINE THIEN

— draws you inward! Yes! You can’t even smell anything but the cold, and everything is waiting for a very long time for light and warmth again. I think that’s it: it just leant itself very much to her psychology. I never thought about it.

THE VARSITY

That’s interesting, because another one of the books I’ve been reading of authors who are at the festival is Dany Laferrière’s The Return. He’s writing about Haiti, but there’s also a similar distinction between the two places; he also writes about Montreal and it’s winter —

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes.

THE VARSITY

— and it has that similar contrasting of the psychology of setting.

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes. In winter I’ve found you live in your mind in a different way because you need to feed yourself, you know?

[laughs]

THE VARSITY

Yeah.

MADELEINE THIEN

You need to feed yourself and your mind. I’ve been in Montreal five years and I still can’t wrap my head around winter. I really struggle with it and at the same time I see what kinds of doors it opens internally because you really can’t open the external door!

[laughs]

THE VARSITY

Yeah. There is a kind of sense in which winter is the hibernation period. I think your brain does do different things in that season.

MADELEINE THIEN

Yes, and if you’re alone when the season starts, it’s brutal. [laughs] You can’t even keep warm!

[both laugh]

Yeah. So all those things played in.