The Parsi story starts with an exodus. My ancestors left Persia a thousand years ago, fleeing religious persecution, and finding a new home in the coastal trading cities of the Indian subcontinent.

The exoduses of Parsis have continued since that first move. “The Parsis in the 1800s — more than the other Gujarati people, more than the other Bombay people, more than other Indians — travelled around the British colonies in the world for work because they were more skilled,” explains professor Enrico Raffaelli, who teaches courses on Zoroastrian history and culture at the University of Toronto’s Mississauga and St. George campuses. “And that movement was even more noticeable in the 1900s, so they went to Aden, Arabia or to Hong Kong or East Africa and England.”

Meherab Chothia is part of that tradition in a very direct way. “I am a chartered accountant from India, and I got an opportunity to work with the Toronto office on a six-month secondment. They liked my work and they wanted to have me on a permanent basis. They asked me if I was interested, I said yes, they processed my work permit and that’s how I ended up in Canada.”

Numbers and the quest for a higher birth rate

According to the rough numbers that circulate on websites dedicated to the community, there are some 150,000–200,000 Zoroastrians worldwide. Nearly half that number live in India, concentrated largely in the country’s commercial capital (and my hometown) Mumbai. But Leilah Veivana, a PhD candidate at the New School for Social Research in New York who studies land rights and the Parsi panchayat (community government), says it’s hard to be sure that those numbers are accurate.

“The demographic question is still so open,” she says. “For instance, I want to know if when a census worker comes to the house, and someone has their children in college in North America, for example, are they counting those children as the household? Maybe those children will come back, maybe they’ll never come back — who knows?

“In the diaspora, to my knowledge at least, no one is counting us, unless we’re members of organizations. I think my name is on the Zoroastrian Association of California’s rollbook, because that’s where my parents live. So the numbers are really unclear to me, especially with how many people are lost to immigration and whether intermarried people and their children are counted or not counted — it’s very unclear.”

Whatever the numbers really are, there’s no doubt that the number of children born to Parsi couples is dwindling every year. Intermarriage is a significant topic of contention for the community, and matchmaking services like parsimatrimony.com have gained significant followings. The panchayat, an elected body in Mumbai that administers vast plots of real-estate left to the community by wealthy Parsis, has a strict definition of ‘Parsi’ — an individual born of two Parsi parents, or whose father is Parsi.

Because my mother is Parsi and my father is not, I don’t fit that definition, even though I’ve always strongly identified with the community and had my navjote — a religious initiation ceremony — in 2006.

The young people of today

Nozer Kotwal has seen several generations of Canadian Parsis. “I have done navjotes of kids, then I did their weddings, and now I do their kids’ navjotes,” he says. “And actually, in the last couple of years I’ve even done their [the kid’s kids’] weddings — so you know how old I am!”

Kotwal is a dastur, a Parsi priest, one of a handful who performs navjotes, lagans (weddings), funeral prayers, and jashaans (ritual prayers) for the large Toronto Parsi community. The present generation of Toronto Parsis, he says, is less connected to the community’s religious and cultural roots. “I know the kids who are born over here, and especially those who have never visited India or Pakistan, they have a totally different disconnect. When we first came over here, the first generation was too busy settling down, so there was not too much attention paid to religion.”

Perry Baria is a first-generation Canadian; her family moved to Toronto from Mumbai when she was two. “I wouldn’t say my parents brought me up very Parsi, there were definitely some influences in terms of the food, I understand the language, I understand the culture, I had my navjote, we went to other people’s navjotes, we went to Parsi weddings,” she recalls. “We knew our relatives, but apart from that we didn’t really have a lot of interaction with the community.”

Baria has been back to India frequently, but she fits Kotwal’s description of the new generation of Toronto Parsis. “I haven’t really been part of the community, ever since I was little,” she says. “I stopped going to religious classes when I was 10 or 11 or something. And after that I didn’t really participate in any of the Zoroastrian functions.”

Centres of community

There is no agiary, or fire temple, in Toronto. The community does have two community centres, one in North York and the other in Mississauga. “Let’s call them ‘religious centres,’” says Rafaelli, who has attended ceremonies at both locations. “You can’t call them Agiaries, because they don’t have professional priests.”

Kotwal thinks establishing an agiary is crucial, and it needs to happen soon. “I honestly believe that if we do not establish something like an agiary over here, it’ll never get done,” he explains. “The kids have absolutely no concept whatsoever. But the other side of the coin is [that] you want to leave it for them, but if they don’t want to use it, what’s the sense?”

It’s part of the broader difference Kotwal sees between generations. “The kids’ attitude over here is that they would rather see something happen socially, rather than religiously. That’s the big disconnect between my generation and their’s — their priorities are very different.”

Chothia thinks that disconnect is a normal consequence of the differences between life in Canada and India. “In India, it’s more community-based, because there are so many events happening. The North American-Canadian lifestyle is … I wouldn’t say a lonely lifestyle, but everyone does their own thing…

“At an event at the [Parsi] Gymkhana [club] in Bombay, there will be hundreds of people who show up. That’s just a factor of being in a crowded place with 50,000 Parsis — any Navroze event, 5,000 people show up, as against 500 in Toronto.”

‘Parsi’ usually denotes a Zoroastrian from India or Pakistan. There are however, Toronto Zoroastrians who immigrated directly from Iran, without the thousand-year detour through India. Some attend events at the Toronto religious centres, but Chothia points out that they don’t necessarily form part of the Parsi community. “When I meet the Persians, obviously you see so many differentiating factors. They speak a different language. The only common thing is that they practice Zoroastrianism, but other than the culture and the custom is very different.”

Who gets in?

Most of the younger generation of Toronto Parsis are only dimly aware of the political battles being waged in Mumbai. “I really don’t know at all — I know about this Parsi panchayat, but I don’t really have any idea of who runs it, what it’s all about, who gets what from it,” Baria admits.

Rafaelli’s interaction with the community is itself a sign of the ‘reformist’ bent of Toronto Parsis. “I would say in both associations the majority are people who are open — I myself could attend the ceremonies in both centres with my students, and no-one protested about that.”

Marriage outside of the community is not as hotly contested in Canada either. “It is accepted more over here than in India,” says Kotwal. “In India also, it’s galore. I would say probably over there — mind you, I’m just guessing — but I think it is at least 50-50 over there, people marrying in and marrying out [of the community]. Whereas over here I would say it can go as high as 75-25.”

Both Veivana and Kotwal note that changes in gender equity have also affected the way Parsis in India see marriage. “Some young people say, ‘I’m just tired of all the fighting, I don’t know if I can find a Parsi person [to marry],’” Veivana notes. “Especially the young women I talk to — I don’t know whether it’s just a stereotype, but they say that the Parsi men in Bombay are not as educated as them.”

Kotwal also believes education plays a big role. “This generation is more educated. Before, with the girls, they went up to high school, and then their parents got them married, and many of them became housewives,” he says. “But these days, the women are well-educated — I think they are better educated than boys these days in India — and they realize, ‘Why should I settle down with this ignorant guy?’ They work, and they meet people at work, and they fall in love. It’s natural.”

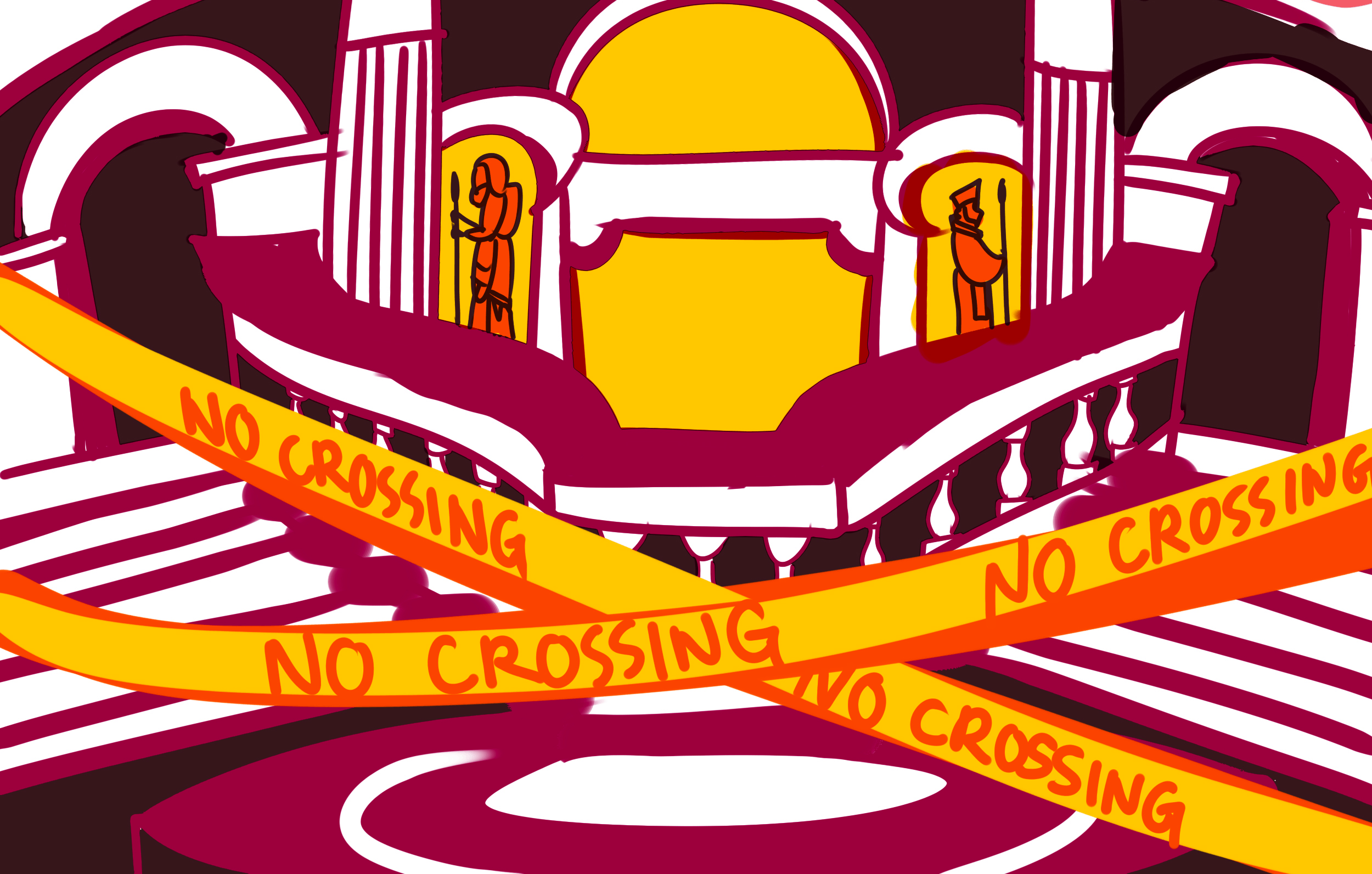

The increase in marriage outside the community and immigration from India has led to some fascinating questions of access and belonging. Agiaries are closed to anyone who is not a member of the community, and only Parsis can benefit from the subsidized housing administered by the panchayat.

Baria recounts an experience at a Mumbai Agaiary, when a priest stopped her from entering because she wasn’t wearing a sadra and kasti, the religious vestments that Parsis are supposed to wear following their navjotes. “ I didn’t really have any chance of going in there because: a) I didn’t speak the language, b) I had a Canadian accent, and c) I didn’t have a sadra and kasti.”

I’ve had my own difficulties entering Agiaries. The most frequent tactic used to keep outsiders out is to ask their names — if it’s not Parsi enough, you don’t get in. ‘Murad’ is a Parsi name, and I’ve made do by using my mother’s maiden name (Antia) in place of my own surname. But Veivana notes that immigration and outside marriage is making it harder to delineate who is and is not a ‘Parsi.’

“The allowing in is so arbitrary,” she says. “I have Parsi friends that don’t look typically Parsi, and they get stopped and asked, ‘Who’s your father? What is your father’s name? What is your surname?’ But it’s completely arbitrary. It’s within some range of what people expect Parsis to look like.

“I wonder when people come back to visit Bombay from the diaspora, from Australia or wherever, and if they’re from mixed parents, if that’s going to change somehow, there’s going to be more criteria to allow people in, or [for] showing some kind of identification.”

What’s the attraction?

Perhaps immigration is more of a pronounced phenomenon in the Parsi community because the community itself is so small — the less people there are to emigrate, the more significant each act of migration becomes.

Kotwal originally moved to Montréal. “It was a fascination with the Western world,” he explains. “You watch Hollywood movies, and North America fascinates you. I said, ‘let me try,’ and I got in.”

When Kotwal arrived, he was one of a handful of Parsis in Canada. “We were 25 altogether, when I first came. The first three months when I was in Montréal, I didn’t meet a single Zartoshti [Parsi].”

There are now several thousand Parsis in Canada, most in the Toronto and Montréal metropolitan areas, according to the community’s own numbers. Chothia says the presence of a tight-knit, large Parsi community in Toronto made the decision to move much easier. “The reason I decided to come to Canada is I went down to the darbe mehr [the community centre], in March, during the Navroze functions, and I saw so many Parsis, and so many Parsis from Mumbai. So I felt a connection, and that was one of the major factors that helped me make the decision to move to Canada.”

I suggest to Rafaelli that the original exodus from Persia created a nomadic impulse for the modern Parsi. He isn’t so sure. “I wouldn’t relate the fact that they’ve travelled around the world so much to the fact that they are a diaspora community in the first place,” he says. “I would more closely relate it to what’s happened in the contemporary modern times in the last century.”

The Class Question

Veivana points out that immigration is almost exclusively an upper-class phenomenon. “It’s very class-based,” she says. “Poor Parsis who live in sanitaria [panchayat-run shelters] don’t have relatives that are going to college abroad.”

The Parsis in India are associated with names like Tata and Wadia, titans of industry who own multi-national corporations with brands like Jaguar and Tetley Tea. But there are still poor Parsis. “I think it’s very consciously embarrassing for the panchayat when things about very, very poor Parsis come out — and for the community, it’s very embarrassing when people write about that,” Veivana says.

“Of course in terms [of] contemporary Mumbai, Parsis are not poor like other people are poor… They’re just not; according to the census, no Parsi is living in slums,” she notes. But the panchayat sets out a higher standard of living than the Indian government. “The panchayat last year said the criteria for a poor Parsi was someone who makes less than 90,000 rupees [about $1,700] a month. That’s about 14 times what is considered poverty in Bombay.”

Still, Veviana says, there’s a distinct difference between the class of Parsis who can afford to immigrate and send their kids to universities abroad, and those that live in subsidized housing on community land. “There is still a huge divide between the poorest Parsi living on the panchayat dole and someone who’s living in a high-rise flat somewhere, with connections to Parsi diaspora elsewhere.”

It’s an Immigrant Thing

I ask Rafaelli whether the act of immigration has made Toronto Parsis more open, or whether it’s possible that the reformist sections of the community are more likely to immigrate. He’s not sure. “I think that they’re forced to become liberal when they come here, because I don’t think the situation is such that they would leave in order to find more liberality. It might be if we studied sociologically and psychologically that people who are more liberal are open to leave one’s country. But that is a type of analysis that would apply not only to Parsis, not only to Zoroastrians, but to all diaspora groups.”

Chothia points out that immigration is a challenging experience for anyone, Parsi or not. “It’s not easy to move countries; it’s a big change.”