The University of Toronto’s Medical Sciences Building was built in the late 1960s, at the height of the university’s Brutalist architecture fad. Last week, part of the roof between the main building and the JJR MacLeod Auditorium fell in. The Medical Sciences Building tops the university’s deferred maintenance list, with some $54 million in outstanding repairs.

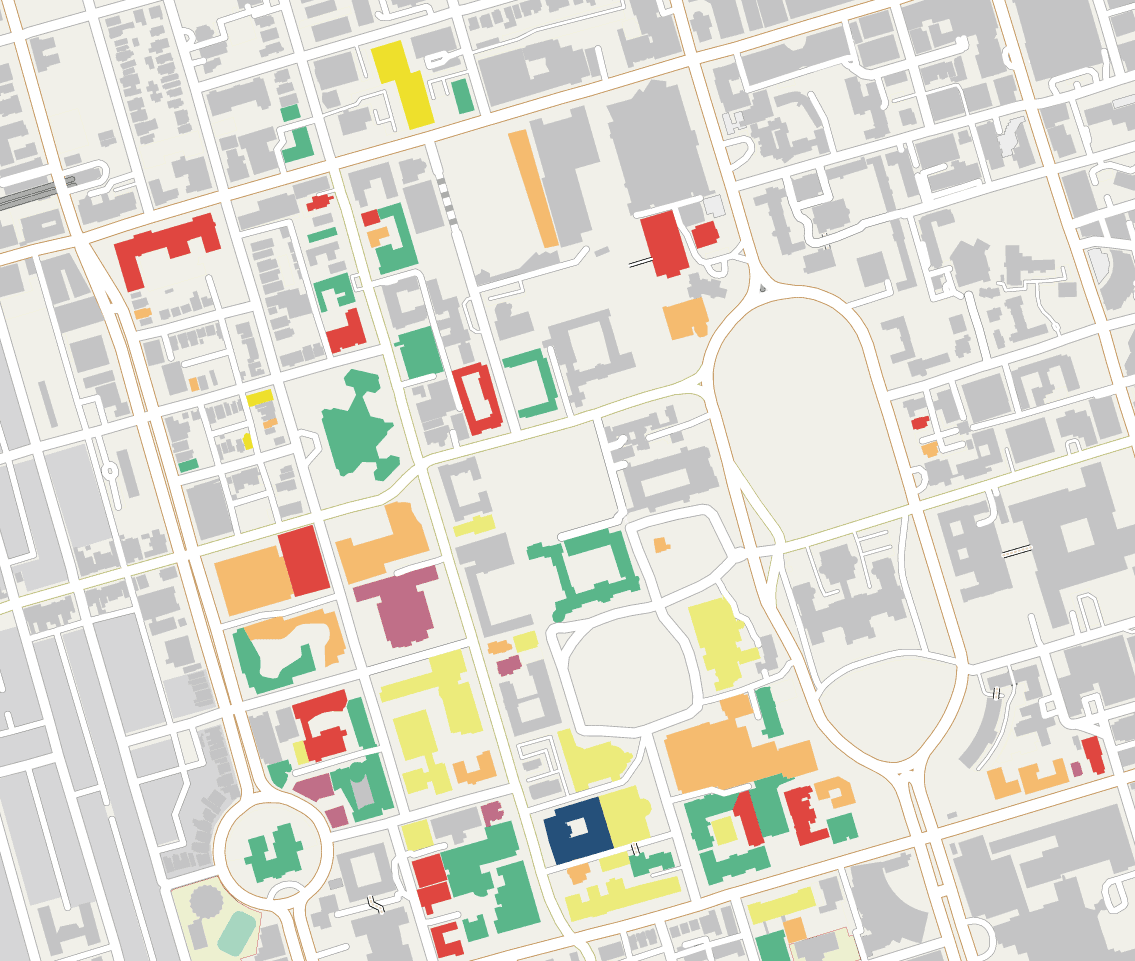

INTERACTIVE: Maps of the deferred maintenance on University of Toronto’s three campuses

U of T’s total deferred maintenance rose to $505 million last year according to a report presented at the January 27 meeting of the Business Board of Governing Council.

The half-billion dollar figure represents a $21 million increase over last year’s $484 million, but Ron Swail, assistant vice-president, facilities and services, and the report’s author, says that the university is moving in the right direction. “I think we’re managing the issue,” he said. “We haven’t seen as big a jump in the total deferred maintenance. That is because we’re getting money and putting it towards this issue.”

The Facilities Condition Index (FCI) is a measure of a building’s condition. An FCI of 10 per cent indicates a building or property portfolio in poor condition; U of T’s average FCI sits at 14.1 per cent, down from 14.3 per cent last year.

Swail emphasizes that the numbers in the report are “order of magnitude figures,” and should not be taken verbatim. The university’s deferred maintenance totals do not include the federated colleges of Victoria, St. Michael’s, and Trinity, which manage their own property portfolios.

The university deals with two kinds of repairs, explained Swail. Routine maintenance like replacing bulbs or fixing broken faucets is low-cost, and is covered under the Facilities and Services operational budget. Deferred maintenance issues are considered capital projects, which are “large in nature, and by definition they are things that are not routine — when you repair a capital item it lasts for many years, sometimes 20–30 years.”

Expansion and maintenance can go hand-in-hand, since maintenance work is sometimes undertaken as part of larger capital projects. This allows the university to reduce costs by using construction companies already on-site, Swail said. Such collaboration efforts include the renovations of 1 Spadina Crescent, the Munk School of Global Affairs, and the Lassonde Mining Building.

Swail also cited a section of the Jackman Humanities building roof that was paid for from the deferred maintenance budget, because it was not included in the original renovation plans. “A lot of what we’ve funded for maintenance is in the renovation projects, the capital projects that replace old and tired space,” said Scott Maybury, vice-president, operations, at the Business Board meeting.

The emphasis on expansion is also a result of provincial funding structures. “The province likes to fund new projects, new buildings while deferred maintenance bills go up,” Maybury said.

Ben Coleman, a member of the UTSU’s board of directors and a candidate for one of the two undergraduate student positions on Governing Council, said that the university needs to work around this problem. “People say maintenance isn’t sexy, and is therefore hard to fund,” he said. “Some of these repairs help U of T save energy, or could be tied in with renovations that make our spaces more innovative or allow us to expand hands-on research learning. If we sell maintenance on those benefits, it might be easier to get the province to cough up.”

UTSU president Munib Sajjad admitted that the union has not been active on the question of deferred maintenance. “However, we are a little disappointed in how U of T has been maintaining its own buildings,” he said. “We definitely think that the university is over-prioritizing expansion rather than maintaining its current quarters as well as its current students.”

Direct provincial funding for deferred maintenance through the Facilities Renewal Program (FRP) fell from a high of $4.7 million in 2010. The university anticipates receiving $3.2 million for 2013–2014. Swail said the university has shown a significant financial commitment to dealing with the issue. “Over time it inversed quite quickly — our internal funding eclipsed what the province was giving us,” he explained.

The university provided $13.1 million in internal funding for 2013, and that number is expected to grow by $1 million this year, to $14.1 million. Added to the anticipated $3.2 million fro the FRP, the anticipated total deferred maintenance budget is $17.3 million. Swail’s report suggests that maintaining the current condition of U of T’s buildings will require a yearly investment of $19.3 million.

In an October interview with The Varsity, Ontario’s Minister of Training, Colleges and Universities Brad Duguid said that universities need to take responsibility for the upkeep of their own buildings: “If an institution doesn’t have the capability of maintaining a facility, they ought to not be applying for funding for us to build it.”

Sajjad called for the university to reconsider which capital projects it funds. “If there’s going to be enhancements to the learning, enhancements for expansion, I think that’s where the province comes in,” he said. “I think the university really needs to take steps and re-prioritize its own funds in maintaining its own buildings.”

Coleman, who attended the Business Board meeting, says the university needs to do a better job of caring for its facilities. “The leaders of our university need to step up — right now the long term plan is “Sit tight and hope for the best,’” he said. “I think that the students and faculty that work and learn in these buildings deserve better.”

Mainawati Rambali, one of the two student members of Business Board, attended the meeting but did not respond to a request for comment. Andrew Girgis, the other student member, was not present on January 27 and also failed to respond.

The provincial Liberal government will draw up its 2014 budget in the coming months. Duguid said that new funding for capital projects is unlikely to be included in the budget.