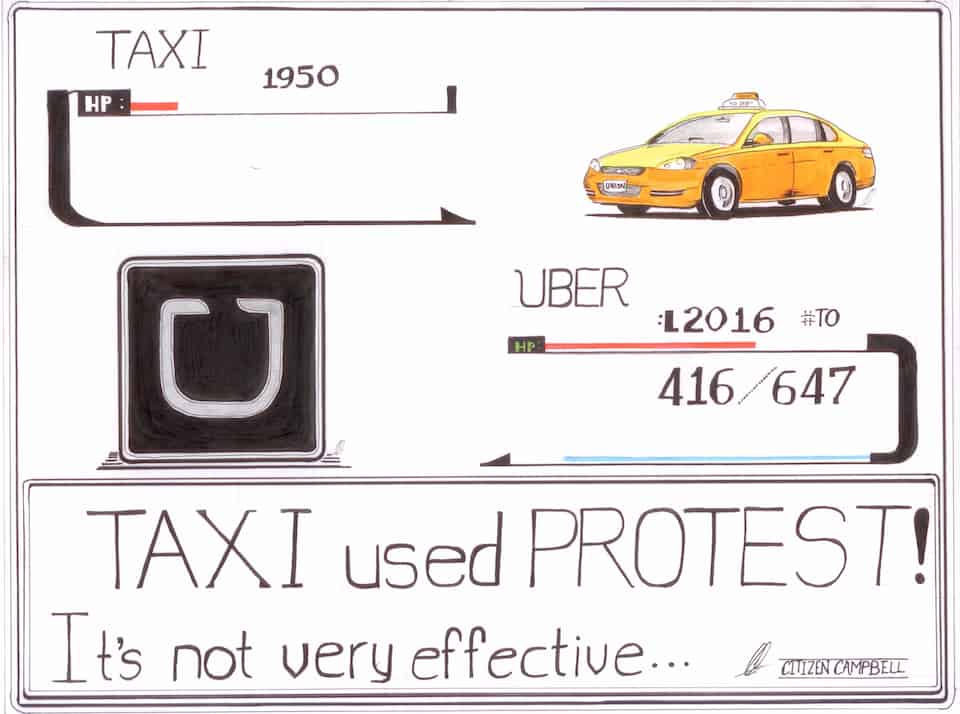

[dropcap]U[/dropcap]nless you have been living in a subway station, devoid of cell reception and therefore cut off from information about the world above, you will know that Uber has blown into Toronto with more bluster than last year’s polar vortex. Enraged taxi drivers block off downtown streets in protest, and have gone so far as to compare the company to ISIS. The taxi driver’s animosity to Uber, however, is misdirected. Beyond providing a better service, Uber has also exposed an archaic and corrupt taxi industry that, until the new platform arrived, Toronto didn’t know existed.

Uber arrived in Toronto in 2012 on the back of increasing notoreity. Rather than stand up to the company and its legions of online supporters, the city decided to let it operate while it consulted stakeholders and drafted up regulations surrounding

ride-sharing.

For over 50 years, the taxicab industry had operated as a cartel. In order to operate a taxicab, one must be in a possession of a license, known as a plate. Initially, the concept was fairly simple: the city would regulate the number of plates in accordance with supply and demand. With increasing demand, the number of taxis increased, and so did the number of plates that were issued. It did not take long for some enterprising fellows to realize, however, that plates could be turned into an investment.

As plate ownership increased, political pressure to restrict the quantity of plates grew, and their value skyrocketed. In 2012, a Toronto taxi plate was worth $360,000. In New York, over one million dollars. What resulted was a pseudo-feudal system. Plates have to be registered to certain cars, so plate owners devised ways of forcing drivers to pay exorbitant rates to lease the entity necessary to generate income as a taxi driver, thereby evading city regulators.

Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp, the co-founders of Uber, recognized the gap created by the taxi industry, and exploited it. Uber has made it clear that they are not a taxi company, and so should not be treated as such. Rather, they provide a service that connects riders to drivers. The app is nothing more than a glorified Craigslist, and their business model is not much different from a middle school student putting up posters in their former elementary school, advertising tutoring and babysitting services. By leveraging modern technology, they just found a more effective way of doing it.

The taxi industry’s argument is that Uber drivers are operating as unlicensed taxis, which purportedly raises a number of concerns surrounding insurance and passenger safety. What it really amounts to, however, is that for the first time, one of the most corrupt and protected industry in the city is finally facing competition. For a long time, taxi drivers’ greatest asset was their anonymity. Forget something in the back seat? Get over-charged? Good luck. Have trouble hailing a taxi? That’s because there aren’t enough. Operating as an exclusive service only serves to aggravate these conditions.

Uber cut straight through all those problems. All Uber drivers must undergo background checks and vehicle inspections before gaining access to the service. Uber users know the identity of their driver, and are encouraged to rate their experience afterwards. A low rating reduces the likelihood of getting further pickups, so Uber drivers have an incentive to provide good service. The elimination of rider-driver transactions means there is no risk of drivers swiping users’ financial information.

Uber also employs surge pricing, so rates go up when drivers are in high demand, which incentivizes more drivers to become ‘available’ during peak periods. The taxi industry’s purported concerns therefore amount to naught. Rather than operate according to market principles, they manipulated the civic government for their private benefit. The emergence of Uber has demonstrated that there is, instead, a better way of doing business.

Toronto should do all it can to encourage economic innovation. The reality our generation faces is that the traditionally rigid employment structure is eroding, and firms like Uber are ever more important sources of income. In an era of stagnating median income growth, the Uber business model provides huge benefits to those with flexible work schedules, including students. In the United States, 60 per cent of Uber drivers already have a full- or part-time job, 19 per cent are between 18 and 29 years old, and half of all drivers work less than ten hours per week.

If Uber continues to grow, the value of plates will decline to the point where drivers will be able to purchase a ride-sharing permit for a similar value. Hopefully, it will also decrease the barrier to entry in the taxi industry, which remains vital to many unskilled immigrants needing a reliable source of income.

Until that happens, the hostility between the taxi industry and Uber is likely to continue. As students, it is important that we remain open to alternatives and question the status quo. Uber’s corporate citizenship record is far from perfect, but any company that increases customer service standards, and fosters innovation and competition, should be lauded.

Jonathan Wilkinson is a fourth-year student at University College studying international relations.