For many of us, recalling our first days at the university can be quite an uncanny experience. I remember craning my neck to look up at the King’s College Circle arch for the first time and feeling as if there wasn’t a more perfect place in the world for me to pursue my education.

It is only over time that the cracks in the ‘perfect’ mould become more evident. After having experienced both the ups and the downs that the university has to offer, we come to appreciate its successes while nevertheless acknowledging the fact that it is far from flawless.

In these spirits, I’ve asked four contributors to weigh in on the areas at the university that are in the most dire need of fixing.

–Teodora Pasca, Comment Editor

Scheduling nightmares

Though the horrors of course selection are now safely behind us, U of T must improve on its system of course enrollment in the years to come. Our current system unfairly advantages those in upper years of study. It may be that enrollment must be staggered for reasons as practical as avoiding a system crash, but the impact of priority enrollment is disproportionate.

It’s not uncommon to hear stories of students who are unable to enroll in courses required for their program of study (POSt), simply because of the priority afforded to upper-year students in course selection. It is nonsensical that upper years are able to gain access to first-year courses, weeks before first year students themselves. In effect, it removes the meaning of designating courses as “100-level.”

A complete overhaul of the course selection system may not be necessary, but U of T must attempt to relieve some of its effects, including limited course availability. Usually, when a product is in high demand, shortages occur. U of T attempts to avoid the problem of shortages by either overcrowding classes or severely limiting the space available, both of which are to the detriment of students.

Students should not have to worry about being able to enroll in courses that are required of them by the university’s rules. If U of T insists on making such rules, it may be time to bend them.

Reut Cohen is a second-year student at Trinity College studying International Relations.

A one-dimensional education

Given that U of T is one of the top higher-education institutions in Canada, I was somewhat taken aback by the lack of variety in courses in my first year. The Eurocentric nature of the humanities and social sciences courses offered to students is a problem that is immediately evident in course listings across disciplines.

In Political Science or History, for example, the majority of the courses offered focus on Europe or North America from a European perspective. This is understandable, given that both continents have made a significant contribution to international affairs, but there are only so many different angles from which a student can analyze the fall of Napoleon Bonaparte.

There are countless English courses at U of T dedicated to European and North American authors — the department even reserves a full-year course for Chaucer enthusiasts — but the university reduces the works of the entire African continent into a single half-year African Lit course. The Literary Tradition course, an introductory English class, is dominated by European writers, despite claiming to be an “introduction to major authors, ideas, and texts.” Last year, the few non-European or North American texts included in the course were the Qur’an and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart.

Throwing in a book by a Nigerian author in an otherwise Western-dominated English course or speaking briefly about the Haitian Revolution in a course on French history is not enough. It is unfair not only to the students who do not see works from their cultures represented in their education, but to all students who desire a well-rounded education. Works by non-Western academics and cultures provide the exposure to different modes of thought that is very useful in dispelling racist notions placed on non-Western cultures by Western society. The university should be making an effort to hire academics who teach diverse topics, and professors teaching overview and introductory courses should strive to live up to those categories.

Saambavi Mano is a third-year student at Victoria College studying Peace, Conflict, and Justice Studies.

Barriers to mental health support

While some may find U of T provides an atmosphere that enables them to reach their full potential, others will face several difficulties and may need support. The U of T administration, faculty, and staff must continue to honour their commitment to student mental health, as reflected in the Report of the Provostial Advisory Committee on Student Mental Health, released in 2014.

In regards to progress of mental health issues, initiatives to implement mental health education for staff and faculty and assessments of the effectiveness of existing treatment programs are an excellent start. However, it is necessary for the administration to do more by implementing a communication strategy in collaboration with colleges and professional faculties. Effective promotion of mental health resources would ensure that incoming students are informed of programs and services available, and that they are also taught how and when to access them.

Although some colleges and faculties, as well as orientation committees, have introduced programs that highlight the mental health resources available to incoming students during orientation week, not all students partake in orientation. As a result, not all students are adequately connected to mental health resources at the time they arrive at U of T.

A communication strategy could take the form of year-round programming that seeks to educate students, as well as the distribution of educational material through print and electronic media. Raising continuous awareness ensures that students gain access to the resources available and increases the likelihood of a truly fulfilling university experience.

Andy Edem Afenu is a fifth-year student at New College studying Biochemistry and Health & Disease.

Action over reaction

In general, the university must be more proactive in its operations and actions. Much of U of T’s time, effort, energy, and resources are put into issues created by a lack of foresight or consideration of future students and faculty.

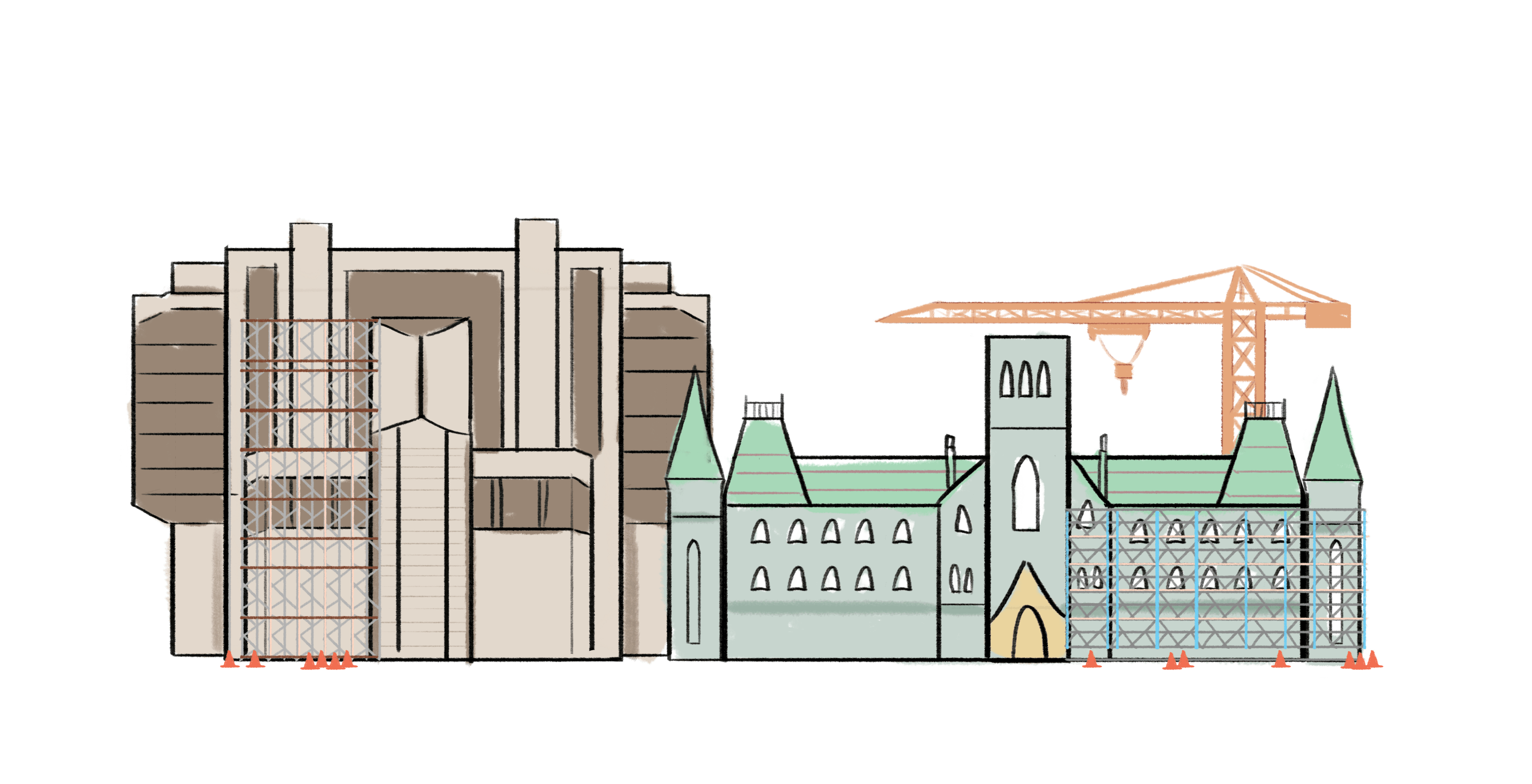

In terms of infrastructure, the staggering amount of deferred maintenance on campus has been documented; by trying to play catch-up with these outdated needs, the university is not only paying more to make these repairs, but also limiting itself in its ability to improve other spaces. The university should be staying on top of renovations and structural maintenance in the first place, in order to focus on tailoring spaces to the needs of students and faculty and making these spaces more accessible for all to use.

The situation is similar in regard to academics, as many courses and programs adopt a predominantly historical approach to subjects. While a background in history is important in understanding the current state of a topic, in today’s job market, it is ultimately a student’s adaptability that will contribute to their success. Given rapid rates of societal change, it may be difficult for professors to keep their teaching material up to date, but there is little point in pursuing an education that is not tailored to what comes after graduation. By being encouraged to look forward, students gain skills that are critical to their future success.

Elspeth Arbow is a fourth-year student at Innis College studying Buddhism, Psychology, and Mental Health Studies, and Cinema Studies. She is the Executive Vice-President of the Innis College Student Society.