What makes Lawren Harris’ iconic paintings ‘Canadian’? It could be his ethereal depictions of Lake Superior — masterpieces of high modernism — that adorn crowded galleries, inspire glossy postcards, and grace well-appointed living rooms across the nation. But are they ours?

This question surrounds The Idea of North: The Paintings of Lawren Harris, the Art Gallery of Ontario’s (AGO) latest exhibition of the artist’s paintings, which was curated by American entertainer Steve Martin alongside with Cynthia Burlingham, Deputy Director, Curatorial Affairs at the Hammer Museum, and Andrew Hunter, Fredrik S. Eaton Curator of Canadian Art at the AGO. The work of Harris, a Canadian national treasure, started its tour in the United States, where it is largely unknown.

The exhibition tracks the development of the artist’s style and subject matter, as it changed from urban landscapes to the sparse mountain vistas and the glaciers that he became renowned for. Harris’ early-period paintings of Toronto’s impoverished Ward neighbourhood are displayed alongside historical maps of the city, and his well-known Lake Superior paintings. The exhibition highlights Harris’ methodology and presents his work as part of Canada’s “cultural imagination.”

After producing sketches of various natural scenes across different time periods, Harris collated them on canvas to produce landscapes that captured the essence of regions but were not bound to a particular place or time.

As they alter between realist and dream-like, Harris’s paintings raise questions about Canadian identity; his work has become an opus dedicated to the North.

A divided Toronto

Harris’ early work shows the postwar-Toronto of the 1920s, a time of great inequality and social unrest. A scion of the wealthy Massey-Harris family of industrialists, Harris was born with the means to pursue art unfettered by financial restrictions. It was this awareness of his position of privilege that shaped the focus of his early subject matter: a struggling urban population beset by low wages and poverty so intolerable that it regularly provoked strikes.

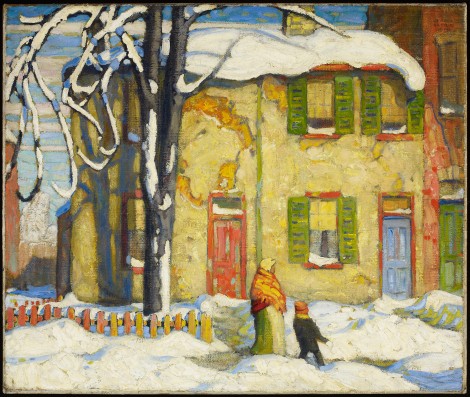

The first images of the exhibition depict the immigrants and working poor who lived in the hardscrabble conditions of the Ward. Beginning around 1900, Eastern Europeans immigrated to Toronto in record numbers, gravitating toward the Ward. At the time, the neighbourhood was comprised mostly of descendants of fugitive slaves and the children of immigrant railway workers.

The exhibition features paintings of residents wandering through mud streets lined with lean-tos and row houses crumbling under roofs of corrugated iron. Homes open out into squalid alleys, where porch doors with broken springs lie abandoned under a canopy of clotheslines hoisting drab sheets like sodden flags.

A display showing video footage of downtown Toronto around the time that Harris began painting the Ward accompanies the artwork. While watching a clip of a 1920s streetcar, I overhear a girl chuckling, “Probably the same one I took this morning.”

The images of the Ward show a walled-in slum, a sort of garrison situated steps away from what is now City Hall and Queen Street West. The Ward was a ghetto in the predominantly white Toronto of the 1920s. Urban renewal efforts only pushed residents into deeper isolation, as the Ward was gradually erased from view.

Into the wild

Harris saw economic injustice as a basic feature of capitalism. In the wake of World War I, his growing social consciousness was informed by the war’s devastation and its burden on the working poor. During wartime, many of these workers toiled in unregulated factories, while others fought on the front line, only to return to unexpected poverty, while their employers bathed in post-war prosperity.

Harris became interested in the spiritual movement of Theosophy while studying art in Europe, after being exposed to Eastern philosophy. Theosophy stresses the possibility of personal revelation through an intuition of God’s presence.

Driven by the bleak realities of the city and a growing spiritual and political consciousness, Harris sought refuge in nature.

Financing excursions to Lake Superior with artists who would eventually form the Group of Seven, Harris sought what the exhibition describes as a “distant and idealized nature that existed apart from the human condition.” In Lake Superior, he would find a “space of rich renewal,” according to Andrew Hunter, one of the curators.

Tree stumps bathed in luminescence, twisted strands of branches gesturing out toward clouds swollen with bright white light — these images rupture the air-conditioned sterility of the gallery with a surreal sense of motion and lucidity. From the iconic North Shore to the Lake Superior Hills, the landscapes breathe, ripple, and cascade with living energy.

The question of verisimilitude haunts their promise of transcendence. In the centre of the room is a glass case lined with sheets of brown paper, widely regarded as Harris’ best work. Working with a pencil, Harris sketched out crude skeletons of the landscape, transposing various drawings into one composite that would form the final painting.

Break from reality

The resulting image is not representative of any “real” place in the North. Rather, it is the reconstruction of multiple elements, filtered through the imagination of the painter. This raises a question: if his landscapes are the product of his consciousness, what, then qualifies it as Canadian?

Literary critic and University of Toronto academic Northrop Frye developed a conception of Canada’s relationship with the wilderness that helps to explain the appeal of Harris’ idealized representations of the North. For Frye, Canada was not a “frontier culture” like the Wild West of the United States, a distant zone that one entered to strike it rich or court death, or a place of promise and danger that one could visit and return from to the safety of their home. Frye claimed that for Canada, the culture was not one of frontiers, but garrisons.

The Canadian dependence on the fur trade meant settlements were organized around garrisons, fortresses that kept trappers warm during unfathomably cold winters. The harshness of the weather forced them indoors, safe from predators and the elements. Nature was kept at a distance.

Though the country was full of danger, it was also full of sublime beauty: the cascades of the Montmorenci and the tranquility of the St. Lawrence River, coaxing travellers deeper inward and swallowing them up like a whale; the awing heights of mountain rock and ice, sprawling like the sleeping giants of Ojibwe folklore. The landscape was so grand that it required a new poetry; the old Romantic model was better suited for the placid English lakes and gardens than the overwhelming darkness of the Canadian winter.

Harris’ paintings depict a landscape awesomely beautiful but hardly human. He was moved to re-envision the North because of the hardships he witnessed in the city. His diminished faith in human nature prompted an escapist sojourn into the frigid wilderness, where he could reconstruct nature as he saw fit, and create an interpretation of the Canadian North that is partly fantasy.

At the end of the exhibition, words are projected onto a wall underneath the title “Idea of North.” One note in a child’s handwriting reads: “Is that where Santa lives?”