“The Future of Canadian Mental Health,” hosted by the Hart House Debates & Dialogue Committee, focused on the shortcomings of the country’s mental health treatment options and the importance of viewing mental health the same way as physical health.

The January 15 panel featured prominent figures in the Canadian mental health scene.

Catherine Zahn, the President of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), noted that there have been great strides in opening up conversations around mental health. “In the past 10 years, we have seen this emergence of groups and individuals feeling confident to actually speak, themselves, about their own experiences.”

She broadly lauded the shift in mental health initiatives in bringing the conversation to children and youth and widening services available to young people in Canada. Still, Zahn argued that there remain obstacles to universal access to mental health services.

Intersectionality was another important point of discussion for the panel. Carol Hopkins, Executive Director of the Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, a health organization that focuses on First Nations and Inuit peoples, said that treating mental illnesses varies across cultures. As someone who worked for over 20 years in the field of Indigenous mental health, she explained that this variation is partially due to how people from different cultures feel a sense of belonging in different ways.

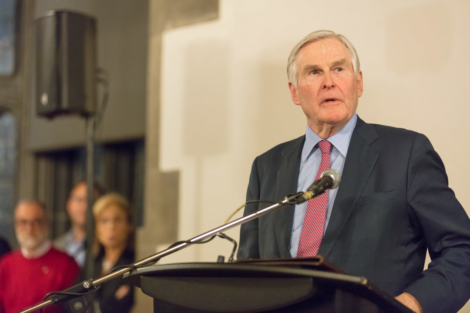

Michael Wilson, Chancellor of U of T. PHOTOS BY NATHAN CHAN, COURTESY OF HART HOUSE DEBATES AND DIALOGUE COMMITEE

Hopkins said that renewed conversations about reconciliation with Indigenous communities is beginning to make a difference in terms of resources available for treatment. “We didn’t have any investments on reserve for mental health services until we started talking about reconciliation.” She highlighted the importance of focusing on Indigenous communities, citing the high suicide rates among Indigenous populations.

Another speaker at the event was David Wiljer, a member of the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, a U of T organization that brings together people in the health industry. Wiljer raised a number of points about the double-edged relationship between technology and mental health.

He said that technology and the ways in which it is used can negatively affect mental health. However, he added that “technology used in certain ways might be able to break down some of the isolation that people are feeling and actually help improve access.” He noted social media campaigns’ ability to spread awareness about mental health issues and improve people’s understanding of how to access services.

Louise Bradley, President of the Mental Health Commission of Canada, said that mental health initiatives in universities were lagging behind initiatives happening in the workplace. She also added to Wiljer’s comments about technology, saying that it can help reduce wait times for people to receive mental health services.

Carol Hopkins, Executive Director of the Thunderbird Partnership Foundation.

PHOTOS BY NATHAN CHAN, COURTESY OF HART HOUSE DEBATES AND

Bradley said that in forming mental health initiatives in university, it’s crucial to think of all members of the community, not just students. “I think that’s not just looking at the mental health of students, although that’s extremely important, it has to go to faculty because the faculty and university staff aren’t paying attention to their mental health.”

The speakers repeatedly spoke about how many people still do not have access to what should be universal mental health care. Dr. David Goldbloom, Professor of Psychiatry at U of T, said that living in a rural area makes it much more difficult to obtain mental health services.

“There are barriers of language, or culture, of poverty, of housing that deprive people from accessing the services that are on paper, universal healthcare services,” said Goldbloom. “But they are not universal.”