In response to an independent U of T report that found that the university’s asbestos management practices meet legislated provincial requirements, and are even “more restrictive in some places,” labour organizations are criticizing the university over its perceived “inaction and inadequate response.”

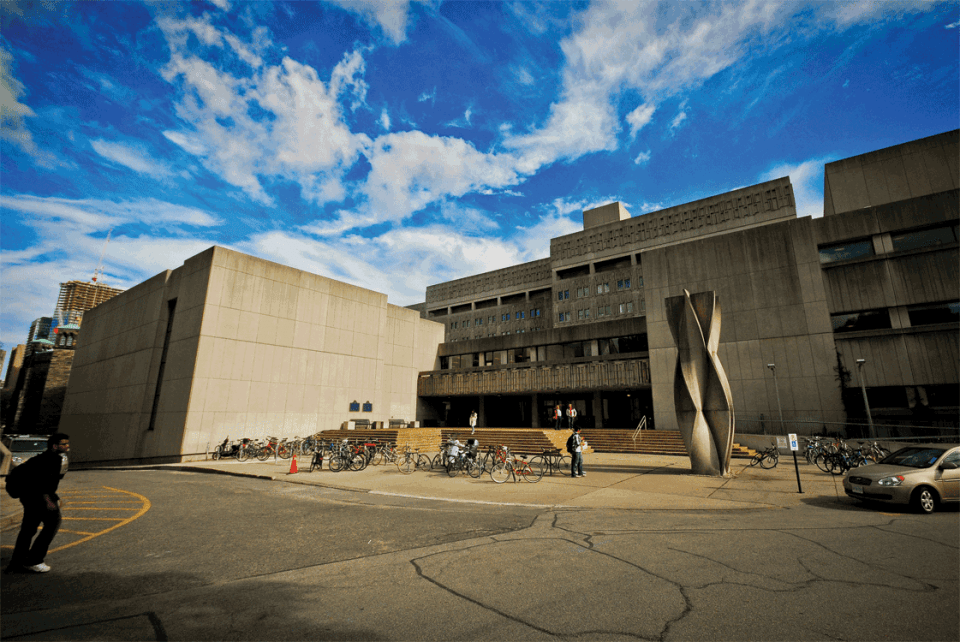

The report and the university administration’s response were made public on March 26, two years after asbestos-containing dust forced the closure of sections of the Medical Sciences Building.

The report is a product of an independent panel whose membership was finalized by U of T in January 2018. Submitted to the school in February, the report includes data from over 4,000 air samples taken from university buildings.

The samples found that 95 per cent of indoor air samples from the Medical Sciences Building are indistinguishable from outside air and have asbestos levels below existing standards.

However, the University of Toronto Faculty Association (UTFA), which represents U of T faculty, librarians, and research associates, has strongly criticized the university’s asbestos management and the report’s limited scope.

On April 18, the UTFA, the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) 3902, and the United Steelworkers (USW) 1998 held a press conference to voice concerns about the report and the university’s handling of asbestos.

CUPE 3902 represents contract academic workers at U of T, including teaching assistants and exam invigilators. USW 1998 represents U of T’s clerical and professional employees.

Setting standards

Asbestos is a silicate mineral that was commonly used in construction for insulation and fireproofing before 1990. It was later banned, with some exemptions, in Canada in 2018.

When asbestos fibres are released into the air, such as during maintenance or construction, they pose a serious health risk if inhaled.

Across Canada, the occupational exposure limit (OEL) — which is the standard acceptable exposure for construction workers — is 0.1 fibres per cubic centimetre (f/cc) for asbestos.

The generally accepted exposure standard for the general public is half of the OEL — U of T has set its campuses’ action limit to this 0.05 f/cc standard.

The report was unable to find a legally enforceable maximum or best practice standard for public exposure to asbestos, meaning that its findings are tied to existing best practices.

Vice-President Operations and Real Estate Partnerships Scott Mabury stood by the university’s use of a 0.05 f/cc action limit, adding that if it finds a standard that is “grounded in something that everybody can agree on… or is based on some physical reality, then [the university] will consider adopting that level.”

Although not legally enforceable, the Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change has set a desirable concentration of 0.04 f/cc.

Mabury, formerly the Chair of the Department of Chemistry, said that as an analytical chemist, it is “very difficult to tell the difference” between 0.04 and 0.05 f/cc.

U of T’s standards have been a point of contention. The report recommended that the university ensures that asbestos exposure is “as low as reasonably achievable,” with 0.02–0.04 f/cc as suggested reasonable guidelines. It added that 0.01 f/cc should be an aspirational limit.

Mabury, however, said that the university has yet to find a basis upon which to lower acceptable asbestos exposure levels.

Terezia Zoric, the Chair of the UTFA’s Grievance Committee, wrote to The Varsity that U of T must act on the report’s recommendations.

“Despite the Administration’s own Panel’s finding that it would be best practice for the Administration to adopt a more demanding standard for testing air quality, the Administration has shown a complete lack of willingness to do so,” she wrote.

“We are deeply disappointed that the Administration plans to use a less demanding standard and are concerned for the health and safety of UTFA members, students and staff.”

In response to UTFA’s critiques, Mabury told The Varsity, “We believe we will endeavour to always do the best we can. We are holding ourselves to a standard that is connected to a legal requirement because it’s something we can point to that is real and substantive.”

He added that the safety of the U of T community is the administration’s highest priority.

Administration and consultation

Another chief concern that the labour organizations have voiced is what they perceive as the panel’s lack of meaningful consultation with the U of T community.

The three-person expert panel was chaired by epidemiologist and l’Université de Montréal professor Jack Siemiatycki as well as Roland Hosein and Andrea Sass‐Kortsak, both associated with the Division of Occupational and Environmental Health at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health.

Jess Taylor, the Chair of CUPE 3902, said that the panel failed to listen to criticism and that outreach was “abysmal” and inaccessible, adding that unions were only provided a 10-day notice for the feedback sessions.

“There was a democratic deficiency of representation regarding the review panel process and implementation,” Taylor said. In response, Mabury told The Varsity that the panel “went well beyond what [U of T] asked them to do.”

He also said that the panel’s timing of the consultations was based on its members’ limited availabilities due to their “high demand on a global basis to provide [their] expertise.”

The UTFA has also expressed concern that the panel was not at arm’s-length from the U of T administration, “whose conduct should have been under scrutiny.”

Mabury, however, stressed that the panel was not influenced by the U of T administration.

“These were independent scientists. They are academics… These folks were chosen for their expert opinion. That’s what we asked for. That’s what we got,” he told The Varsity.

Among the recommendations of the panel was a re-evaluation of the university’s Environmental Health & Safety (EHS) Department’s organizational structure.

Under the current structure, Mabury is responsible for the removal of asbestos during capital projects, Vice-President Research and Innovation Vivek Goel is responsible for broad environmental health and safety, while Vice-President Human Resources & Equity Kelly Hannah-Moffat is responsible for worker health.

“We believe that separation of oversight duties has an internal value in having internal checks and balances that wouldn’t be there if we coalesced everything into one portfolio,” Mabury said.

While asbestos management practices will not change, the university will more explicitly articulate each Vice-President’s roles and responsibilities in its asbestos management practices.

Evaluating experts’ expertise

Beyond the lack of community input, Zoric told The Varsity that the UTFA believes that the panel should have included more experts, and ones with different areas of expertise, as its three members did not have “practical experience in asbestos abatement and management, and did not include representatives from employee groups working in affected buildings.”

Mabury said that the three members were chosen because most peer reviews involve two to three experts. He added that they were “the best from amongst those nominated” from an open nomination period, citing Siemiatycki’s four decades of experience as a researcher.

The UTFA retained the services of Environmental Consulting Occupational Health (ECOH), an environmental consultant, soon after the 2017 incidents. According to Zoric, ECOH advised that the university’s current standards are not appropriate and do not meet the best practice standard that the report calls for.