If you’re the child of immigrants, you may have endured a ‘lunchbox moment’ at school, when you would open your lunchbox in the cafeteria and other, whiter kids would judge the homemade meals your mom had made. You’d receive funny looks — maybe even an outright gag. They said your food was “weird” or “gross,” that it looked “like puke” or smelled “rotten.” And if lunch was a meal eaten with your hands, like roti and curry, you’d be stared at as an object of exotic fascination.

It didn’t matter that it was your favourite dish or that it carried your mom’s love, worked into the dough or stirred into the soup late the previous night. Your lunch was just too different. You were just too different.

The lunchbox moment is a real experience, and it’s common enough that people of colour can relate to each other through it. However, it never represents the full story of what food means to many racialized people.

In an essay for Eater, food writer Jaya Saxena brilliantly exposes how the trope flattens the experiences of racialized students. It emphasizes a desire for whiteness over any more positive or nuanced emotions racialized people may experience as they interact with members of their own community.

Growing up as a brown, Muslim kid in Toronto, I wanted to be like the other kids. I was upset that my dad didn’t watch hockey like the other dads — that he didn’t even know the rules and had no knowledge of the sport to share with me. I was upset that I got lumped together with the only other Muslim kid in class, even though our parents came from different countries and spoke different languages. But the longing I felt never manifested in a lunchbox moment.

When discussions about racialized food experiences are framed around the lunchbox, they don’t actually serve us in the way we might wish. “The lunchbox moment doesn’t require the reader to think about how class, religion, or caste could all change an immigrant’s experience,” Saxena writes. “It doesn’t point out all the invisible ways immigrants and [racialized people] are made to feel unwelcome.”

It’s precisely this simplicity that makes the trope appealing to a white audience. It reduces our stories to a sense of loneliness, eliminating the complexity of the racism — and the complexity of the joy — that racialized people experience in relation to food.

Food is about family

Sharon Liu, a fourth-year undergraduate at U of T studying East Asian studies, English, and creative writing, remembers experiencing her own lunchbox moments in middle school. Liu, who is Chinese-Canadian, grew up in Brampton, Ontario and frequently took leftovers from dinner to school for lunch the next day.

Liu remembers her classmates staring at the food she had brought. One boy asked her if she was eating cat or dog meat. She expected some kind of support from her teacher, but none came. So she put her food away, uneaten.

Still, making the lunchbox moment a universal shorthand for the experience of racialized people effectively ends the story of our childhoods with a painful moment. People of colour who’ve experienced lunchbox moments in childhood aren’t defined by them. They can come to celebrate and share their food later in life, in order to fully understand and embrace the otherness that inflicted them as children.

Liu certainly has. She remembers asking her mother for different lunches, especially Lunchables, because she wanted to fit in. But looking back, she finds that yearning somewhat ridiculous — the food her mother made “had flavour, for one thing,” and Lunchables are just indisputably bad.

“Looking [back], Lunchables kind of suck,” Liu says. “It’s just like, worse charcuterie.”

Liu has since spoken to her mother about those conversations and apologized for them. “She was hurt a little bit. She thought that I didn’t like her food, which is just the complete opposite [of how I feel] because my mom’s the best cook I know.”

Today, when Liu goes home, food is a family affair. Her mother would always try to make hui guo rou, also known as Sichuan-style twice-cooked pork belly — one of her favourite dishes since childhood. Her father would leave work early to buy the best quality pork belly. Then her mother would take up the laborious cooking process, which involves boiling the meat till tender, searing it, and finally stir-frying it in classic Sichuan flavours of chilli and fermented black beans.

Liu witnesses how taxing the cooking process is for her mother; “she’s sweating because [of] all the fumes, but she still does it every single time.” Making food for her daughter is an expression of love. Liu sees that more clearly now.

Marcelo Rosero, the owner of La Morena, holds a tray of fried empanadas. TAHMEED SHAFIQ/THE VARSITY

Food is about sharing one’s culture

Beyond school lunches and family dinners, food is often the best way to share one’s culture with the broader society. No one does that better than families who run restaurants.

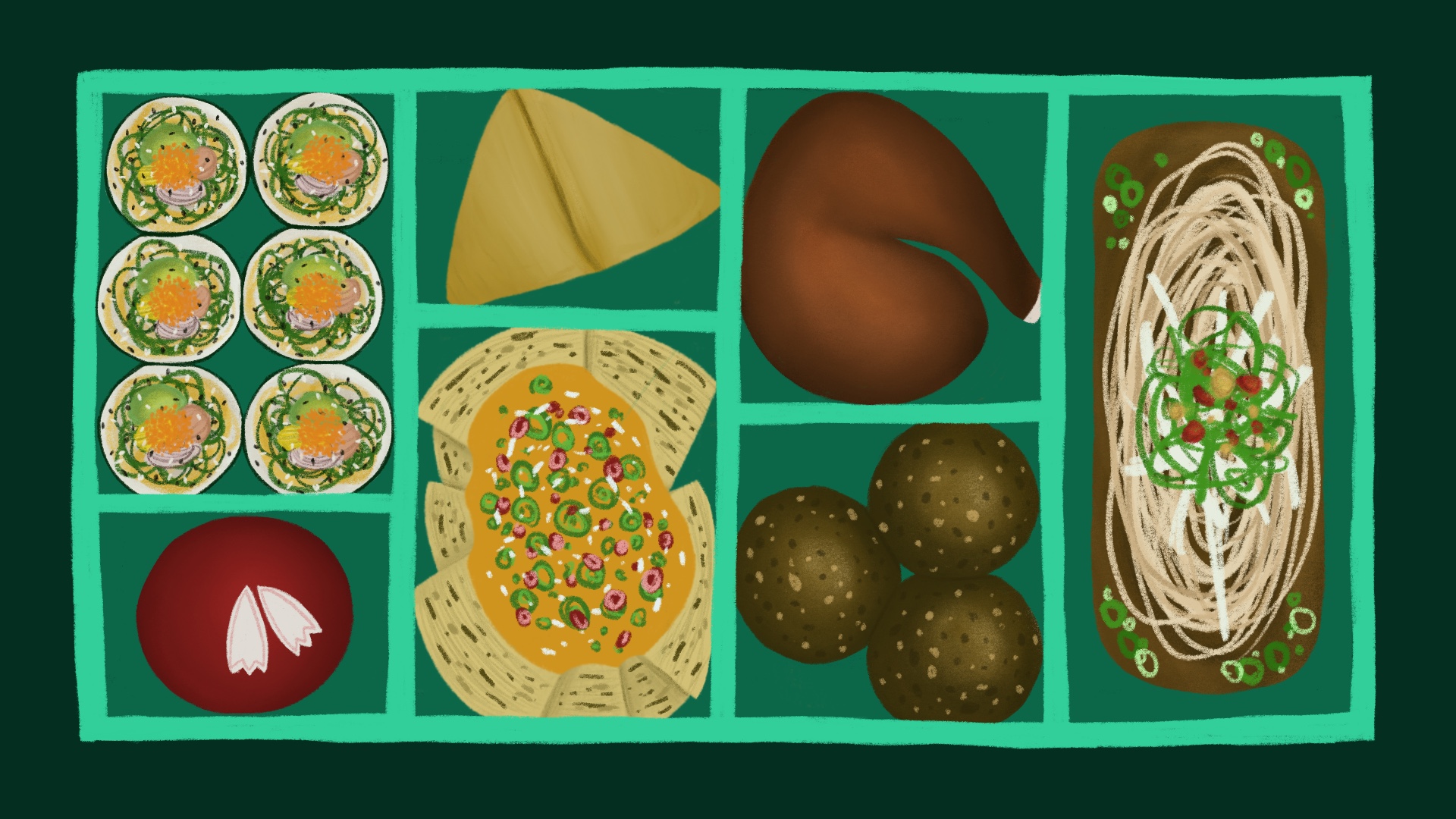

This is certainly the case at La Morena, a family-owned Ecuadorian café on St. Clair Avenue West in Toronto. The café is operated by Marcelo Rosero, a restaurant veteran of over 40 years; his ex-wife, Graciele Riofrio; and their children. Patrons can enjoy a variety of Ecuadorian classics, including empanadas, tamales, and ceviche.

In 1974, when Marcelo first came to Toronto to work in the restaurant industry, Ecuadorian cuisine was not well-represented in the city’s food scene. That is changing, but slowly.

“If you think [of] South American cuisine, you’ll probably [think of] Peruvian food or Colombian food. Ecuadorian food [is] not really well-established here,” says Andres Rosero, one of Marcelo’s sons who manages the storefront. “One customer that always comes by is like, ‘You guys have to make the birria tacos.’ We don’t do that.”

Birria tacos are a type of Mexican beef tacos that are served with soup. They’ve become wildly popular in the past couple of years, as photogenic videos of the tender beef being dipped into a spicy red consommé have been shared widely on TikTok and Instagram.

Andres’ anecdote is a perfect example of one complexity of immigrant food cultures: sometimes certain foods become stand-ins for an entire region’s culture, especially when they are swept up in social media trends.

Marcelo insists that Ecuadorian food is unique, and he wants his customers to appreciate it that way. For example, he says that Ecuadorian food is less spicy than Mexican food because, in Ecuadorian cuisine, spicy sauces are served on the side.

All of La Morena’s recipes are family-owned. TAHMEED SHAFIQ/THE VARSITY

There are some parts of La Morena’s menu that would be recognizable to people who aren’t familiar with Ecuadorian food. For one thing, they serve their own versions of the fresh fruit juices you can often find at Mexican restaurants, including lulo juice. Lulo is a small citrus fruit that only grows in Central and South America, with a taste halfway between passionfruit and orange. Of course, they also cook some uniquely Ecuadorian dishes like humitas, steamed bundles of corn flour and cheese that resemble a tamale, but taste sweeter.

But the café’s signature items are their empanadas, which come in three flavors. Each one uses a different type of casing, made with wheat flour, rice flour, or morocho, which is a kind of corn flour made from a maize cultivar grown in Argentina and Ecuador. I found the fried cheese empanadas the most delicious: light and filled with warm, melted cheese and served — if you ask — with a sprinkling of sugar in the traditional Ecuadorian way.

All recipes are family-owned, reflecting Marcelo’s desire to showcase the way his family does Ecuadorian food. “I wanna be firm in my flavours,” he says.

Andres hopes more people will warm to Ecuadorian food over time. “Just being in Toronto, we have such easy access to so many cultures. I think everyone should be open to trying new foods… because you never know what you might be into.”

Food is a journey

It’s true that food presents an opportunity for racialized people to celebrate their culture and communities, but not everyone grows up with a strong connection to their cultural food. Sometimes, it takes time, new experiences, and the right company for that connection to flourish.

At least, that was the case for Yasi Faubert, a third-year undergraduate studying immunology, bioethics, and health and disease. Faubert and his younger sister were both adopted from China and raised in Windsor, Ontario by two white parents. He describes the neighbourhood they grew up in as “very white”— apart from him and his sister, there was only one other Chinese kid at their school. “The closest you could get to quote unquote ‘ethnic food’ was the one Italian restaurant in the whole town,” Faubert recalls.

As a result, his childhood experiences of Chinese food revolved around the ‘Westernized’ Chinese food that was available. Because his mother was often too busy with work to cook, his school meals were often Lunchables.

In his early teen years, though, he took a trip to Toronto that began to change his perception of Chinese food. His mother took him and his sister to Pacific Mall, a large Asian shopping mall in Markham. It was the first time he had ever seen so many Asian people. “We had really good Chinese food,” Faubert says. “It felt… more genuine, being surrounded by so many people who looked like me.”

Later, in high school, Faubert got a job as a dishwasher at a Cantonese restaurant. The staff spoke to each other in Cantonese, which he couldn’t understand. “Once in a while, they’d snap their fingers at me to get my attention and say, ‘You got to do this,’ or ‘You got to do that.’ ”

But the staff also wouldn’t let Faubert go unfed. If he hadn’t eaten all day, they would give him a meal to take home. Having come from a family where his parents’ schedules meant sit-down family dinners were uncommon, Faubert found their unexpected kindness deeply touching. He felt a sense of a shared identity with his co-workers — an experience of connection and culture that was new to him.

Now, Faubert lives with two roommates who both love to cook. One of them is also from a Chinese background. Going grocery shopping together and cooking with them has brought Faubert into closer contact with Chinese culture; now, he has someone to coach him through the names of unfamiliar ingredients or explain the significance of unfamiliar foods.

His confidence in the kitchen is also growing. Last year, he started cooking Asian dishes on his own. He started with tteokbokki — Korean rice cakes — before moving on to other dishes like mapo tofu and katsudon, or Japanese cutlets over rice. One day he made udon, and as he sat down with the bowl of brothy noodles he had made entirely by himself, a feeling of pride washed over him. “I was one step closer to being comfortable with the fact that I’m Chinese, and I can make food that tastes good.”

Today, many of his memories of cooking Chinese food are connected to pride. “It’s made me want to cook more,” he says.

Food is a problem

Faubert’s story is a heartwarming reminder of why food is central to our identities. And yet, if we end conversations about food on a uniquely happy note, we can fail to notice the racialized people who aren’t as fortunate — people whose experiences are shaped by larger, systemic forces of class and economic precarity.

The clearest food-related intersection between race and politics is food insecurity or the lack of stable access to healthy food. Unsurprisingly, one of the most common causes of food insecurity is a low income, but racialized people are also at a higher risk.

Statistics Canada’s 2017–2018 Canadian Community Health Survey identified that one in every eight households was food-insecure. PROOF, a U of T-based research group studying national food insecurity, found that those households were more likely to be racialized. 28.9 and 28.2 per cent of Black and Indigenous respondents, respectively, reported being food-insecure, compared to just 11.1 per cent of respondents who identified themselves as white.

“We consistently see that Black and Indigenous households are at greater risk of food insecurity, even after accounting for other sociodemographic factors,” wrote PROOF research coordinator Tim Li in an email to The Varsity.

Likewise, studies from 2011 and 2013 found that Latin American immigrants to Toronto who were food insecure had trouble accessing resources because of a language barrier. They had difficulty understanding food labels, communicating their needs with store clerks, and reading coupons that could have saved them money. They also lacked access to foods they were used to, and even when these foods were available, they had no idea where they could be found.

According to Ken MacDonald, a UTSC professor in the human geography department, part of the problem is that culturally relevant foods tend to be clustered in small neighborhoods. For racialized people without access to a car, that presents a challenge.

“You’re going to spend two hours on the bus to go and get stuff that you’re familiar with. You can take four hours out of your day [to go] once a week,” MacDonald explained.

MacDonald’s research has shown that this problem is a modern one. Before World War II, cities were responsible for creating spaces where people could access affordable food, so they built and maintained public markets for food purveyors. But, in the 1950s, supermarkets became more common. They were spaced farther apart because they were designed with car-owning customers in mind. It’s because of this change, MacDonald says, that public institutions came to think of providing food as the private sector’s responsibility, not their own.

MacDonald thinks we can solve food insecurity if we return to this model. He points to cities like Barcelona, where public markets still exist. To him, a growing city like Toronto can easily build more markets just by including them as part of current development plans. Governments can already require new property developments to provide some level of public service, like a green space or community centre. “Why not make a public market a condition of actually developing new space?” he asks.

The rush to build new condos when we can easily build new public markets is a failure of imagination. Ultimately, so much of the way we think about food is also a failure of imagination.

When we tell ourselves that food is just nutrition, we mask its political nature. When we construct simple narratives around food, we hide the complexity and fluidity of personal experience. And when we rely on the lunchbox moment to define racialized food experiences, we lose out on all the stories of joy and found family that food can create — overlooking the structural racism embedded in the urban landscape.

A lunchbox has multiple components. So do our stories.