Artists are often creatively motivated by the ontology of scientific questions. For example, while Einstein and his contemporaries were frustrated by the absurdity of discoveries in quantum physics — including the theories of wave-particle duality, quantum tunneling, and quantum indeterminacy — in the early 1900s, surrealist artists were undeniably excited by them.

What we know to be true of the macroscopic world mostly falls apart at the subatomic level. This presented a challenge for physicists who had to reassess the older theories that subatomic particles always exhibited particulate behavior. But this same strain of ambiguity inspired surrealist artists, who considered themselves to be explorers of unconventional and unknown realities.

Similarly, Drift: Art and Dark Matter, an art exhibition at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto curated by Sunny Kerr with assistance from Michelle Bunton, is another such collaboration between scientists and artists on dark matter.

Within the exhibition, astroparticle physics is extracted from its intimidating jargon and made romantic and philosophical through the works of Josèfa Ntjam, Jol Thoms, Nadia Lichtig, and Anne Riley. The Varsity spoke with some of the exhibition’s artists and scientists, as well as the exhibition’s curator about Drift, the artistic process, and the science behind it all.

Detecting dark matter

In an interview with The Varsity, Miriam Diamond, an astroparticle physics professor at U of T, posited that the universe is 25 per cent dark matter, 70 per cent dark energy, and five per cent ordinary matter — which makes up everything we see and touch. We can see ordinary matter because it interacts with photons — the carrier particles of light — and reflects light back into our eyes.

On the other hand, dark matter evades direct detection because it is made up of particles that do not interact with photons, making it invisible to human beings. Astrophysicists theorize that dark matter exists because dark matter’s gravitational pull and its effect on other atoms are observable.

Diamond added that scientists sometimes use vessels of liquid xenon or liquid argon to detect dark matter because they produce light when dark matter particles interact with them.

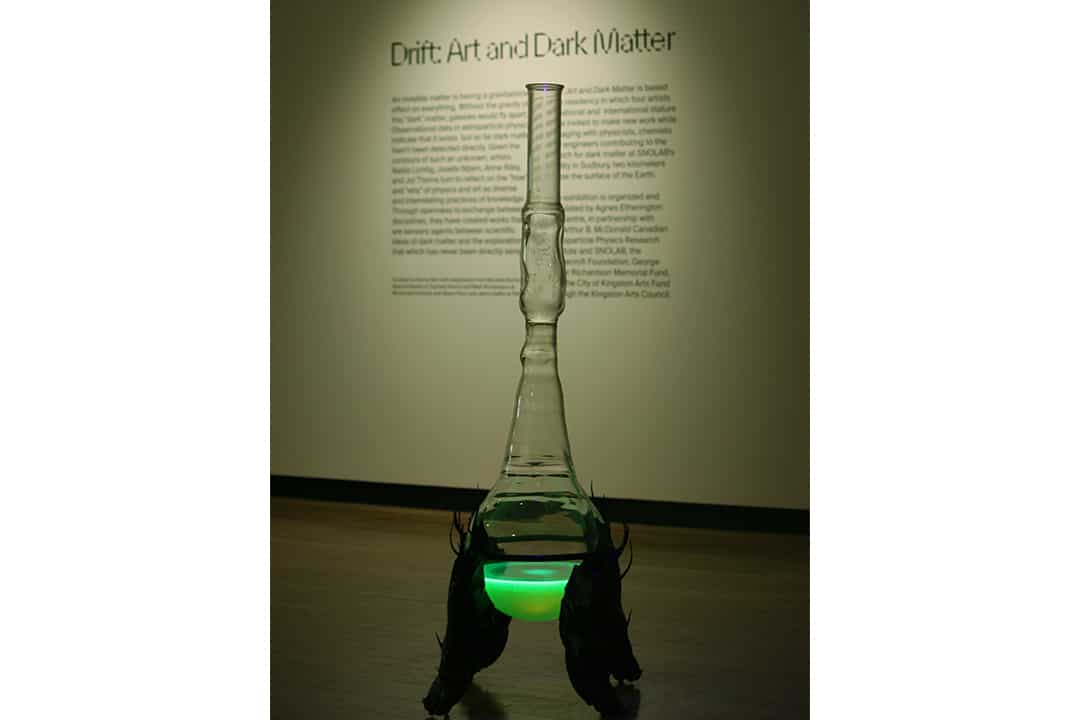

In Drift, Ntjam’s “Luciferin Drop,” a glass cauldron-like sculpture filled with green luminescent liquid, references this indirect detection of dark matter particles. “I love the juxtaposition of detecting dark matter, which does not directly interact with photons, through these light signatures,” Diamond said of the piece.

Flattening the multi-dimensional

Another work in the exhibition, Thoms’s “The Bulk: Frameworks,” was inspired by research on multi-dimensions. The two sculptures that form the piece are primarily made of steel, and they cast flattened shadows on the ground.

Jol Thoms’s The Bulk: Frameworks JOYCE SILVA DESMOND ; THE VARSITY

Aaron Vincent, a physics professor at Queen’s University, said in an interview with The Varsity that if there are multi-dimensions, we can only infer that they are there by observing their ‘shadows.’ I think that the shadows’ incompleteness lends them an allegorical richness.

“[The Bulk] creates a very good metaphor for both art and science,” Vincent said. “After completing some study, you’ve usually raised more questions than you’ve answered, and you’ve realized that your ignorance was actually a lot larger than you thought when you started.”

Thoms also created “n-Land: the holographic (principle),” which explores connections between the cosmos and the Earth.

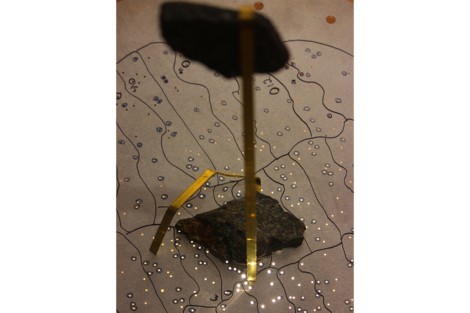

Jol Thoms’s Sudbury basin shatter cone rock sculpture JOYCE SILVA DESMOND ; THE VARSITY

In an interview with The Varsity, Thoms explained that the piece features one of the plates from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), called a plug plate. These plates are covered in drilled holes and over ten thousands of them are used over at SDSS to map the location of the stars in the sky.

“n-Land: the holographic (principle)” also incorporates a Sudbury basin “shatter cone” rock, which is a type of ‘sculpture’ that might form in the rock layer when a meteorite hits the Earth. When asked about the “shatter cone” rock, Thoms said, “[The meteorite’s] impact fractures the [Earth’s] mantle, and the minerals come up and solidify in the crust… and all the [formed shatter] cones point toward the centre of [that] impact.” Therefore, making the rocks an important landmark for a productive mining site.

I specifically appreciated how Thoms used Earth-sourced materials like steel, paper, and sand to demonstrate how scientists flatten, reduce, and digitize information to transcribe it into ordinary particles or a dimension we can understand. It’s an underlying paradox that threads together every piece in the exhibition.

Collapsing the epistemic divide

Meanwhile, the focus of Lichtig’s pieces is more abstract — they are not explicitly about dark matter or even cosmology. Instead, the process by which the pieces were made is connotative of the language and philosophy associated with dark matter.

One of her pieces, “Blank Spots,” is a series of frottages — a work created when a soft pencil is rubbed over a paper pressed to a textured material — that deconstruct the majestic nobility of the cosmos while mirroring how galaxies are scanned for dark matter. She does so by figuratively scanning the Earth for neglected matter or remaining traces of a traumatic history.

Nadia Lichtig’s Blank Spots JOYCE SILVA DESMOND; THE VARSITY

According to Thoms, the exhibition attempts “to displace epistemic hierarchies” by applying scientific vocabulary to works of art. This is similar to how Lichtig’s piece applies the technique of “scanning” to poor dust and dirt. Thoms added that his work aims to democratize science, allowing scientists to engage with storytelling that makes knowledge accessible. Drift displays the outcome of different epistemologies or different ways of probing knowledge, bleeding into each other.

The trade-off

The pieces in this exhibition accommodate a research-directed imagination to creatively respond to something that has never been directly detected by humans. It is precisely an absence of data on dark matter that becomes the precursor to creation.

Perhaps it is only in this elusive position between ignorance and confidence that we can revive some of our capacity for imagination. Knowing comes with a trade-off: we shed endless possibilities for a more concrete understanding of the universe. But when we are not yet restricted by the parameterized single perspective that knowing allows, we can create without bounds.

Drift: Art and Dark Matter carries this time-specific stamp of creativity that is endemic to a time before knowledge. When we eventually discover and become comfortable with axiomatized knowledge about dark matter, we will internalize it and, consequently, lose the capacity to recover the imagination predicated on our ignorance. So go visit Drift and enjoy the outcome of this imagination before it is compromised.