Sahir Dhalla: Ethics-specific courses provide unique perspectives

An understanding of ethics is vital when designing experiments that respect the rights and dignity of others. Without studying ethics, we risk experimenting with methods that exploit individuals and use them as simply a means to an end. It has been shown throughout history that a lack of appreciation for ethical guidelines results in violations of human rights. To see a lack of respect for human dignity, we only need to go back a few decades to see programs like the CIA’s MKUltra and more.

A reservation many might have with staying respectful of ethical principles is that it slows down the pursuit of knowledge in favour of arbitrary guidelines that are difficult to implement consistently. However, a better understanding of ethics can be more permissive than restrictive.

Take gene editing and cloning, for example. Much of the research in this area remained stagnant for decades, because ethical committees relied on “personal philosophy” and “gut feeling” when approving experiments. Better guidelines informed by ethical principles would eliminate these issues, creating well-based systems to guide our research.

Having designated ethics courses that science students must take might seem frustrating, but it is essential. We could explore ethical issues within a science course itself, but there are additional perspectives that philosophy courses explore better. Ethics as a field has distinct methodologies and perspectives. Students in the sciences must have a basic understanding of this area to inform their future research and evaluate their beliefs. Speaking from experience, courses like PHL275 — Introduction to Ethics allowed me to understand why I held some of the views I did, and allowed me to question my values.

The study of ethics is incredibly vital for science students, now more than ever.

Andrea Zhao: Integrate ethics rather than teaching it separately

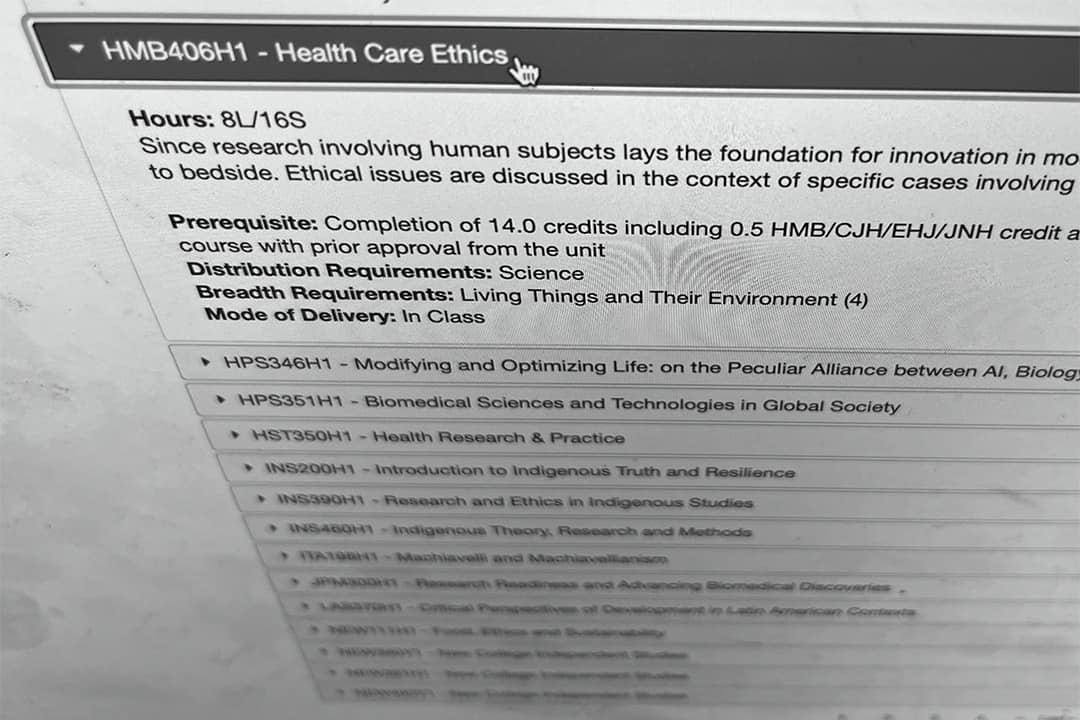

Ethics requirements for science students at U of T are inconsistent and do not ensure that all students will be educated in ethics during their time as undergraduates. As someone with a double major in immunology and molecular genetics, my personal experience with ethics at U of T has been extremely limited. Surprisingly enough, I am not required to take any ethics courses to complete my degree, despite the fact that many students in my field of study end up working in health care or a related research field, where ethics-related protocols and concerns will be relevant.

After completing half of my degree, I have yet to encounter a prolonged discussion about ethics in any of my courses. This is not to say that any of my instructors have been at fault — the study of ethics is simply not built into the curricula of most science courses. Those required to take ethics courses are expected to learn about the subject in those classes, whilst those taking degrees without the requirement are left to find their own way and may end up graduating without having encountered ethics at all.

The content of many ethics courses may not be easily applicable to policies and issues within the sciences. A class that fulfills the requirement for some science majors, such as PHL265 — Introduction to Political Philosophy, may be useful to someone taking a degree in social sciences, but is less applicable to STEM students. More specialized courses, like PHL281 — Bioethics, may present more relevant content for students in the life sciences, however.

Additionally, the ethics requirement is often limited to one course, or half a credit, over the course of an entire degree. It can be difficult for students to effectively apply the principles and concepts of ethics they learn in a classroom to their overall studies and future career if they only encounter those issues within the context of a single class over one semester.

That being said, the categorization of ethics and related practices as a course requirement rather than an integrated and lifelong set of considerations may actually diminish the importance of maintaining a good ethos. After graduation, many science students may find themselves working in industry or research. Whether they may be treating a patient or developing a new experiment, they must always do so in as responsible a manner as possible, whilst being wary of potential ethical dilemmas.

By incorporating discussions of ethics in a greater number of science classes and introducing concrete examples of ethical concerns in modern science, students will be more likely to understand the overarching importance of ethical practices in their education and careers. In fact, the study of ethics goes far beyond the classroom; hospitals, laboratories, and research programs taking on undergraduate volunteers and interns should make clear efforts to demonstrate good ethical practices in their day-to-day work to instill conscientious and sustainable habits into their students. Ethics and science go hand in hand, and the two should be taught as such.